A walk in the woods can feel quiet, even ordinary. But in Pennsylvania, one boy noticed tiny “seeds” piled near an ant nest, and that small detail helped kick off a new scientific finding about how ants move things through forests.

A new study shows that some oak galls can get carried by ants in much the same way ants carry certain seeds. The twist is that the payoff may not be about traveling farther, but about ending up somewhere safer.

A backyard clue that turned into a real research question

At first glance, the “seeds” near the nest looked like the usual forest clutter. You’ve probably seen ants do this on a sidewalk too, hauling crumbs that seem way too big for them. So why were these little objects showing up in a neat spot near an ant entrance?

That question guided fieldwork in western New York and central Pennsylvania, where researchers watched what ants actually did with the galls. They also built controlled tests to see whether ants were making a choice or just grabbing whatever was nearby.

A key part of the project came together under the lead of Robert J. Warren II at SUNY Buffalo State University, who studies how ants move seeds and shape relationships between species. The study’s central claim is simple to picture, some galls are effectively “packaged” to get picked up.

What an oak gall is, in plain language

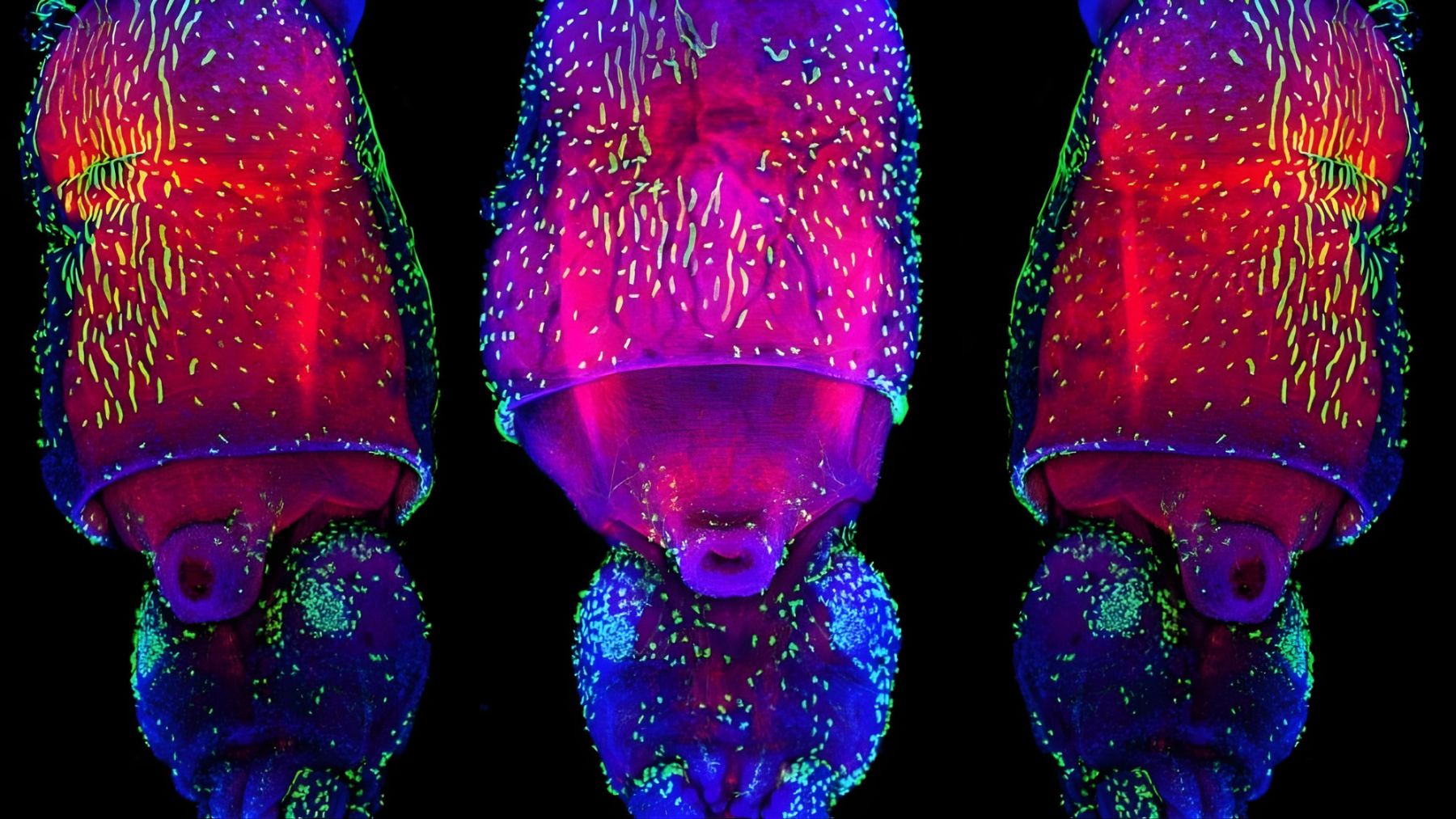

Oak galls are small growths that show up on or under oak trees, often like BB sized spheres you might notice in late summer. They are not seeds, even though they can look like them on the ground.

They form when cynipid wasps lay eggs and trigger the tree to build a swollen chamber of plant tissue. The wasp larva develops inside that chamber, using it as both food and shelter until it is ready to emerge.

This matters because forests already have a well-known system where ants move seeds, a process called myrmecochory. In that setup, seeds come with a fatty “snack” attached, and ants carry the seed home, eat the snack, and often leave the seed intact.

The “cap” that makes ants treat a gall like a seed

Some galls grow a pale, fatty cap called a kapéllos, and ants seem drawn to it. In choice tests, ants largely ignored similar sized galls without the cap, but handled capped galls the way they handle seeds that carry a food reward.

Chemical work backed that up by showing the cap contains fatty molecules that overlap with the fats found in seed food bodies. Think of it as the same basic signal ants already recognize, like a familiar smell that tells them “this is worth carrying.”

Researchers also ran field “cafeteria” setups and lab assays, and they recorded nest traffic both at night and during the day. Their data and code were preserved in a public repository, which makes it easier for other teams to double-check the work through the archived dataset.

Why the ant nest looks like the real prize

If the goal were simply distance, you might expect the story to end once a gall gets moved away from the tree. But cameras added another layer, animals like birds and rodents ate many galls left exposed on the forest floor, while capped galls were more likely to reach ant nests intact.

Inside nests, the pattern was telling. Ants removed the cap but left the rest of the gall unbroken, which could mean the larva ends up sheltered in a dry, defended space where predators and parasites have a harder time getting in.

That’s one reason researchers frame this as convergent evolution, unrelated organisms arriving at a similar solution to the same problem. A global analysis helps explain why these fatty signals show up again and again across many flowering plants, and a broader review notes that a relatively small set of ant species do much of the seed moving in forests.

As Andrew Deans at Penn State University put it in a university research story, “This multi-layered interaction is mind-blowing. It’s almost hard to wrap your mind around it.” And it raises a big open question, did gall “lures” come first, or did seeds teach ants what to look for?

The study was published on The American Naturalist.