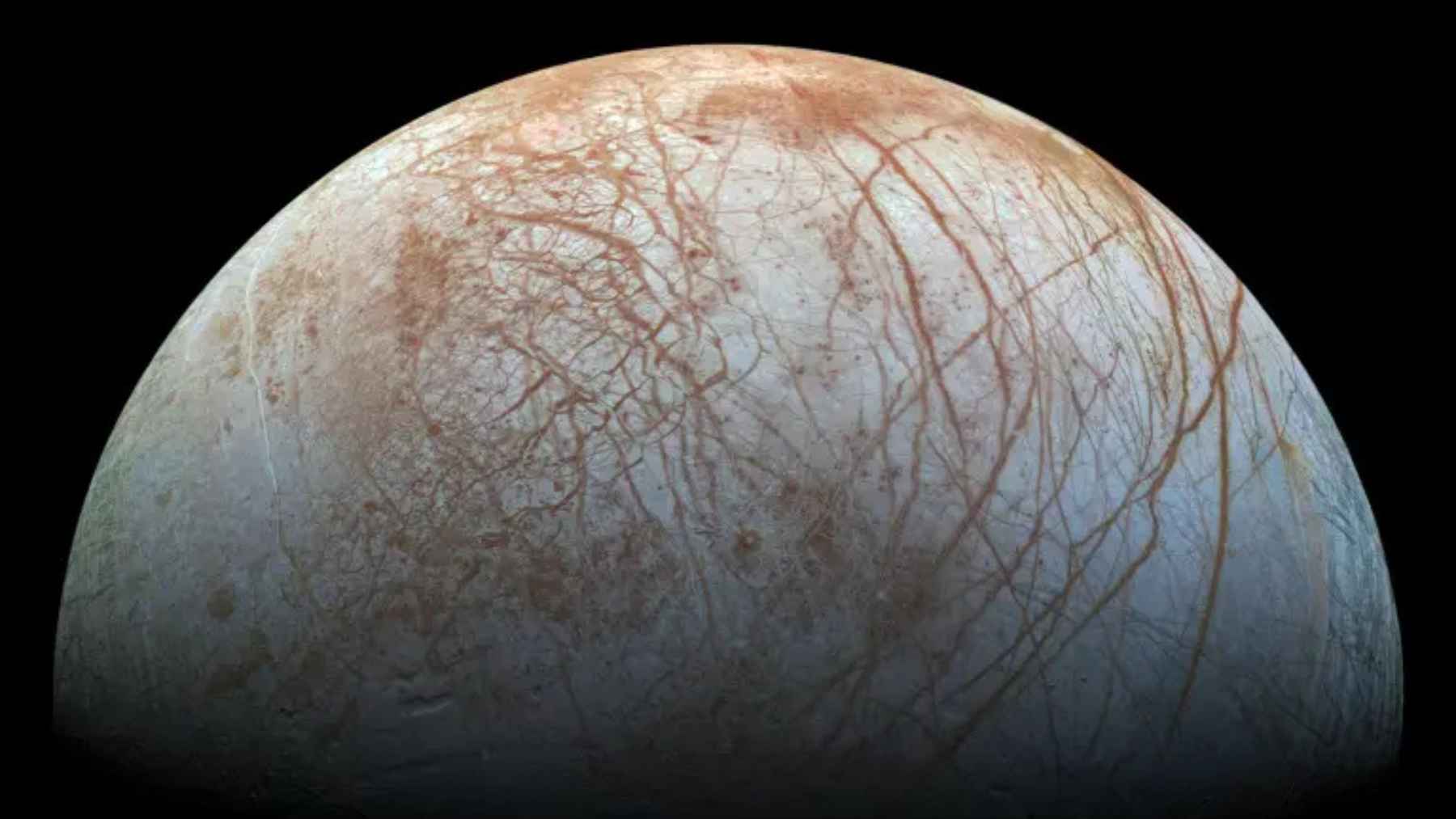

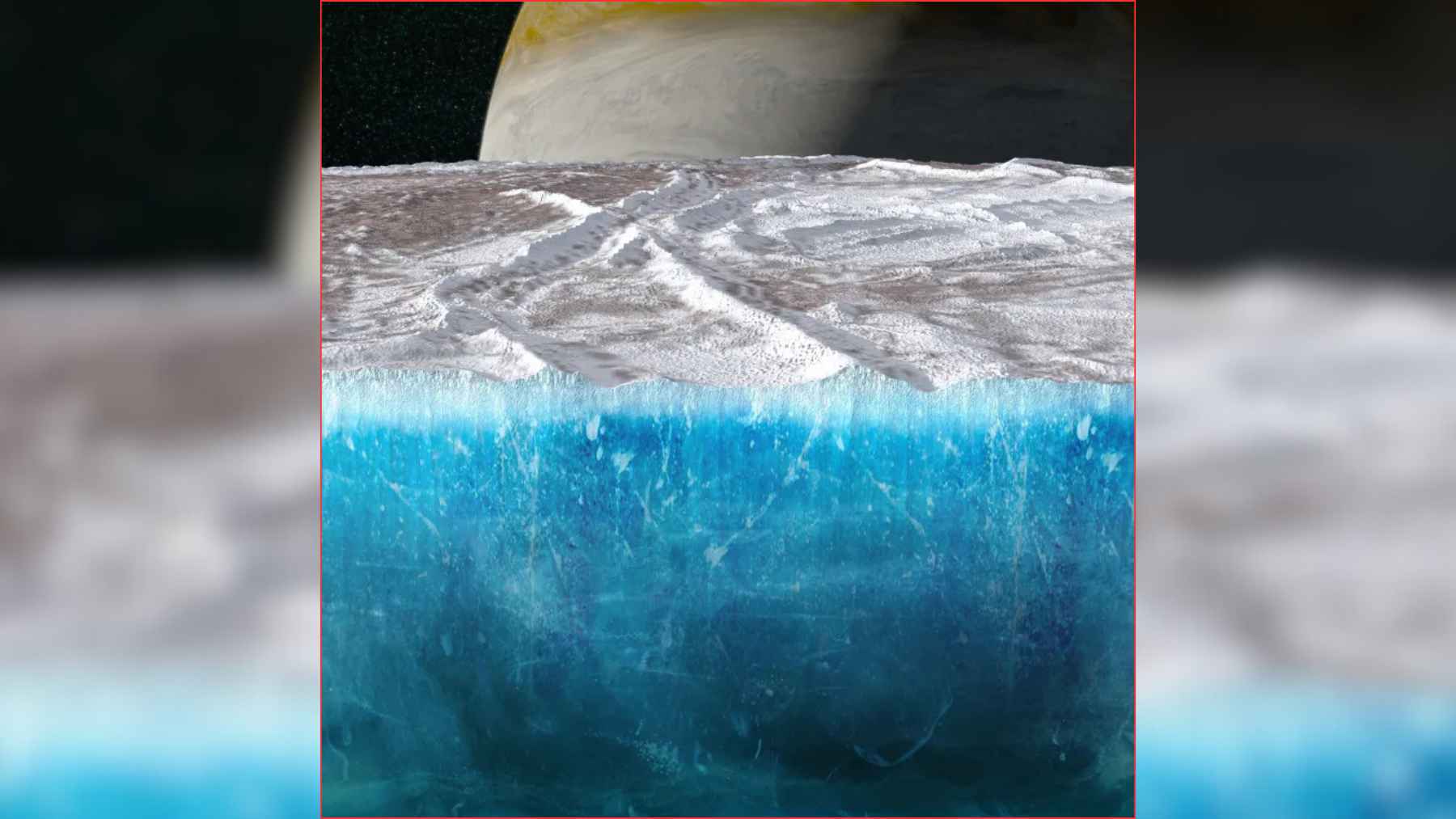

For years, Europa has been the poster child for the idea of hidden oceans that might support alien life. Buried under its bright ice shell, this moon of Jupiter seems to hold more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined, which has made it a favorite target for science fiction and serious research alike.

A new study led by planetary scientist Paul Byrne now suggests that Europa’s deep seafloor may be far quieter than many had hoped. If that picture is right, the ocean beneath the ice could be cold, dark, and almost completely inactive at the bottom, which would make life there much harder to sustain.

Europa’s hidden ocean under new scrutiny

Europa is thought to wear a shell of ice around 10 to 15 miles thick, with a global ocean that may stretch another 60 miles down. Even though the moon is a bit smaller than Earth’s own moon, that huge water layer means Europa likely holds more liquid water than our entire planet.

Scientists have long imagined that this ocean might resemble Earth’s deep seas in some ways. On our planet, hot springs and vents on the seafloor feed rich ecosystems that can survive without sunlight, powered only by chemical energy rising from below.

If Europa had similar vents, it could, in theory, offer a home for microbes clinging to rocky outcrops far beneath the ice.

How the team modeled the seafloor

Byrne and his colleagues did not have a submarine to send into Europa’s ocean, so they turned to physics and geology instead. They combined what is known about the moon’s size, the makeup of its rocky interior, and the strength of Jupiter’s pull, then compared that picture with what we see on Earth and on our own moon.

Read More: Jupiter’s moon could be dead inside

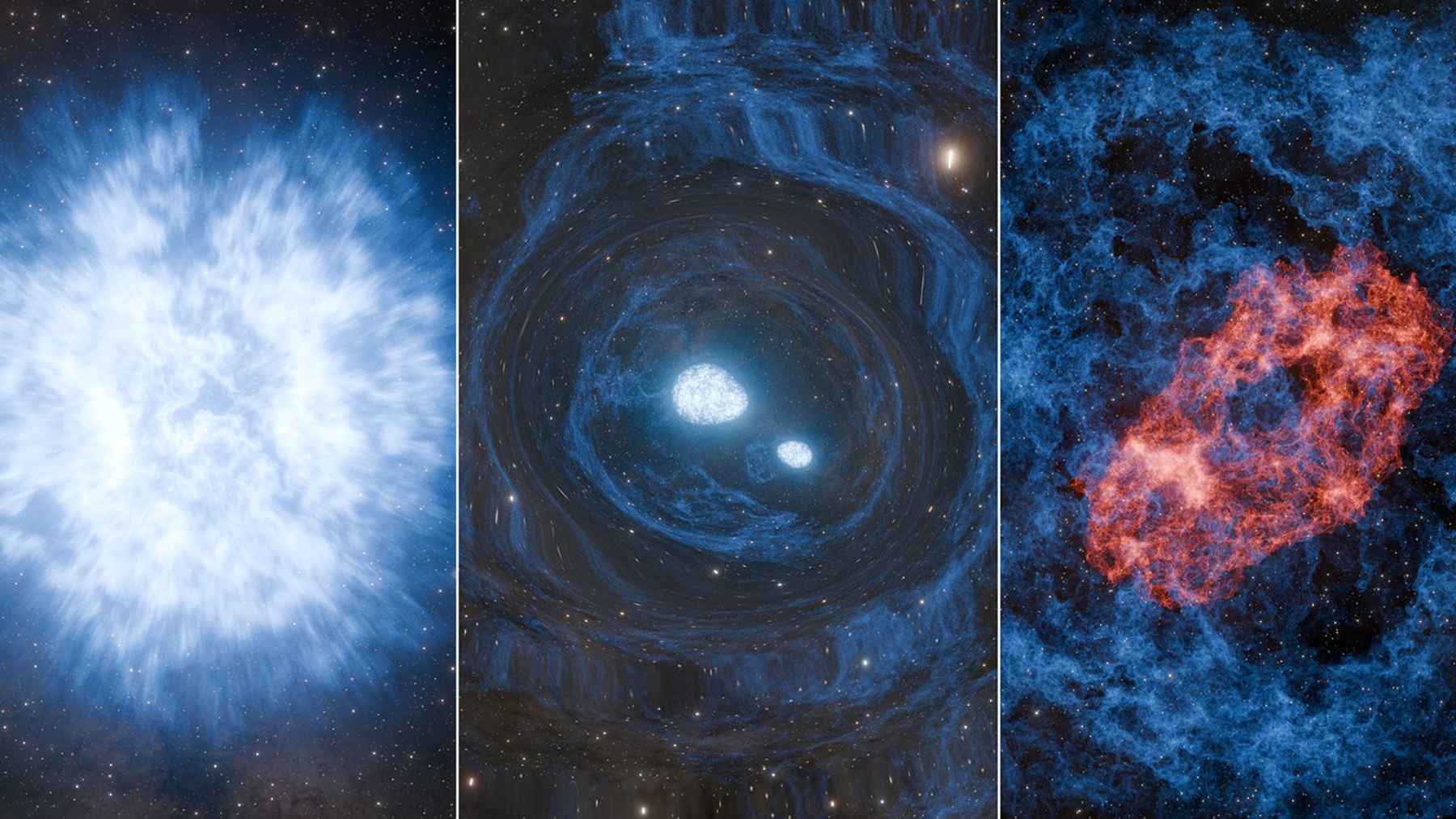

At the heart of their work is a simple idea. Tectonic motion is the slow shifting of rigid plates of rock, like the plates that make up Earth’s crust, driven by heat from inside a planet or moon. The team calculated that any heat from Europa’s rocky core would have leaked away billions of years ago, leaving the interior too cool and rigid for that kind of movement today.

They also examined tidal heating, which happens when gravity flexes a world again and again. On Jupiter’s inner moon Io this process is extreme, fueling constant eruptions that make Io the most volcanically active body in the solar system. Europa orbits farther out on a more even path, so the study concludes that tides there are too weak to keep the seafloor geologically lively.

A quiet seafloor and the chances for life

Putting those pieces together, the researchers argue that Europa’s seafloor likely has little or no active faulting, volcanism, or hot hydrothermal vents. Byrne put it bluntly, saying that if a remote control submarine could cruise along the bottom of the ocean there, it probably would not see fresh fractures, erupting volcanoes, or jets of hot water rising from the rocks.

In his view, such a still environment matters because life, at least as we know it, usually needs a steady source of energy. On Earth, deep ocean communities thrive near vents where hot, mineral-rich water gushes out of the crust, providing fuel for microbes at the very base of the food chain. A cold, stable seafloor with little heating from below would struggle to power similar ecosystems.

For that reason, the study suggests that today’s Europa may not offer the right mix of heat and chemistry for life to gain a foothold at the seafloor. Byrne notes that the energy simply does not seem to be there to support living organisms in the present era, although the moon’s past conditions might have been different.

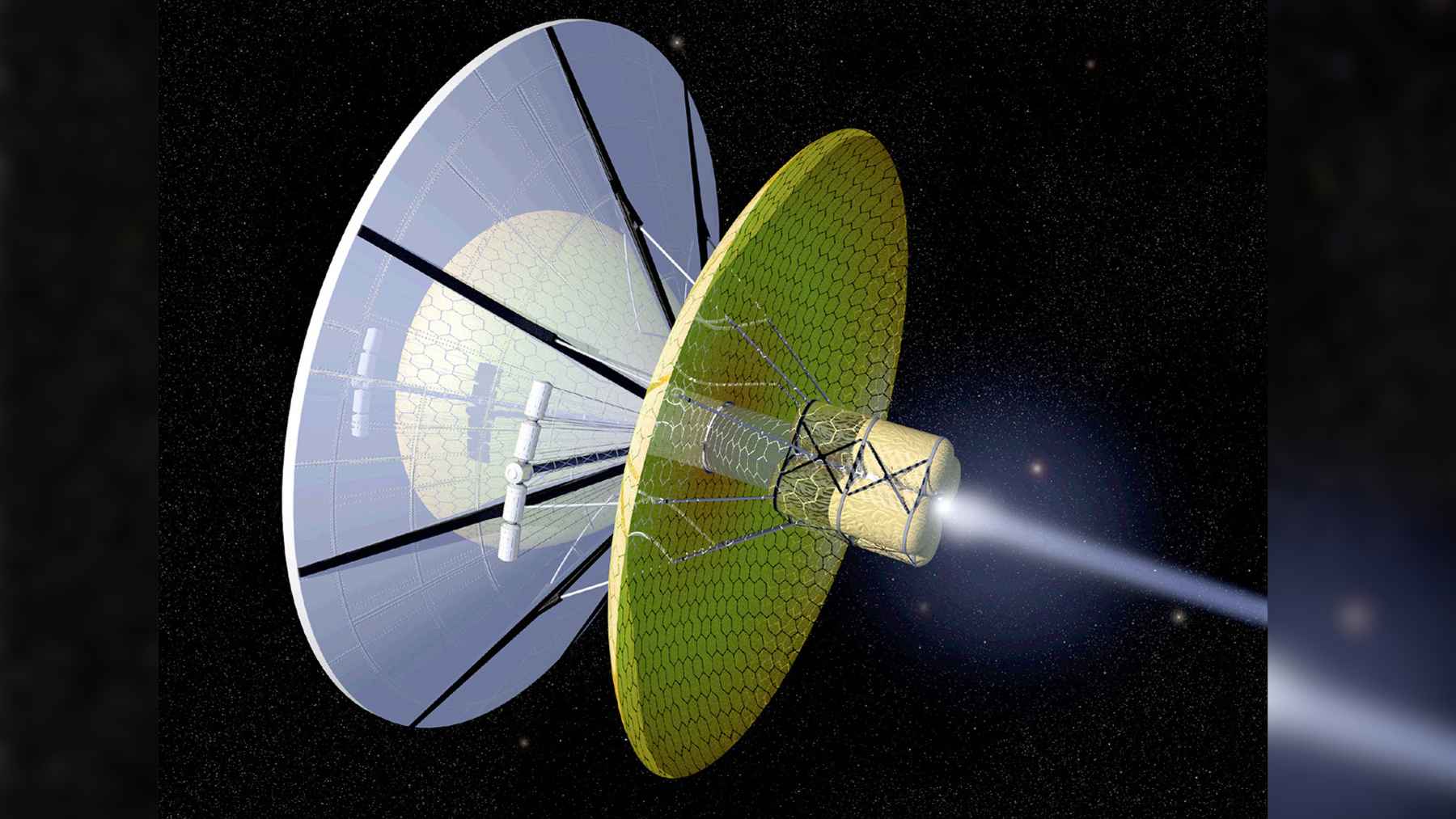

Europa Clipper and the next wave of answers

Despite the sobering results, interest in Europa is not fading. The Europa Clipper spacecraft is scheduled to fly by the moon in the spring of 2031, taking close up images of the surface and measuring the thickness of the ice and the depth of the ocean with far greater precision. That mission, championed in part by planetary scientist Bill McKinnon and colleagues at the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences, is expected to provide a much sharper look at how this world works.

Those measurements will test the new study’s predictions about Europa’s interior and could reveal subtle signs of activity that current models miss. Byrne says he is eager to see what the mission finds, even if the final result is a largely lifeless ocean under the ice. He remains convinced that life exists somewhere in the universe, even if it turns out to be a hundred light years away rather than just beyond Jupiter.

At the end of the day, this work narrows the options for where life might hide in our own solar system while sharpening the tools scientists use to hunt for it.

The main study has been published in Nature Communications.