In less than a month, rockets from Japan, India and China have all failed to reach their planned orbits, destroying navigation and Earth observation satellites that were supposed to guide traffic, support farming and improve disaster warnings. Japan’s H3 rocket lost the Michibiki No. 5 navigation satellite on December 22, India’s trusted PSLV failed on January 12 with 16 payloads on board, and on January 17 China saw both a Long March 3B and the private Ceres 2 rocket suffer anomalies in a single day.

On social media in China, commentators quickly nicknamed that Saturday of back‑to‑back failures “Black Saturday”. For the most part, coverage has focused on reliability and geopolitics. Yet for people who depend on a weather app to plan their workday or on accurate maps to move goods, the bigger story is environmental.

These mishaps remove satellites that watch Earth’s changing climate and push launch providers toward repeat flights that add more pollution and debris.

Lost satellites mean fewer eyes on a heating planet

Japan’s lost payload, officially called QZS 5 or Michibiki No. 5, was meant to strengthen the Quasi Zenith Satellite System, a regional navigation constellation that augments GPS over Japan and the wider Asia Pacific region.

QZSS improves positioning accuracy in dense cities and mountainous regions and also carries services under development for disaster alerts and crisis messaging, such as sending warnings directly to receivers when earthquakes or floods threaten. When a satellite like this fails to reach orbit, it does not only hurt national prestige. It delays upgrades to systems that keep evacuation routes clear and emergency crews where they need to be.

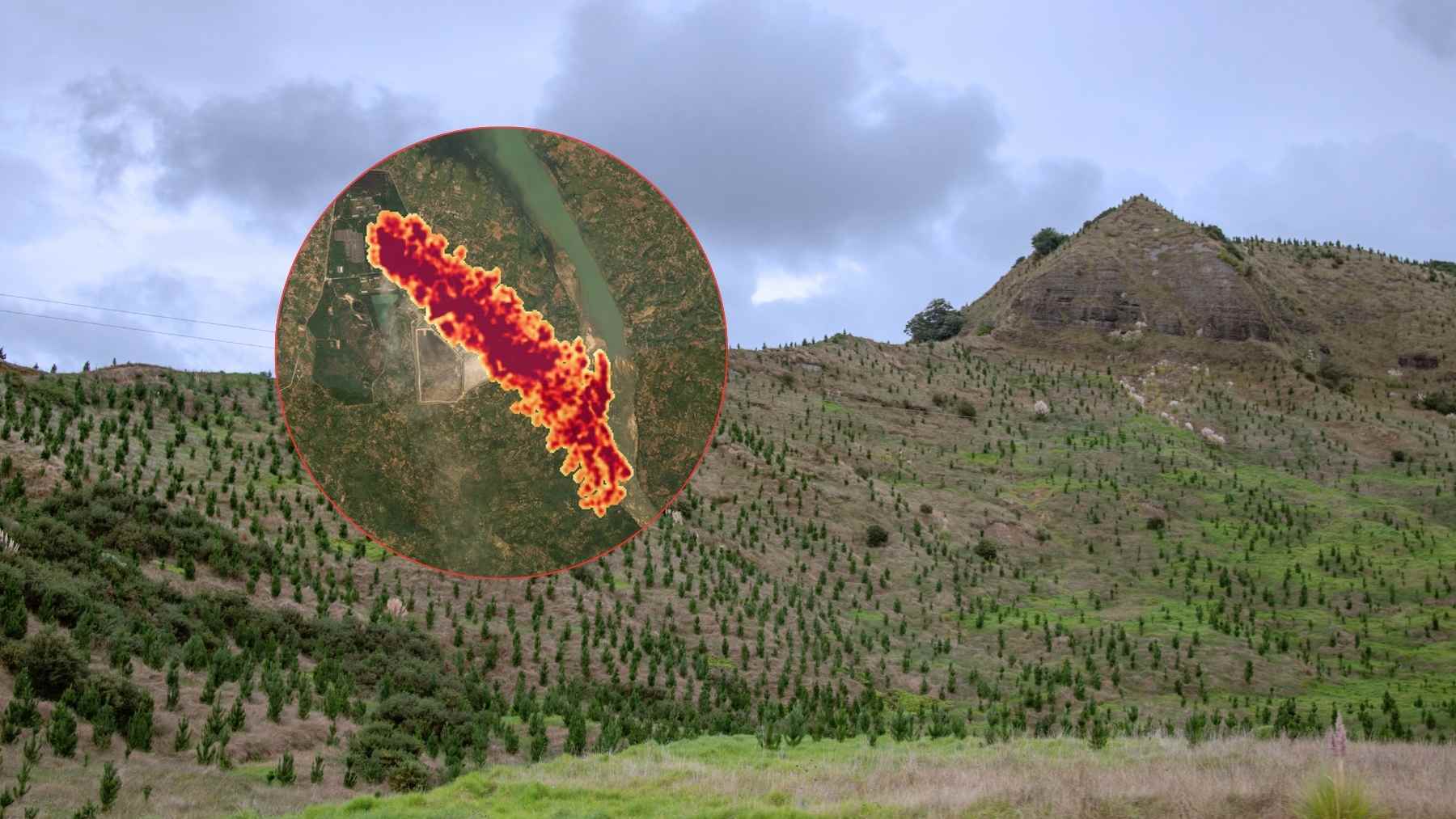

India’s failed PSLV C62 flight carried EOS N1, also known as Anvesha, a hyperspectral Earth observation mission designed to monitor crops, water resources, forests and natural disasters.

Hyperspectral sensors can pick up subtle changes in vegetation health, soil moisture or water quality, which help farmers fine tune irrigation and allow agencies to spot drought stress or pollution before it becomes visible to the naked eye. With that satellite now lost, planners will have to wait for a replacement before those data streams come online.

Even China’s Shijian 32 spacecraft, which state media simply describe as a test satellite, fits into this picture. The Shijian family often trial new technologies in orbit, from communications systems to techniques for handling debris. When those experiments fail, the knock‑on effect is slower progress toward safer, more sustainable operations in orbit.

More launches, more pollution above the clouds

Rocket launches are still a tiny slice of global carbon pollution. One analysis estimated that in 2018 all rocket flights together produced far less than one hundred thousandth of world carbon dioxide emissions, while aviation contributed about 2.4%. At first glance that sounds reassuring.

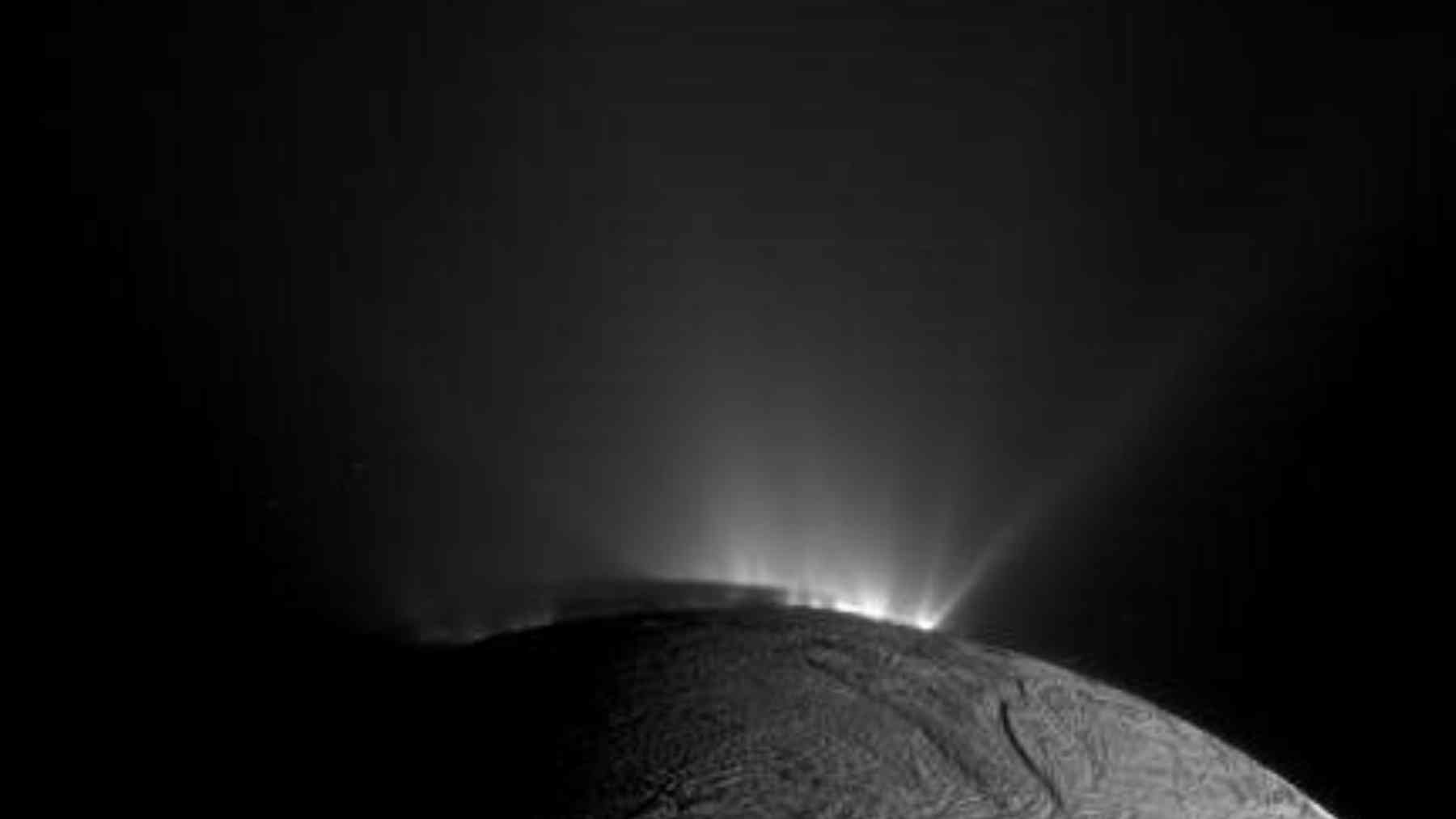

The trouble is that where emissions end up matters almost as much as how much we emit. A typical orbital launch can release on the order of a few hundred tonnes of carbon dioxide, along with soot, directly into the upper atmosphere. Studies by US and European researchers have found that black carbon particles from rockets accumulate high in the stratosphere, where they trap heat and may interfere with ozone recovery.

A recent team at University College London calculated that rocket launches in 2023 and 2024 burned more than 153 thousand tonnes of propellant and tripled emissions of climate altering soot and carbon dioxide compared with earlier years.

They also warned that soot at these altitudes can have up to 500 times more warming impact than an equivalent mass of particles released near the ground. Put simply, every failed launch that must be repeated adds a high impact plume of pollution to a layer of the atmosphere that is particularly sensitive.

Debris, oceans and fragile habitats

Launch failures and routine missions alike leave a footprint that extends far beyond the pad. Lower stages and fairings often fall into designated drop zones in the ocean. In rare cases entire rockets or upper stages come down in uncontrolled ways that worry coastal communities and airlines. Experts now warn that falling debris could pose a nontrivial risk to aircraft as launch and reentry rates keep rising, even if the absolute odds of a strike remain low for now.

Scientists are also starting to map how launch sites and drop zones overlap with biodiversity hotspots. A study published in 2024 found that more than 90% of global spaceports sit in regions where over half the habitat is unprotected and that more than 60% of operating sites are within or near protected areas, especially in tropical and subtropical forests. Another line of research suggests that space objects and debris increase the ecological footprint of human activity and contribute to long-term environmental pressure through both atmospheric and orbital pollution.

For coastal wildlife, repeated sonic booms, splashdowns and metal fragments landing on the seafloor may not make headlines, but they do add one more stress on ecosystems that already face warming waters and plastic pollution.

Turning failure into a greener reset

Asian space agencies are now combing through telemetry and hardware to work out what went wrong. Japan’s space agency JAXA has already pointed to damage in the H3 fairing separation system and fuel tubing that likely shut down the second stage early. India’s ISRO is analyzing repeated problems in the PSLV third stage, while China’s state contractor and private firm Galactic Energy both report ongoing investigations into their Long March and Ceres vehicles.

In parallel, an entire industry is emerging around launch failure analysis, with one market study projecting that dedicated services and tools for diagnosing rocket mishaps could grow to about $2.06 billion in annual value by 2030.

At the end of the day, what that sector chooses to prioritize will matter. If it focuses only on getting rockets back to orbit quickly, emissions and debris will keep mounting. If it also folds in environmental criteria, from cleaner propellants to better end-of-life disposal, every investigation could nudge the industry toward greener practices.

For most of us, satellites are invisible infrastructure. We simply expect our navigation apps to work and our flood alerts to arrive in time. The recent failures in Asia are a reminder that those services depend on a launch system that is growing fast and, to a large extent, still learning how to live within planetary limits.

The official statement was published by JAXA.