The Arctic is heating faster than almost anywhere on Earth and now it is heating up politically too. NATO’s top commander in Europe, General Alexus Grynkewich, has warned that the region has become a “front line for strategic competition” as Russian and Chinese warships step up joint patrols in newly-opened waters.

For environmental scientists, that phrase lands with a chill. The same thinning ice that worries climate experts is also drawing warships, oil tankers and surveillance drones into fragile seas that were once locked under snow for most of the year. In other words, global warming is not only reshaping the Arctic climate, it is reshaping security policy.

Grynkewich told a security conference in Sweden that Russia, China, Iran and North Korea are deepening their cooperation, from Ukraine to the High North.

In the Arctic, he said Russian and Chinese vessels are conducting more frequent joint patrols and he argued that Chinese icebreakers and research ships are using their time in the ice to gather military relevant data rather than, as he put it, “studying the seals and the polar bears.”

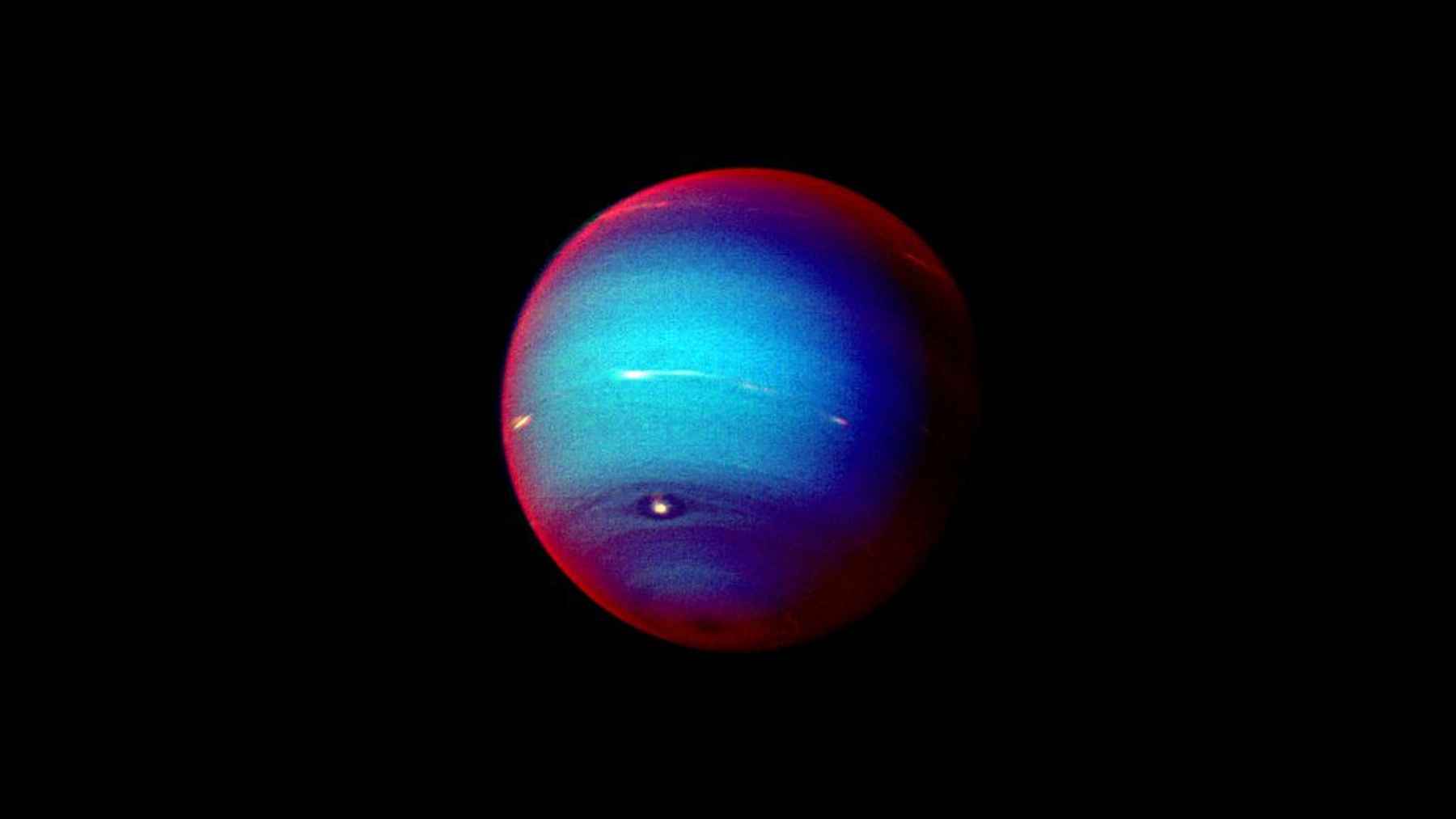

A region warming at record speed

The scientific backdrop is stark. Satellite records and climate models show that large parts of the Arctic Ocean have warmed at least four times faster than the global average since the late nineteen seventies.

Between October 2024 and September 2025, the region recorded its hottest year in more than a century, with sea ice extent hitting record lows and the oldest, thickest ice shrinking by more than 95% compared with the 1980s.

Less ice means more open water. That makes it easier for ships to move along routes such as the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s coast and future central Arctic passages that were once choked with multi-year ice. Researchers already see rapid growth in vessel traffic and in emissions from shipping, including a nearly 80% jump in black-carbon pollution from Arctic ships between 2016 and 2022.

Warships, whales and underwater noise

More ships do not only mean more flags on an electronic map. They also mean more noise in waters that used to be remarkably quiet. Cold Arctic seas transmit sound very efficiently, so even modest increases in traffic can boost background noise levels over huge distances and interfere with the way bowhead whales, narwhals and walrus communicate and navigate.

Conservation groups and Arctic Council experts warn that this growing soundscape is already stressing marine mammals that rely on echolocation and long-distance calls. Slower steaming, rerouting around key feeding grounds and cleaner propeller technology can cut noise significantly, yet those measures are voluntary in many areas.

On top of that, the soot-like black carbon from ship exhaust settles on snow and ice, darkening the surface so it absorbs more sunlight. Studies suggest this pollution is a key driver of Arctic sea ice loss and recent work indicates that emissions from European linked Arctic shipping were higher than earlier estimates.

Baltic Sentry, Eastern Sentry and the battle on the seabed

NATO’s response sits mostly in the background of these environmental shifts but it is closely tied to them. Melting ice and rising tensions have already produced real world shocks in nearby seas, such as the 2022 explosions that crippled the Nord Stream pipelines in the Baltic.

That event released hundreds of thousands of tonnes of methane, one of the largest single methane leaks ever measured.

Worried about further attacks on pipelines and internet cables, NATO launched a new activity called Baltic Sentry in January 2025. The effort brings together frigates, patrol aircraft, naval drones and national surveillance systems to watch over energy lines and data cables on the seabed and to respond more quickly if something goes wrong.

In September 2025, after a spike in Russian drone and aircraft incursions near Allied airspace, the Alliance added Eastern Sentry, a flexible activity that reinforces air, sea and land defenses along the entire eastern flank while building directly on the experience of Baltic Sentry.

For everyday life, these operations are about more than military posture. They help protect the cables that carry your video calls and bank transfers and the power lines that keep the lights on during dark northern winters.

Oil tankers, shadow fleets and environmental risk

Layered onto this is a growing fleet of shadow or dark tankers that ferry sanctioned oil through the Baltic and Arctic using older, poorly-maintained ships that often lack proper insurance. Analysts estimate this fleet now numbers in the hundreds or even more than a thousand vessels worldwide and warn that many were almost scrap ready before being brought back into service. Governments and militaries see them as a sanctions problem. Environmental experts see a high risk of spills in cold, hard to clean waters.

A major accident in narrow straits or near coastal nature reserves would not stay a local story for long. Oil trapped under sea ice, or methane streaming from a ruptured pipeline, would add to the climate burden that is already pushing Arctic ecosystems toward rapid and sometimes irreversible change.

For now, Grynkewich insists he does not see an immediate threat of a direct attack on NATO territory. Yet his description of the Arctic as a front line suggests that decisions about ship routes, pipeline safety and undersea surveillance will increasingly be shaped by a mix of climate physics and hard security thinking.

The choices made there will ripple far beyond polar bears and patrol boats, reaching all the way to the electric bill on your kitchen table.

The official statement was published by NATO.