Imagine trying to fix two very different leaks in the same house. One drip never really stops. The other gushes hard for a short time, then fades away. That mirrors the problem climate scientists face with carbon dioxide and methane.

A new study in the journal Nature Climate Change suggests that temporary removals of CO2 from the air can be tuned to match the short but intense warming from methane. The researchers calculate that storing 87 metric tons of CO2 for about thirty years can offset the climate impact of one metric ton of methane, as long as the timing is aligned with the methane pulse.

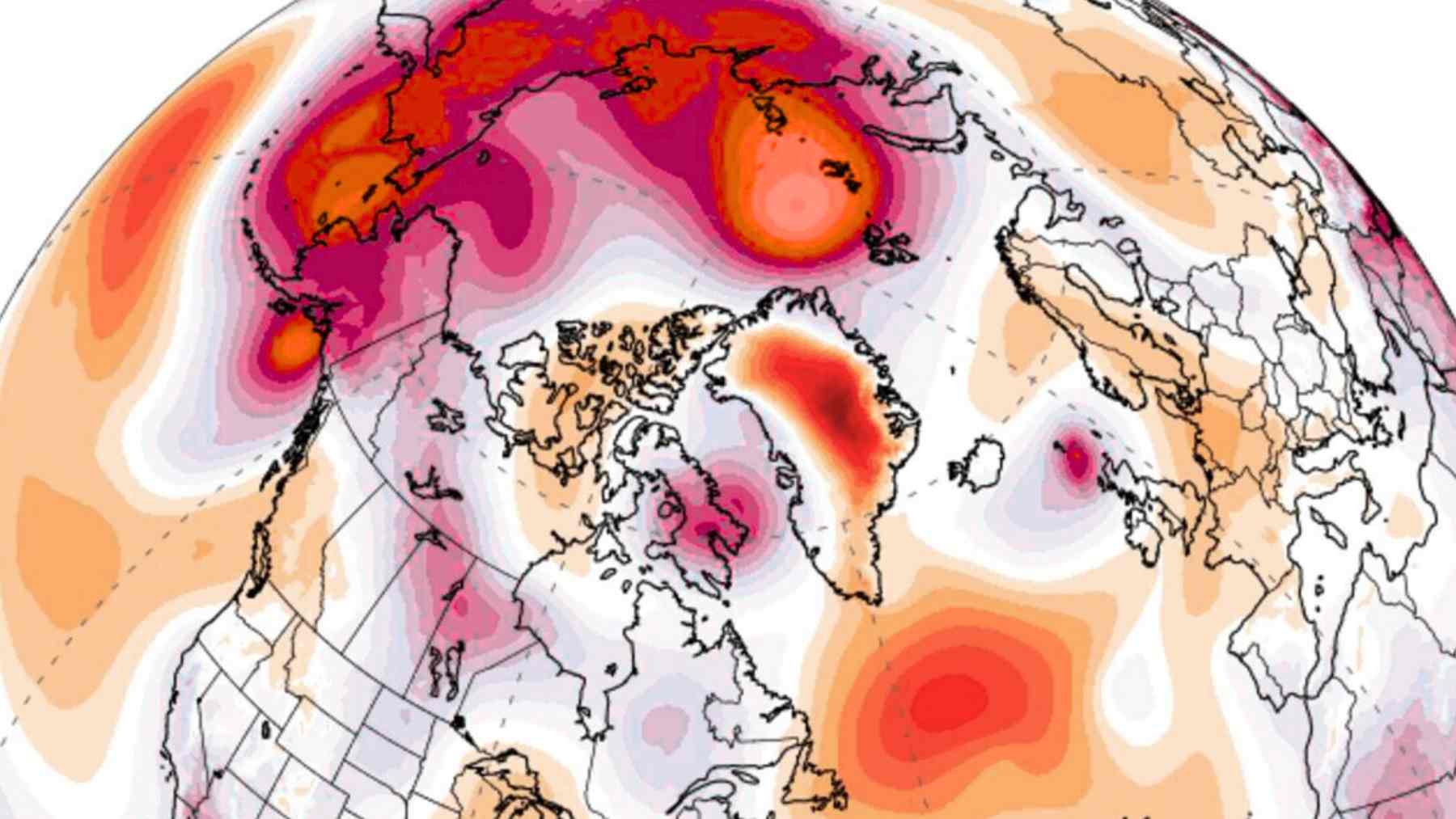

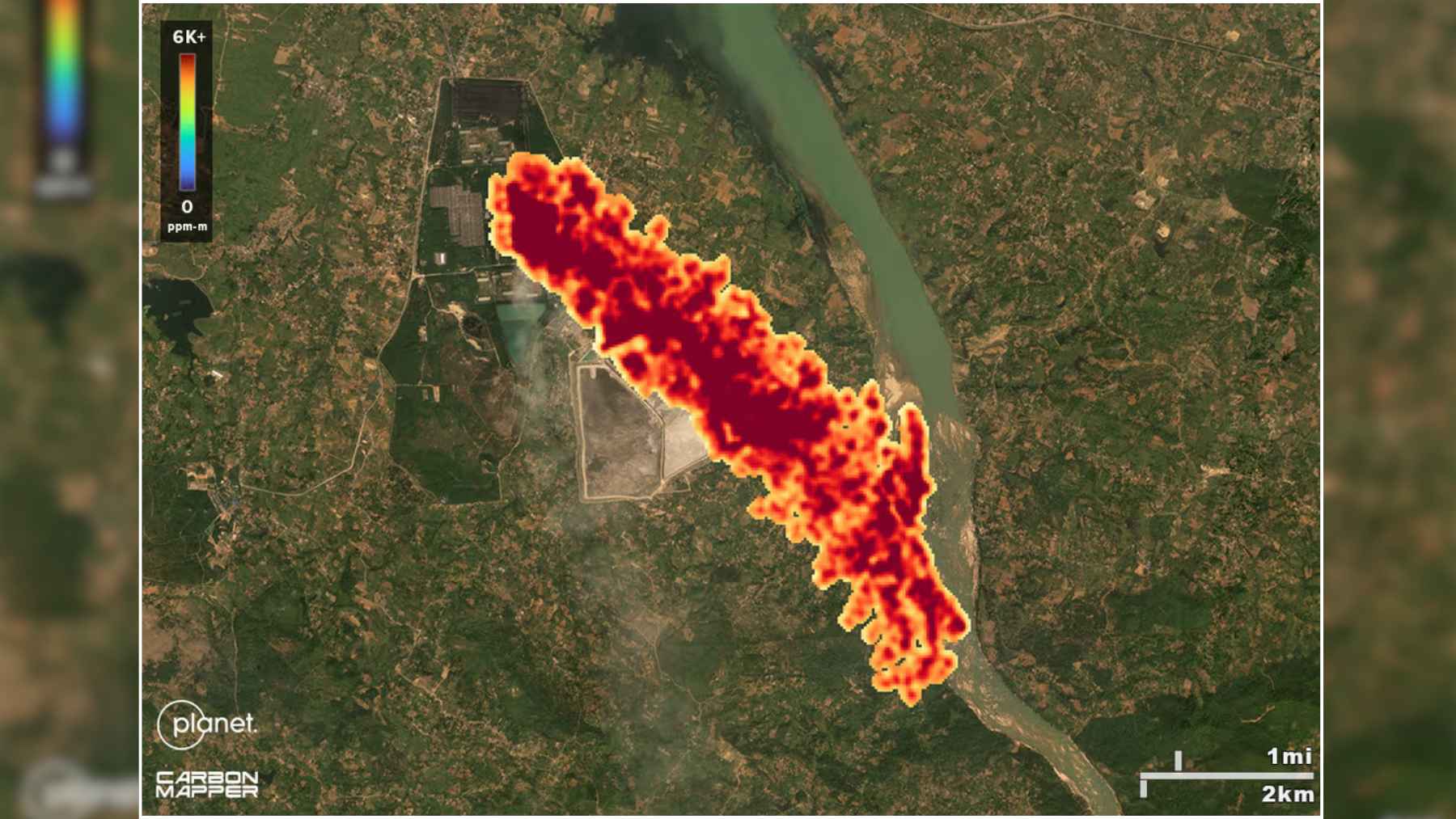

Methane is the second-most-important driver of global warming after CO2 and has added about half a degree Celsius to global temperature since pre-industrial times. It comes from everyday activities that show up on our dinner plates and energy bills, such as cattle, rice paddies, landfills and leaks from fossil gas.

Unlike CO2, which lingers for centuries, methane creates a strong warming spike that lasts on the order of thirty years before easing off. So what do you do about the methane you cannot easily shut off next year?

Matching a short-lived gas with short lived forests

Nature-based carbon projects, such as afforestation, have often been criticized because they do not lock carbon away forever, since trees can burn, be cut down or die from pests. The new research argues that this supposed weakness can actually be a useful feature when dealing with methane, because the gas itself has a temporary effect.

If methane warms the planet strongly for about thirty years, then a removal project that takes CO2 out of the air for the same length of time can mirror that pulse and cool the climate over roughly the same window.

The authors use climate and economic models to show that 87 tons of CO2 removed for thirty years gives about the same reduction in long-term climate damages as avoiding one ton of methane in the first place.

Why thirty-year contracts matter

Permanent CO2 storage in rocks or deep geological formations is expensive and hard to monitor over centuries. Nature-based projects can be cheaper, with many forest-based removals estimated at below $20 per ton of CO2, but investors and regulators worry about what happens after a few decades.

By focusing on thirty-year contracts, the researchers place carbon projects on a timescale people already understand. Instead of asking a forest owner to guarantee storage essentially forever, a thirty-year deal can be monitored, insured and, if needed, renegotiated.

A new lane for nature-based solutions

The authors argue that this approach could reopen climate finance for nature-based removals that carbon markets had sidelined over permanence concerns. As co-author Wilfried Rickels puts it, temporary CO2 removals relieve the climate “precisely when it matters most, when methane causes the greatest damage”.

The authors suggest that temporary removals should be used specifically for residual methane, especially from agriculture and land use, where emissions remain even in very ambitious climate pathways. Permanent CO2 removals, such as geological storage or mineral weathering, would still be needed for fossil CO2 that stays in the atmosphere almost indefinitely.

Not a free pass for methane

Experts are quick to stress that none of this replaces the urgent need to cut methane at the source. Global assessments have repeatedly warned that delaying methane action makes it much harder to keep warming below two degrees Celsius and that large cuts this decade would pay off quickly in reduced heat, drought and crop losses. Temporary removals are meant for the stubborn leftovers, not for business as usual.

For consumers, the idea may sound abstract today. Yet it could quietly shape the next wave of climate labels, carbon credits and even the choices behind the price on our electric bill or the cost of a hamburger.

The study was published on Nature Climate Change.