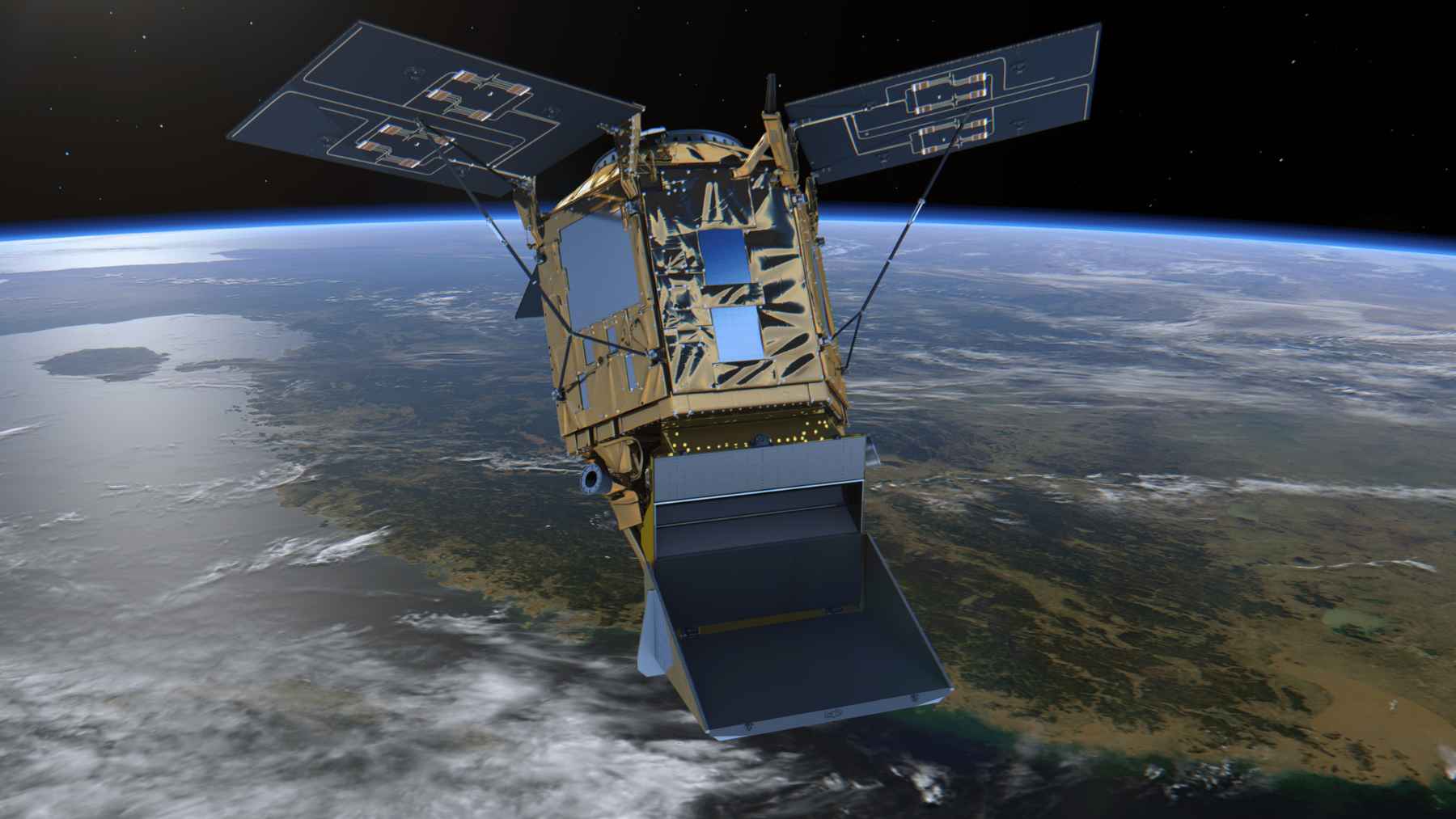

For more than a decade, satellites have watched a brown streak grow across the Atlantic Ocean. In May 2025, that streak reached a new record of about 37.5 million tons of floating seaweed stretching over 5,400 miles, roughly twice the width of the continental United States. Scientists call it the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, and it is now big enough to be tracked from space almost every year.

A new scientific review led by marine scientist Brian Lapointe at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute pulls together forty years of data to explain how this happened. Published in the journal Harmful Algae, the work shows that a mix of natural forces and human made nutrient pollution has turned a once patchy seaweed into a recurring ocean-scale belt that threatens coasts, economies, and even the climate.

What is the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt?

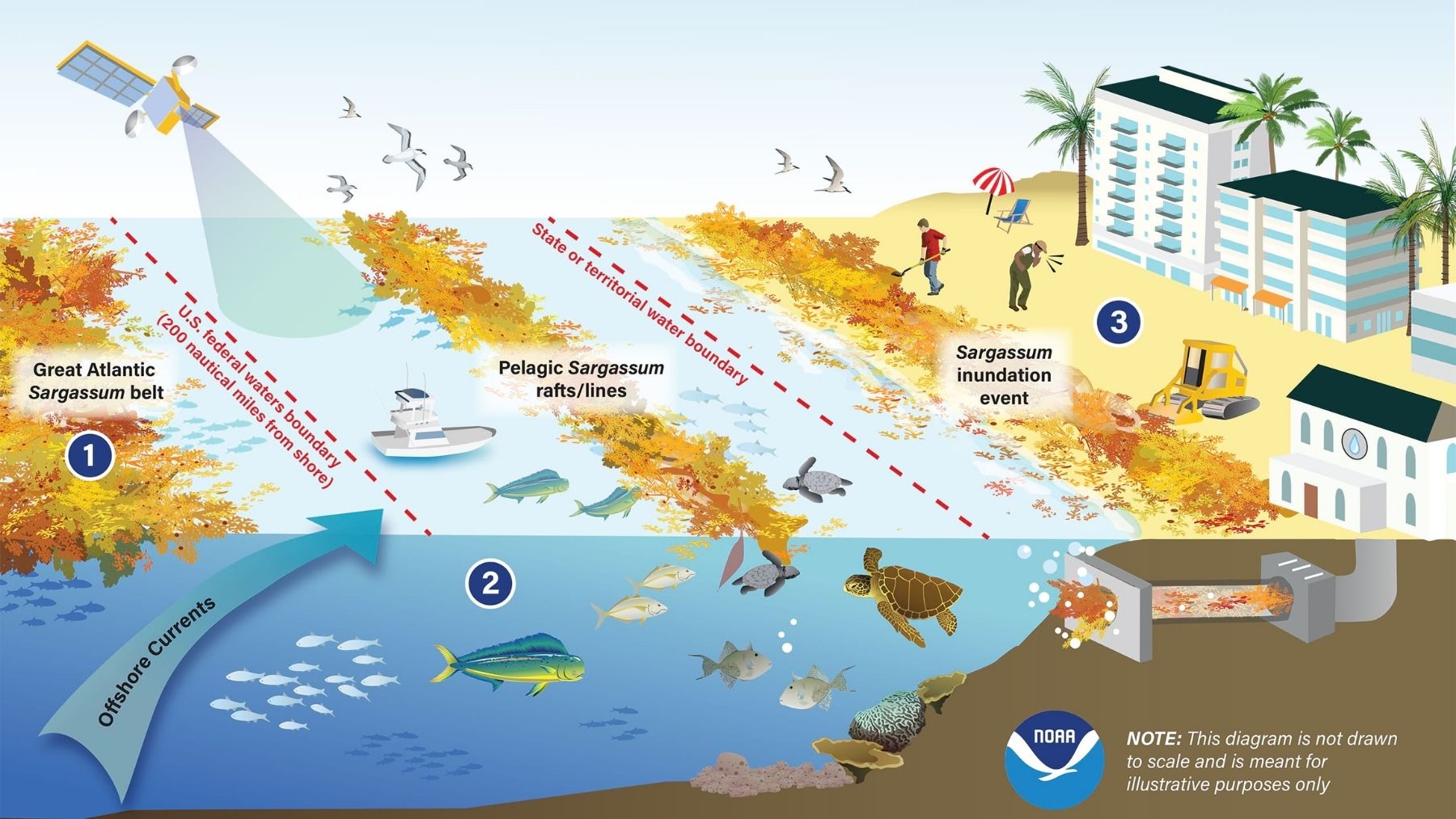

Sargassum is a brown seaweed that floats on the ocean surface like a living raft. For centuries it was mostly known from the Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic, where it drifts in calm, nutrient poor waters and provides shelter for fish, turtles, and other marine life.

That pattern began to change in 2011, when scientists first identified a new band of sargassum forming outside its traditional home. This Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt now stretches from the west coast of Africa across the tropical Atlantic to the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico. It has appeared almost every year since, skipping only 2013, and recent blooms have been the largest ever recorded.

Out in the open ocean, the belt behaves like a moving habitat corridor for wildlife that follow its drifting mats. Closer to shore, though, that same seaweed can pile up in thick, rotting banks that block boats, stress coral reefs, and overwhelm beach towns that depend on tourism.

What the forty year review found

The Harmful Algae review looked at four decades of satellite images, ocean measurements, and nearly nine hundred samples of sargassum tissue. The team compared material collected in the 1980s with samples gathered after 2010 and again after 2020 to see how the seaweed’s chemistry has shifted over time.

Their results show that the seaweed is now loaded with far more nutrients than before. Between the 1980s and recent years, the nitrogen content in sargassum rose by about 55 percent, while the balance between nitrogen and phosphorus increased by roughly half. Phosphorus itself dropped slightly, a sign that the plants are taking up every bit they can find.

To a large extent, that chemical fingerprint points back to land. The review links rising nitrogen to agricultural runoff from fertilizers, wastewater discharges from growing cities, and particles falling in rain and dust from the atmosphere. The authors also connect the first appearance of the belt near the mouth of the Amazon River to nutrient-rich water flowing out during very wet years in the basin.

How the Amazon and pollution feed the seaweed

During the Amazon’s rainy season, huge volumes of river water pour into the Atlantic carrying soil, nutrients, and organic matter from thousands of miles inland. The review finds that sargassum biomass tends to jump after extreme flood years and drop after drought years, suggesting the river is acting like a seasonal fertilizer tap for the open ocean.

Farther north and west, other river systems such as the Mississippi and Atchafalaya also deliver nutrient-rich water to coastal zones. Once there, currents and major flows like the Loop Current and the Gulf Stream can sweep enriched sargassum out into the wider Atlantic, helping to stitch local blooms into a belt that crosses the ocean.

Earlier research in the journal Nature Communications, also involving Florida Atlantic University and partner institutions, had already warned that extra nitrogen from sewage, runoff, and atmospheric inputs was transforming sargassum from a nursery habitat into a large-scale harmful algal bloom. The new review builds on that work and shows that these chemical changes now extend across an entire basin.

From floating habitat to coastal hazard

In moderate amounts, sargassum is a gift for marine life. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration describes it as an essential habitat that supports more than one hundred species of fish and invertebrates, as well as young sea turtles and seabirds that hide and feed among the drifting mats.

Trouble starts when those mats are driven ashore. Beached sargassum quickly begins to rot, stripping oxygen from nearshore waters and releasing hydrogen sulfide, the gas that smells like rotten eggs and can irritate eyes and lungs. Studies also indicate that decomposition releases methane and other gases that add to greenhouse emissions, especially when millions of tons of seaweed collect on hot tropical beaches.

For coastal communities in the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and parts of West Africa, this is no abstract science problem. Families arrive expecting clear blue water and instead find knee deep brown piles buzzing with insects and tangled plastic trash. Clean up costs run into the millions each year, and in 1991 a surge of sargassum in Florida clogged cooling water intakes badly enough to force a temporary shutdown at a nuclear power plant.

What happens next for the Atlantic?

Scientists stress that the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt is the result of both natural ocean dynamics and human influence. Climate patterns can shift winds and currents, pushing surface waters and seaweed into new regions, while land based nutrient pollution gives the plants extra fuel to take advantage of those changes. Lapointe notes that the expansion of sargassum is no longer just an ocean curiosity but a direct challenge for coastal communities.

In practical terms, that means better forecasting and better pollution control have to move together. NOAA and the University of South Florida already maintain satellite-based systems that track the belt and issue weekly risk maps, giving resorts, fishers, and local officials some warning before mats arrive. At the same time, researchers argue that reducing fertilizer runoff, tightening wastewater treatment, and monitoring big rivers like the Amazon will be key to slowing future growth.

No one can say exactly how the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt will evolve over the coming decades, but the new review makes one thing clear. The chemistry of this seaweed now carries the imprint of human activities on land, and the balance of marine ecosystems across the Atlantic is already shifting in response.

The study was published on Harmful Algae.

Image credit: NOAA