Octopuses can solve puzzles, learn quickly, and sometimes act like they are just messing with us. Now, researchers say the roots of that intelligence may be hiding in something tiny and surprisingly familiar: the way a cephalopod embryo builds its nervous system.

A team tracked nerve cells forming inside squid embryos and found a development pattern that closely resembles what happens in vertebrates, including humans. The idea is simple but powerful. Different animals may arrive at big, complex brains by using some of the same basic building steps.

Octopus intelligence shows up in everyday-looking tests

Scientists have long collected clues that octopuses are more than instinct machines. In one lab setup, octopuses learned to solve a multi-step food puzzle and then adjusted when the task rules changed, a sign of flexibility rather than rote habit.

They also appear able to learn by watching. A classic experiment reported that Octopus vulgaris could observe another octopus make a choice and then copy that choice later, which is the kind of shortcut learning people associate with “smart” animals.

And then there is self-control, the trait behind resisting a quick snack for a better one. In a “wait-for-the-better-treat” setup, Alexandra K. Schnell and colleagues found cuttlefish, close relatives of octopuses, could hold off on a lesser food reward for up to about two minutes to get what they preferred.

The embryo work that points to a shared “blueprint”

So how do animals with such different bodies end up with brains capable of learning and planning? The new work followed nerve cell creation in embryos using live imaging, basically a way to watch cells develop over time instead of guessing from snapshots.

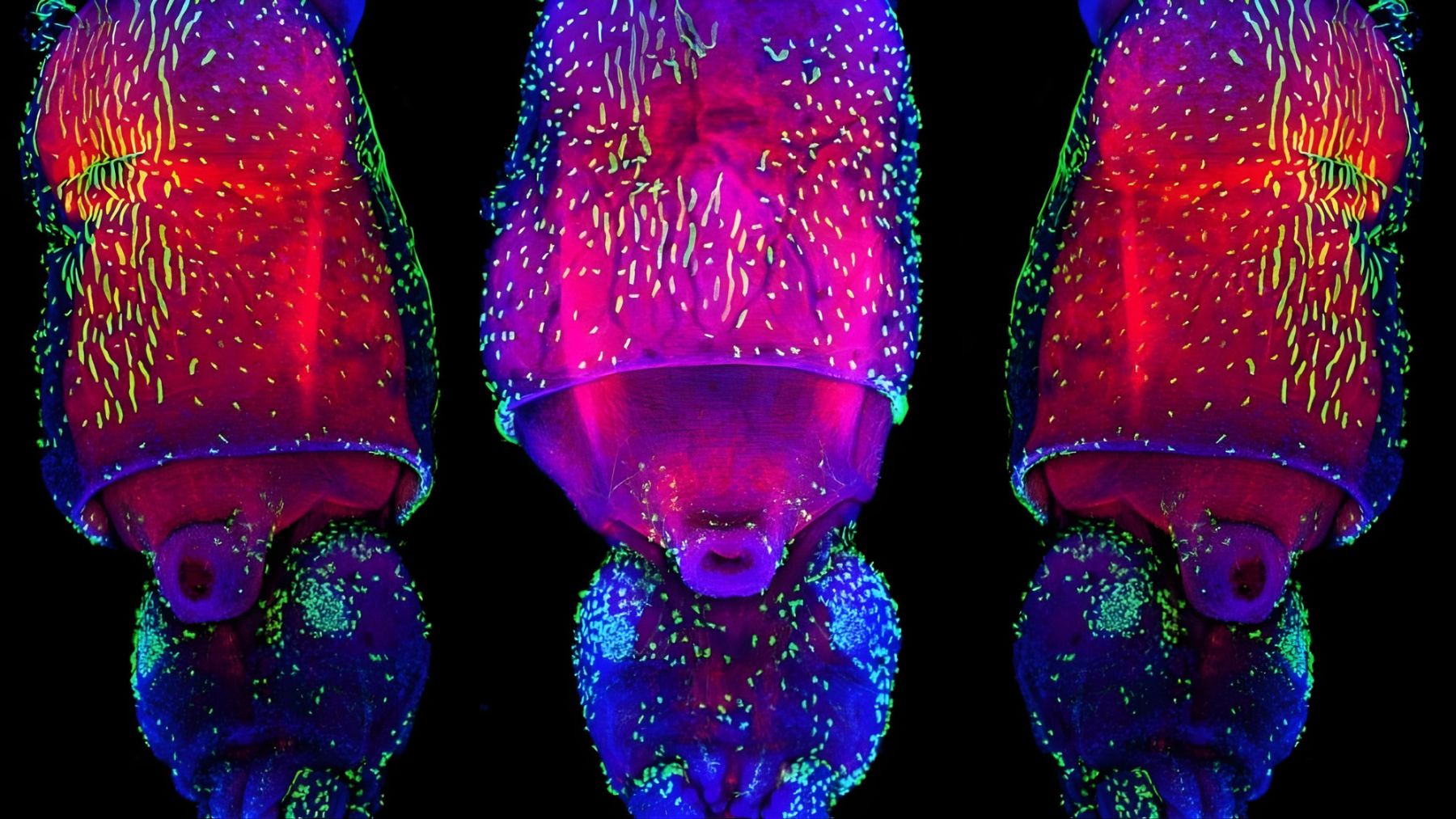

The team focused on the retina, the light-sensing tissue at the back of the eye, in longfin inshore squid embryos. That matters because in cephalopods, a lot of information processing is tied to vision, and the retina offers a clear window into how nervous tissue gets built.

The researchers, led by Francesca R. Napoli and Christina M. Daly, reported that the stem cells making new neurons behaved in ways that looked strikingly like vertebrate development. Kristen Koenig, the senior author, said the similarity was surprising given the evolutionary distance between these groups.

The key concept behind the “recipe” for big brains

Here is the core idea in plain terms. The embryo uses a tightly packed layer of stem cells that divide in an organized rhythm, keeping the growing tissue neat while it produces lots of neurons over time. Think of it like a well-run kitchen line, where the order of steps keeps the output high without turning into chaos.

This is important because it suggests big brains may not require a completely unique trick. Instead, evolution might repeatedly lean on a reliable construction method when a species needs more nerve cells, more wiring, and more computing power to handle a complicated world.

In practical terms, that could help explain why cephalopods can pull off behaviors that feel almost familiar, like exploration, problem-solving, and what keepers sometimes describe as boredom-driven mischief. It also gives scientists a clearer target for future work on how different neuron types appear and connect as the brain grows.

The main study has been published in Current Biology.