They do not follow river channels, they show no signs of mining, and they look nothing like normal caves. Many of the passages are longer than 600 yards and tall enough for an adult to walk through without bending. The leading idea is that giant extinct ground sloths dug these colossal shelters, turning parts of South America into a maze of underground homes.

Unearthing the ancient tunnels

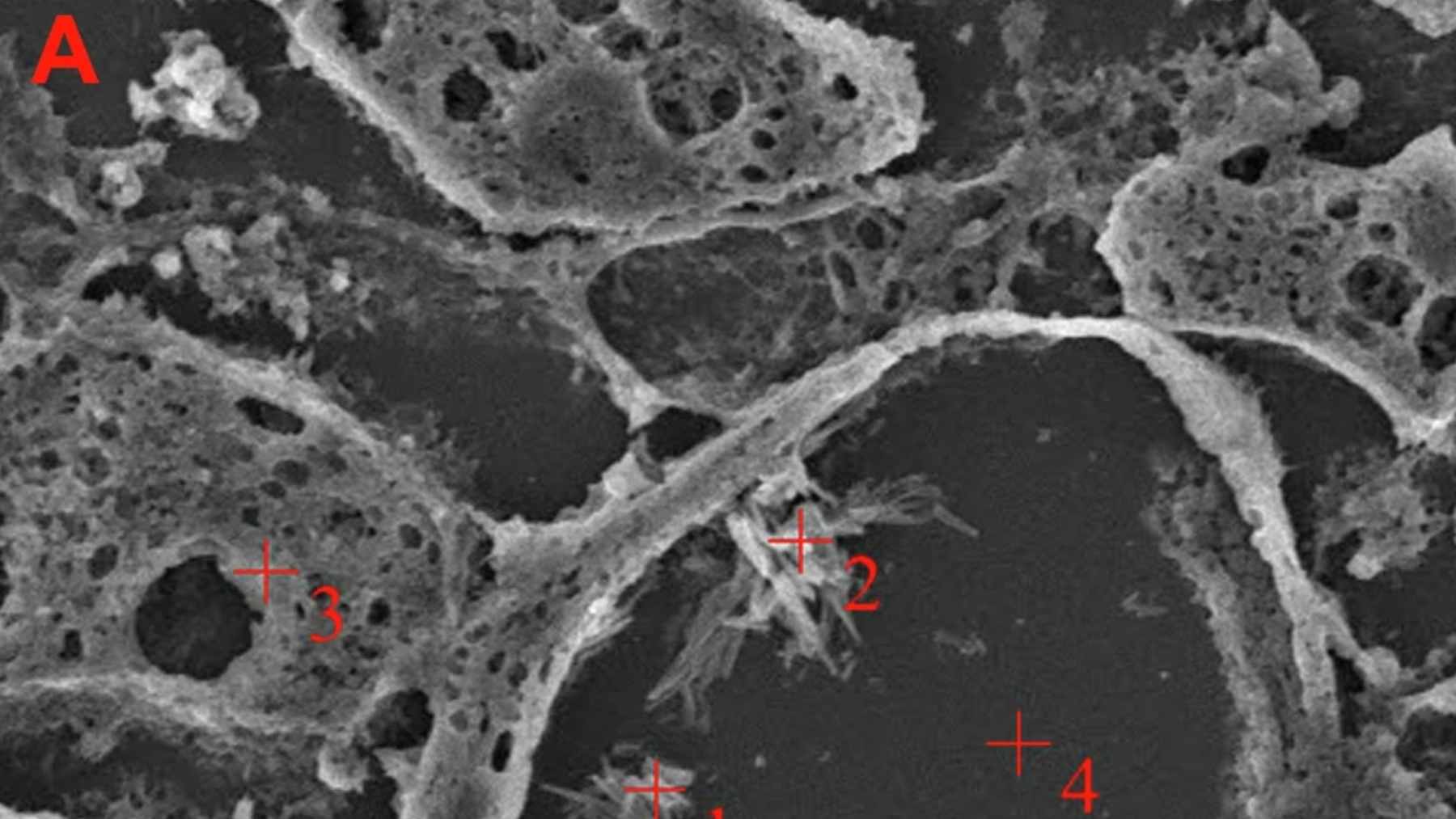

Over the past decade, a detailed study mapped more than 1,500 giant burrows across southern and southeastern Brazil. These tunnels can reach several hundred feet in length, branch into side passages, and display long parallel claw marks etched into their walls.

The work was led by Heinrich Frank, a geologist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil (UFRGS). His research centers on paleoburrows, fossil tunnels carved by extinct large animals that once reshaped the landscapes of southern South America.

Many passages appear in consolidated sands, sandstone, or weathered volcanic rock, materials that are hard for machines and harder for humans with simple tools. Collapsed ceilings and overlapping tunnels show that some routes were widened and reused, a pattern outlined in a chapter on Cenozoic tunnels. Geological processes such as landslides, joints, and natural caves rarely create long, nearly circular tunnels that slope up and down or branch like these.

Frank notes that tunnel walls are packed with claw marks, sometimes in three parallel grooves, right where a digging limb would bite into rock. Similar tunnels crop out along road cuts in Argentina, where they intersect and crisscross in dense clusters on some hillsides.

Taken together, the layout looks less like an accident of erosion and more like a network of shelters dug and maintained over long periods.

Clues pointing to giant ground sloths

To identify the tunnel makers, scientists match burrow size and claw patterns with fossil skeletons from the same regions.

The biggest tunnels are at least 6 feet across and roughly as tall, which narrows the candidates to giant ground sloths and armadillos.

The claw traces are broad and shallow, matching the long curved claws of sloths more closely than the shorter claws of armored diggers.

These burrows are a textbook example of megafauna, very large animals from the recent geological past, reshaping the ground as they moved and rested.

One top candidate is Megatherium, the best known South American giant ground sloth from the late Ice Age.

Fossils suggest Megatherium weighed up to four tons and stood 12 feet tall, similar to an elephant, as noted in a museum piece.

It had a long tail for balance and massive forelimbs tipped with curved claws. A sloth built like this could rear up, brace, and dig steadily into sediment or softer rock over many generations.

Humans and sloths on the same landscape

These tunnels date to the Pleistocene, an ice age period that ended about 11,700 years ago, when humans and giant sloths shared the Americas.

In New Mexico’s White Sands, a footprint paper describes trackways where barefoot humans stepped into sloth prints and then followed them for distances.

The sloth trackways twist sharply and form circles where the animals rear and swing their forelimbs while human footprints cluster nearby.

“Human interactions with sloths are probably better interpreted in the context of stalking and/or hunting,” wrote David Bustos, a park scientist.

The trackways show that sloths sometimes turned to face their pursuers, leaving circular patterns where they reared and lashed out with their claws.

“Their strong arms and sharp claws gave them a lethal reach and clear advantage in close-quarter encounters,” wrote Matthew Bennett, a geologist.

Humans in North America were bold enough to stalk such dangerous animals across open lakebeds, so people farther south likely also hunted them.

In that context, long underground refuges would have helped sloths avoid hunters, big cats, and sudden swings in temperature on exposed slopes.

Why paleoburrows matter today

Each paleoburrow preserves details that bones alone cannot, from the curve of the tunnel to the texture of its scratch covered walls and floors.

They are a kind of trace fossil, preserved evidence of ancient activity such as burrows, footprints, or feeding marks rather than the bodies themselves.

Taken with surface fossils, these underground records help scientists map where different sloth species lived and how they divided up habitats across the Americas.

A review of Pleistocene sloths shows that they lived from grasslands to forest edges, and paleoburrows add behavioral context to their fossil ranges.

The tunnels also feed into efforts to understand how the loss of large animals changed soils and vegetation after the Ice Age.

Studies of extinct megafauna in many regions find that their disappearance reshaped ecosystems and nutrient flows, as shown in one analysis of large herbivores.

As more paleoburrows are surveyed and mapped, they will link what we know from fossils and footprints into a picture of Ice Age life.

The giant tunnels under Brazil and Argentina become more than curiosities; they stand as traces of how ancient sloths, people, and landscapes shaped one another.

The study is published in Science Advances.