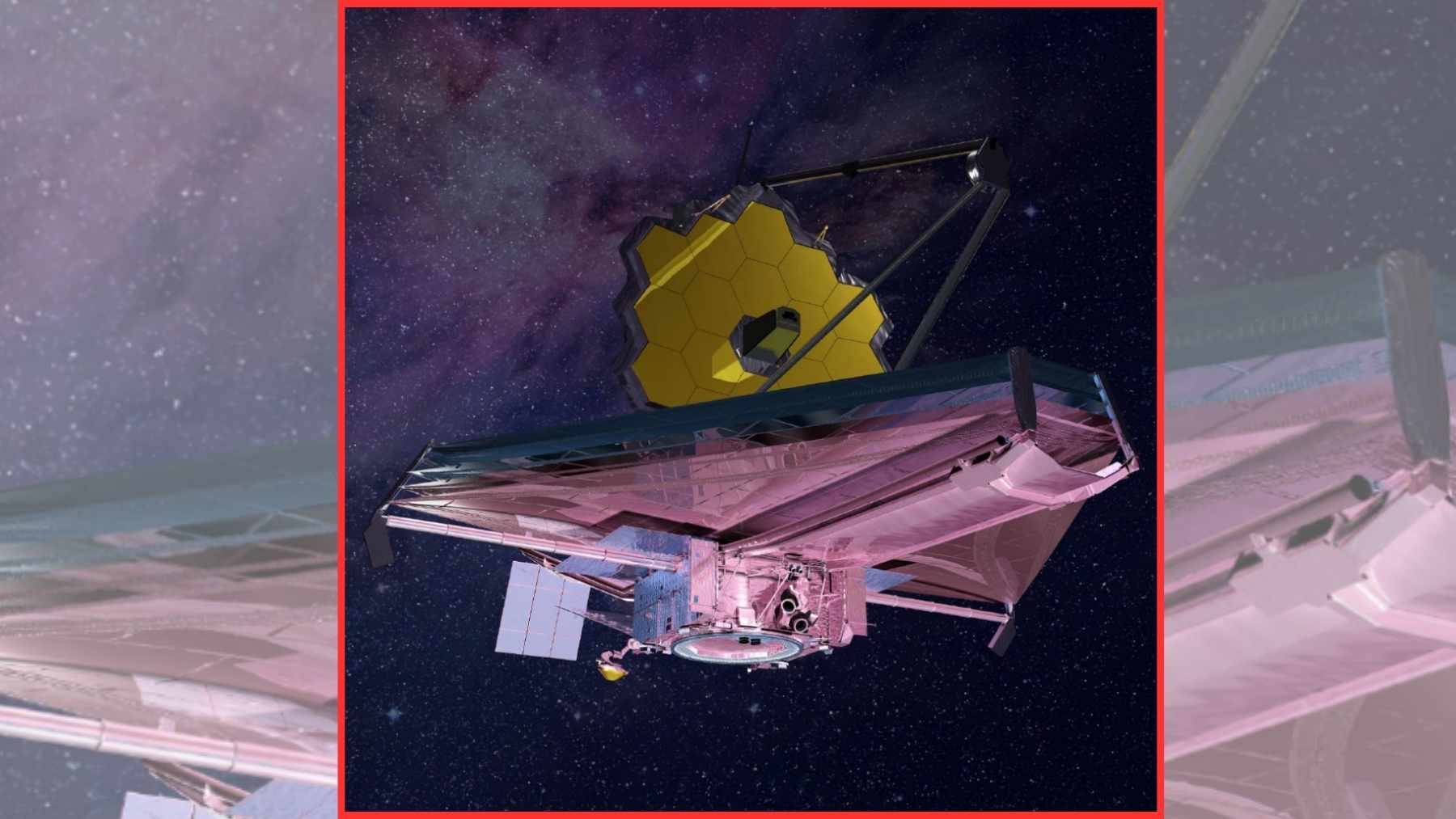

Some 13 billion years ago, a massive star in a tiny young galaxy blew itself apart and briefly outshone everything around it. Now, astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have confirmed that this ancient flash was the earliest supernova ever seen, linked to a powerful gamma ray burst known as GRB 250314A. The explosion happened when the universe was only about 730 million years old, roughly five percent of its current age.

That places the dying star at a redshift of about 7.3, deep inside a period called the epoch of reionization, when the first generations of stars and galaxies were rapidly transforming the cosmos and bathing space in new light. GRB 250314A now holds the record for the most distant confirmed supernova, beating the previous holder that erupted when the universe was already about 1.8 billion years old.

The story started on March 14, 2025, when the French Chinese satellite SVOM detected an intense burst of high-energy radiation from the direction of the constellation Virgo. The event lasted around ten seconds, long enough to identify it as a long gamma ray burst, the type usually tied to the collapse of a massive star into a black hole or a neutron star. Within hours, the Very Large Telescope in Chile measured its extreme distance, marking it as a rare sign of stellar death close to cosmic dawn.

Gamma ray bursts are among the most violent events in the universe. The initial high energy flash fades in seconds or minutes, but it leaves behind an afterglow at X-ray, optical, radio and infrared wavelengths that can linger for days. By studying that fading light, astronomers can work out what kind of catastrophe took place and where it happened. In this case, the afterglow told observers they were looking at something exceptionally distant and powerful.

The crucial step came about 110 days after the burst, when Webb aimed its Near Infrared Camera at the same patch of sky. By then, the afterglow had faded so much that it could not account for all the infrared light that Webb recorded. Astronomers carefully separated the contribution from the faint host galaxy and found an extra glow that matched the expected signature of a supernova. Co-author Antonio Martin Carrillo describes the key evidence as the appearance of a supernova rising at exactly the location of the burst.

To test that idea, the team compared the distant event with well studied explosions in our cosmic neighborhood. Surprisingly, the light curves and spectral properties look very similar to a nearby prototype called SN 1998bw, a supernova long known to be associated with a gamma ray burst. The data also rule out far more extreme possibilities such as a superluminous supernova. In other words, despite erupting in a young, low metal universe, this early massive star seems to have died in a way that resembles modern stellar explosions.

That result challenges a common expectation about the first generations of stars. Many models suggest that early stars, born in nearly pristine gas, should be heavier and more unusual than stars that form today, which might lead to brighter or bluer explosions. GRB 250314A hints that at least some stars in that era behaved much like the massive stars we see now. Lead author Andrew Levan notes that the team was surprised at how well models based on local supernovae matched such a distant event. At the same time, researchers stress that this is only one example and not the final word on early stellar populations.

Webb has also delivered the first clear glimpse of the host galaxy, a compact, star-forming system typical of the reionization epoch. Pinpointing both the galaxy and the supernova gives astronomers a powerful anchor for studying how quickly the cosmos built heavy elements and black holes in its first billion years. The team plans a second round of Webb observations once the supernova has faded by more than two magnitudes, which will let them fully isolate the galaxy’s light and confirm exactly how much came from the explosion itself.

Events like GRB 250314A are more than spectacular fireworks. Supernovae forge and spread many of the heavier elements that later become raw material for planets, atmospheres and eventually living worlds. Without countless ancient stellar deaths enriching space with oxygen, carbon, iron and other ingredients, rocky planets like Earth and the ecosystems that cover them could not exist.

By capturing this record-breaking supernova so close to the beginning of time, Webb has opened a new window on how the universe built the chemistry that later allowed life to emerge. Future bursts and follow-up observations will show whether this ancient star was typical or an outlier. For now, GRB 250314A stands as a reminder that even in the universe’s youth, some stars were already living fast, dying young and seeding space with the building blocks of future worlds.