Since the James Webb Telescope began operations, the volume of discoveries about the early universe has continued to grow. But even amidst so many surprising revelations, something unexpected caught scientists’ attention: tiny red dots scattered throughout deep space. At first, they seemed like ordinary, distant objects, but as the data accumulated, it became clear there was something very strange about them. Not only were they present in surprising numbers, but they also seemed to disobey some of the rules astronomers knew about galaxy evolution.

Little Red Dots flood the early universe: Why do they vanish so fast?

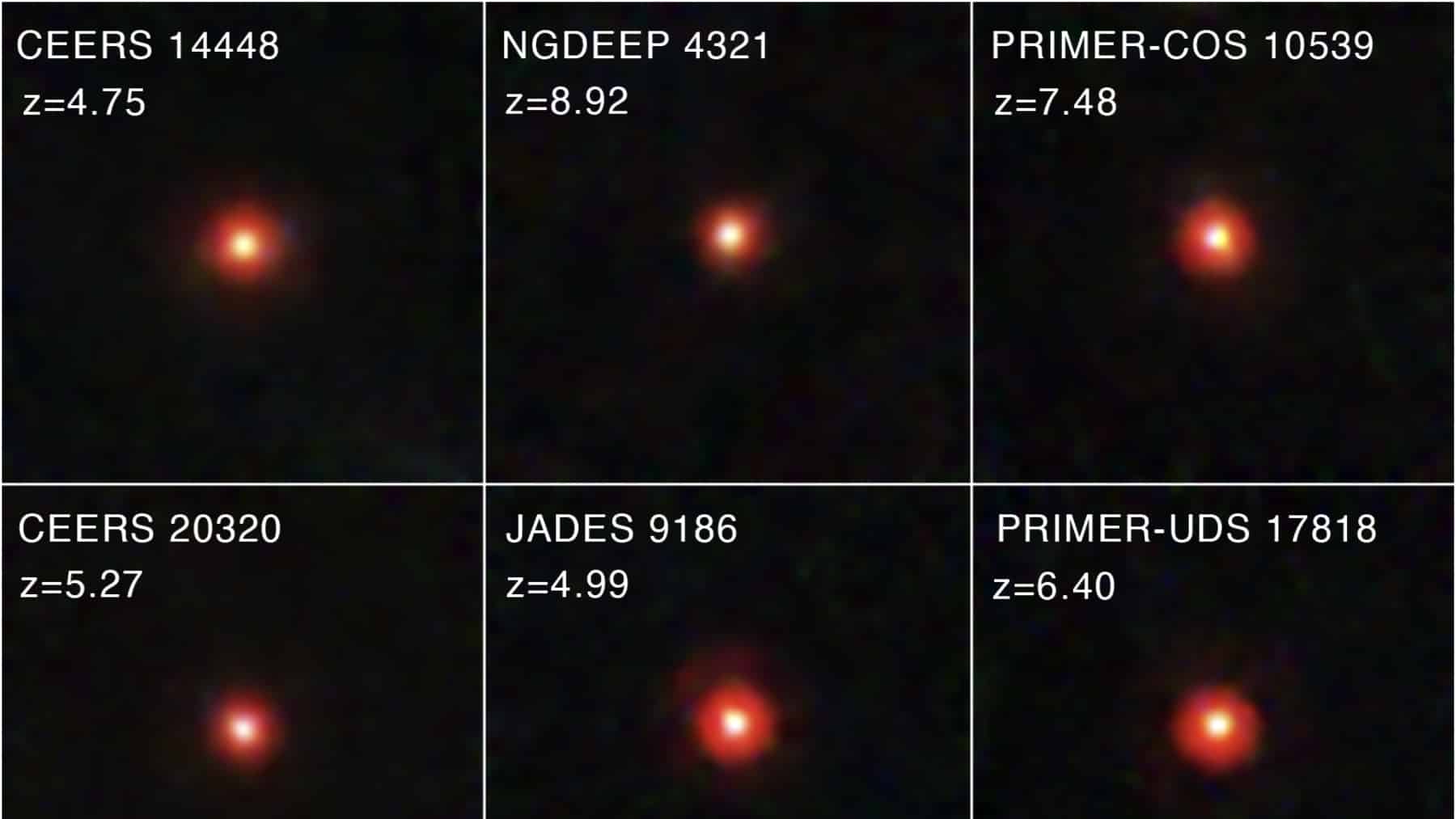

Until analyzing images and spectra from surveys like CEERS, JADES, and NGDEEP, an international team of astronomers began to notice a recurring pattern. Several tiny objects, with whitish cores and diffuse reddish edges, repeatedly appeared in the data; all were very distant, some dating back to when the universe was less than 1 billion years old.

These mysterious galaxies became known as “Little Red Dots” (LRDs), and their frequency was striking: they appear in large numbers about 600 million years after the Big Bang, but disappear around 1.5 billion years later. And this raises the first perplexing question: what exactly are these red dots? Why do they appear only in such a specific time window?

With all the advances in spectroscopic analysis, especially since the RUBIES survey, astronomers have detected something even more intriguing: about 70% of the Little Red Dots (LRDs) showed signs of gas rotating at extremely high speeds, up to 2 million miles per hour. It’s worth noting that this type of movement is typical of accretion disks around supermassive black holes. In other words, perhaps these little red dots are actually galaxies with active black holes growing in their cores, and this changes everything.

Is the early universe hiding a secret black hole boom?

Now, if scientists are right, LRDs would be concrete evidence of a period of accelerated and obscured black hole growth in the early cosmos. In other words, it would be as if the universe were forming giant black holes even before its galaxies were fully developed.

And the most curious thing is that these objects don’t emit much X-ray radiation, which is unusual for active black holes. This may indicate that they are surrounded by dense clouds of gas, which block the emission of high-energy photons, leaving only the infrared light visible, which the Webb telescope can capture (just as it captured more than 800,000 galaxies in the dark).

There’s even a theory under discussion as to why they disappear later: it’s the galaxies’ inward-outward growth. That is, over time, star formation spreads to outer regions, and the black hole is no longer obscured by gas and dust. It “loses” its reddish appearance, becoming blue or neutral, and thus ceases to be an LRD.

The universe didn’t break the rules, we just hadn’t looked deep enough

When LRDs were first observed, some headlines suggested that cosmology was literally broken. After all, if all that light came solely from stars, it would mean that massive galaxies had formed too quickly, which would challenge current models. However, the Webb data indicate otherwise.

This is because most of the light from these objects comes not from stars, but from growing black holes. This changes the scale of these galaxies, making them much smaller and more consistent with what theory predicts. Of course, even so, many questions remain open, and this only shows how science is constantly being revised. And that sometimes, all it takes is a more sensitive look for the universe to reveal its best-kept secrets. It’s no wonder James Webb is making increasingly unimaginable discoveries.