Tiny fragments of plastic are no longer just in the ocean, the soil, or the air around us. They are turning up in the most protected organ in the human body. A new study in decedent brain tissue reports that microplastics and nanoplastics are present in the human brain at levels far higher than in the liver or kidney, raising urgent questions about how modern plastic pollution is reaching our nervous system and what that might mean for long-term health.

Autopsy study shows higher plastic levels in the brain than liver or kidney

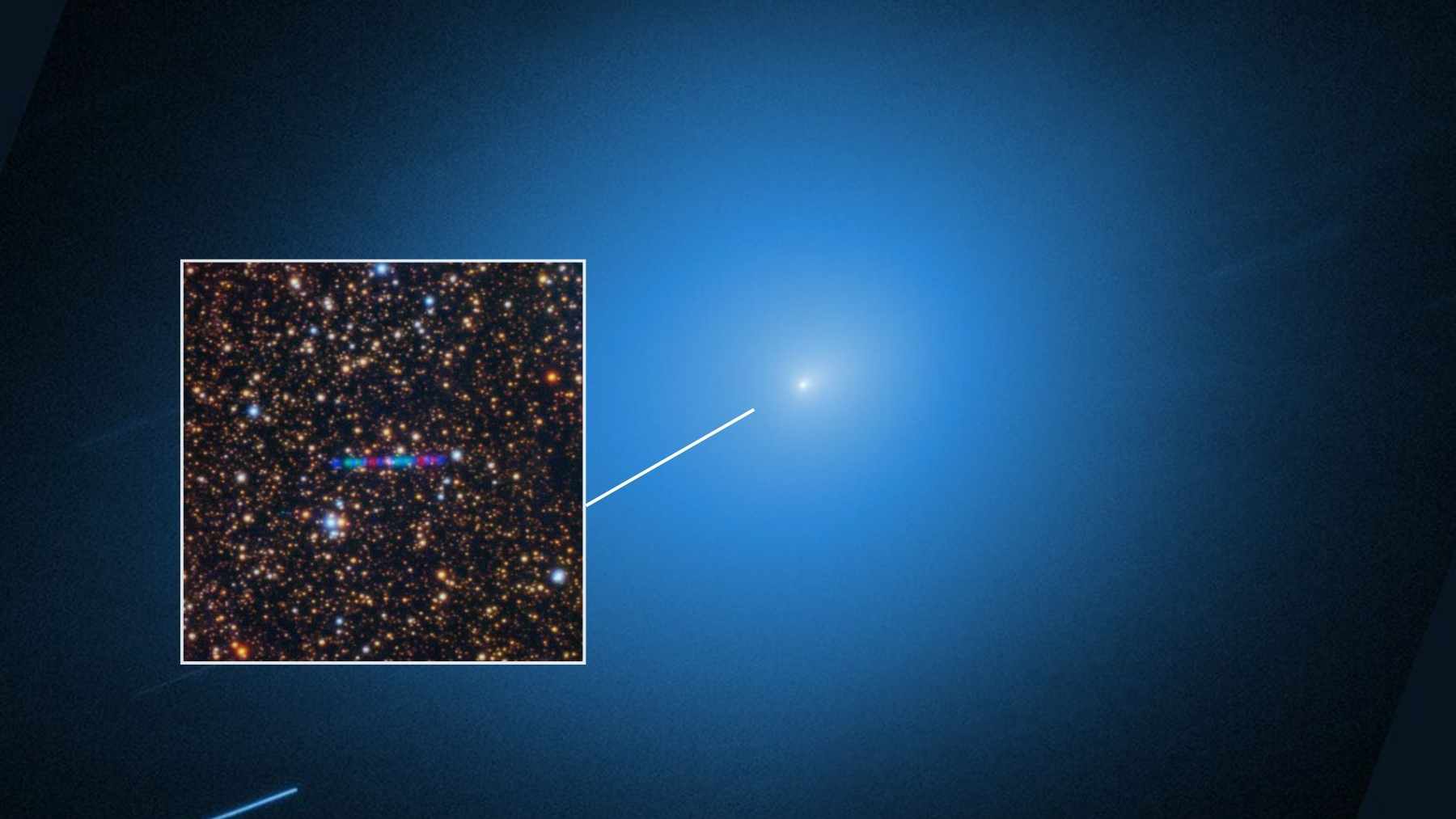

The research team examined autopsy samples from 52 people and compared three organs that often handle toxins and waste. They used a high-precision technique called pyrolysis gas chromatography mass spectrometry together with several imaging methods to detect and identify plastic particles.

The brain samples, all taken from the frontal cortex, contained roughly seven to thirty times more microplastics and nanoplastics than the liver or kidney from the same individuals. On average, the amount of plastic in a single brain sample was comparable to the mass of a small plastic spoon, according to lead author Matthew Campen.

Polyethylene nanoplastic shards and how they show up in brain tissue

Most of those particles were not beads or fibers that you could see with a standard microscope. They were nanoscale shards and flakes, often between one hundred and two hundred nanometers long, and made largely of polyethylene, the same polymer used in plastic bags, food wrap, and many drink bottles.

In brain tissue, polyethylene made up about three quarters of all detected plastics, a higher share than in the liver or kidney. Under electron microscopes, the fragments appeared as jagged chips lodged within the tissue, with especially dense deposits along blood vessel walls and near immune cells in brains from people who had dementia.

Dementia and the blood-brain barrier question

That naturally leads to a worrying question. If there is more plastic in dementia brains, could it be part of what drives disease. For now, the honest answer is that no one knows. In this study, people with documented dementia did show far higher plastic concentrations in the frontal cortex than people of similar age without dementia. Yet dementia also damages the blood-brain barrier and slows clearance of waste.

The authors and independent experts caution that the extra plastic could easily be a consequence of those changes rather than a cause. In the words of one outside neuroscientist commenting on the work, “we cannot say from this study that micro and nanoplastics are causing dementia.”

Why levels may be rising with environmental exposure

Another important observation concerns time. The researchers compared samples collected in 2016 with those from 2024. Brains and livers from 2024 contained markedly more plastic than those from 2016, even though the analytical methods accounted for storage differences.

In contrast, there was no clear pattern with the age, sex, race, or cause of death of the decedents. That suggests people are not simply stockpiling plastic in their organs throughout life. Instead, internal levels appear to track the intensity of recent environmental exposure, which has climbed as global plastic production and fragmentation continue to rise.

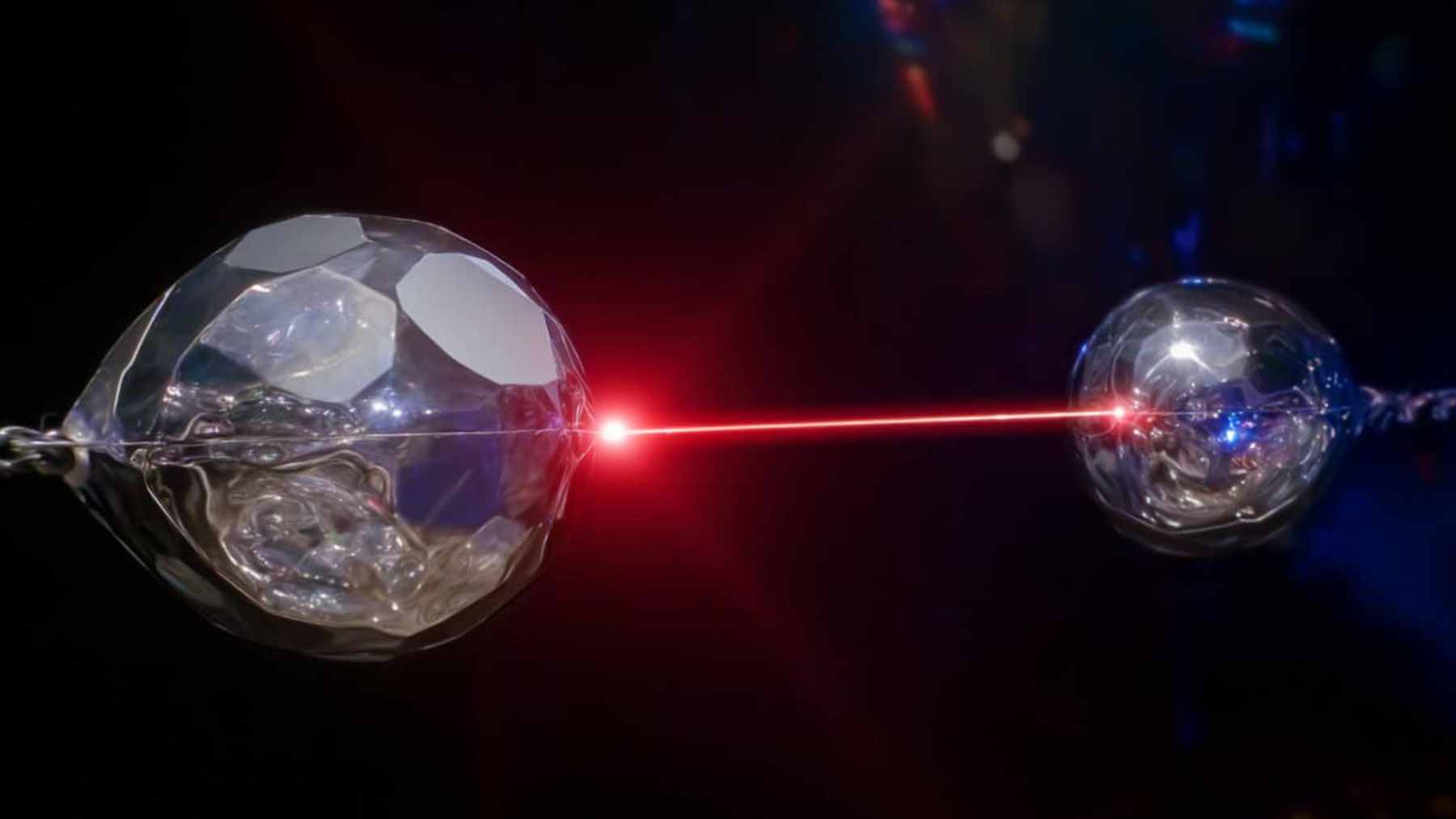

How nanoplastics could cross into the brain

How do these tiny fragments get into such a well protected organ in the first place? The brain is shielded by the blood-brain barrier, a specialized filter that blocks many pathogens and chemicals. Campen and colleagues suspect that the answer lies in the way plastics interact with fats. He compares it to scrubbing a greasy plastic food container at home.

Anyone who has ever fought with a film of bacon fat on a plastic lid knows how stubborn that mix can be. The study authors propose that nanoplastics may hitch a ride with dietary lipids that can cross into brain tissue, although the exact transport routes remain uncertain and will need dedicated experiments to clarify.

What science knows about health effects so far

If all this sounds unsettling, it helps to remember that the toxic picture is still incomplete. Microplastics and nanoplastics have already been detected in human blood, placenta, arteries, testes, and even heart tissue.

Some observational work links their presence to inflammation, cardiovascular events, or reduced sperm count, while animal studies show that very high experimental doses can disturb organ function.

At the same time, clinicians emphasize that the real world doses inside human bodies and the long-term effects on health are only beginning to be mapped. By the researchers’ own admission, measurement tools are still evolving and estimates carry uncertainty.

Practical ways to reduce microplastic exposure

Where does this leave everyday choices, from refilling a plastic water bottle to reheating leftovers in a plastic container. No single habit will flip a switch in the brain. Yet small steps can nudge exposure in the right direction.

Washing hands before meals, removing plastic packaging before microwaving food, choosing reusable glass or stainless steel where practical, and cutting down on single use plastics at home all reduce the number of particles that can travel from packaging into food, air, and eventually our bodies.

On a larger scale, policies that curb plastic production, improve waste collection, and tackle pollution at the source are likely to pay off twice, by protecting ecosystems and, to a large extent, our own organs.

Why this research changes the plastic pollution conversation

At the end of the day, this study turns microplastic pollution from a distant ocean story into something literally inside our heads. It does not prove that plastics in the brain cause disease, but it does show that rising environmental contamination is mirrored by rising internal loads, even in the most guarded tissues.

That finding alone is a strong signal that understanding how these particles move, how they leave, and what they do along the way should be a priority for environmental and health research in the years ahead.

The study was published in Nature Medicine.