For decades, the extinction of Gigantopithecus blacki has been one of paleontology’s biggest unsolved stories. This enormous ape, often compared to a real world King Kong, stood close to three meters tall and weighed around 200 to 300 kilograms. Now a large international team has finally pinned down when and why this giant vanished, and their answer carries a clear warning for today’s biodiversity crisis.

Researchers working in southern China combined six different dating techniques on cave sediments and fossils from 22 sites in Guangxi Province. They show that Gigantopithecus disappeared between about 295,000 and 215,000 years ago, after thriving in the region for more than two million years. The team describes this extinction window as the moment when a once successful specialist could no longer cope with a rapidly changing environment.

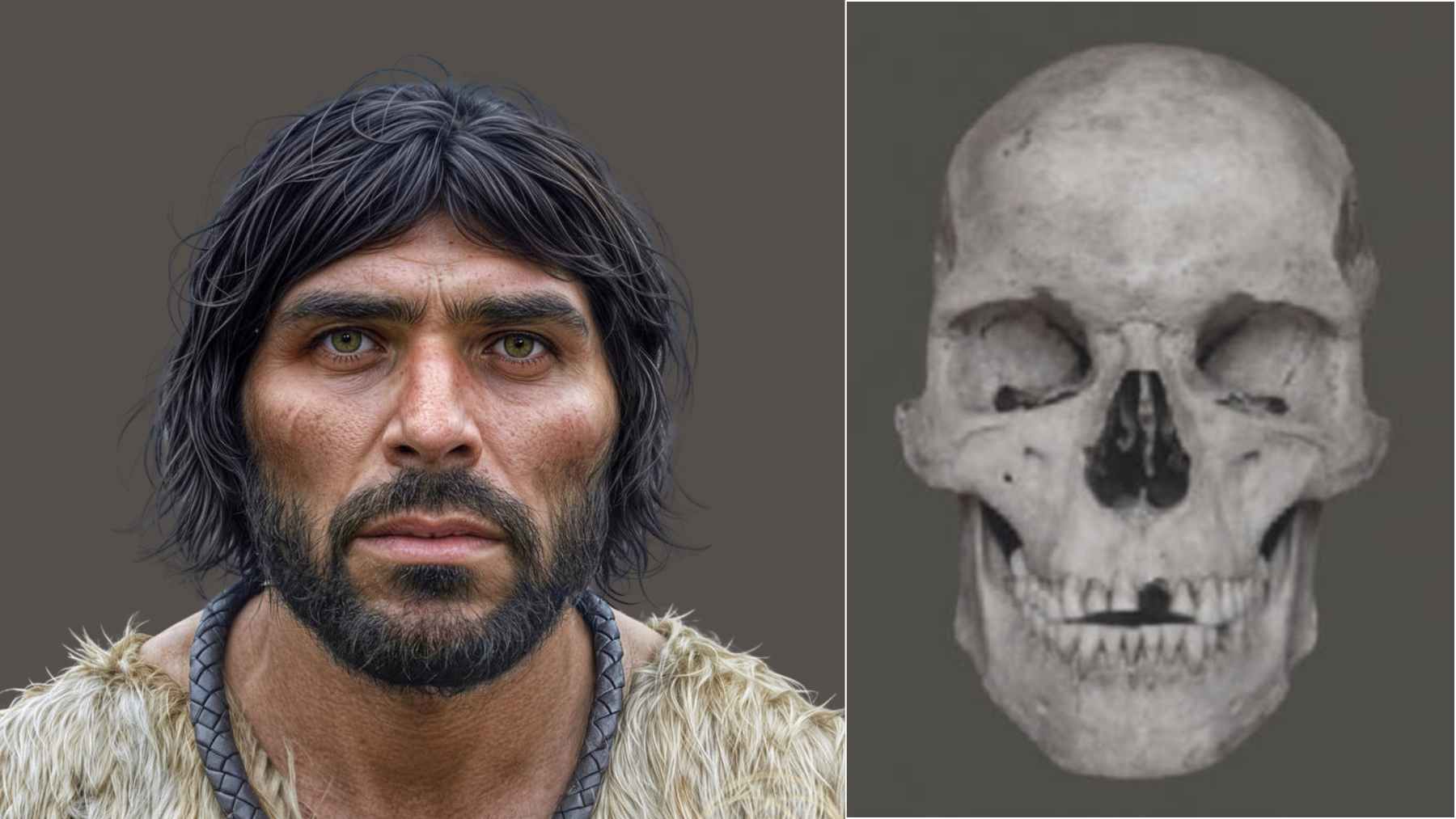

Paleontologist Yingqi Zhang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences calls the mystery of the ape’s disappearance “the Holy Grail in this discipline.” For more than 85 years scientists had only teeth and a few jawbones to work with, plus rough age estimates. Without accurate dates, it was impossible to know whether climate shifts, competition, or early humans were to blame. As geochronologist Kira Westaway explains, “Without robust dating, you are simply looking for clues in the wrong places.”

From forest paradise to stressful home

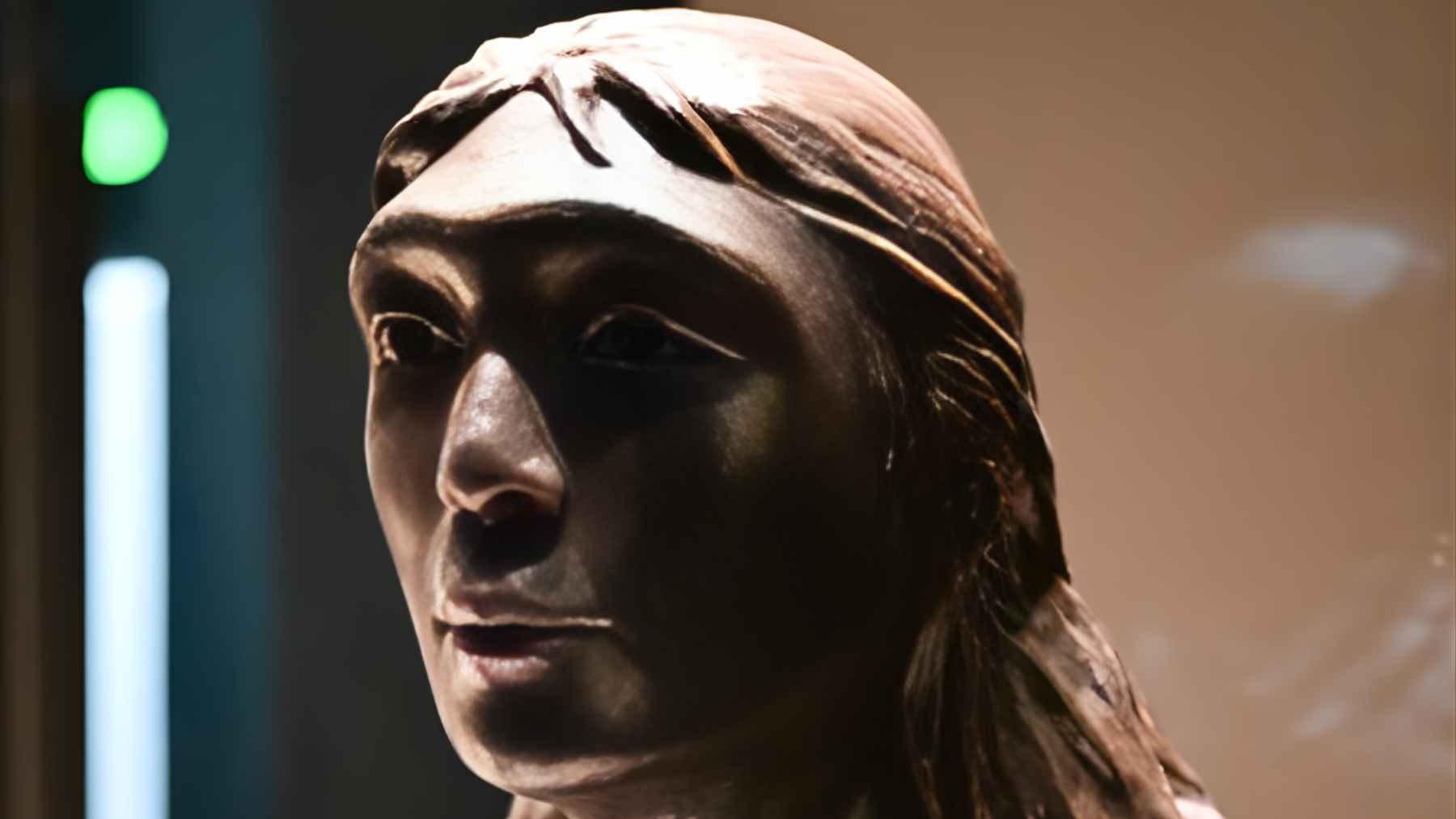

The new study paints a detailed picture of the world Gigantopithecus once occupied. Pollen grains, microcharcoal, fossil animals, and cave sediments reveal that from around 2.3 million years ago the landscape was a rich mosaic of evergreen and deciduous forests mixed with patches of grassland. These productive habitats could support several primate species at once, including the giant ape and its close relative, the orangutan Pongo weidenreichi.

Over time, that balance started to shift. Between roughly 700,000 and 600,000 years ago, the climate in southern China became more seasonal and drier. Forest communities changed, disturbance tolerant plants spread, and forests opened into more mixed woodland and grassland. By about 200,000 years ago arboreal cover had decreased sharply, ferns and grasses expanded, and charcoal levels rose, signaling more frequent fires.

Within this changing landscape, Gigantopithecus began to struggle. The fossil record shows its range shrinking until it survived only in parts of Guangxi. At the same time, the number of Gigantopithecus teeth found in caves drops relative to those of Pongo, a sign that populations of the giant ape were already dwindling.

A specialist trapped by its own body

Dental evidence reveals why the two apes had such different fates. Microwear textures on molars and the chemistry of tooth enamel suggest that both species originally lived in closed canopy forests and relied heavily on fruit, with fibrous plant material as backup food. As fruit became scarcer, Pongo shifted toward a more flexible diet and moved into increasingly open, seasonal habitats.

Gigantopithecus took another route. It remained tied to closed forests and leaned more on tough, low-quality fallback foods. Trace elements in its teeth change from clear, regular bands to blurred, diffuse patterns near the extinction window, which the authors interpret as a signal of long term dietary stress and less reliable access to water. In simple terms, the giant ape was eating enough to survive in the short term but not enough to stay healthy and resilient.

Body size and lifestyle added to the problem. Gigantopithecus was exclusively terrestrial, massive, and probably slow moving. That combination meant higher energy demands, reduced mobility, and likely lower reproduction rates compared with lighter, more agile orangutans. When forests became patchier and more open, this specialist could not easily track resources across the landscape.

No human culprit, only climate and rigidity

One striking conclusion of the study is what did not happen. Unlike many later megafaunal extinctions in Australia and the Americas, there is no evidence that humans or archaic hominins played a role in wiping out Gigantopithecus. The species vanished long before our own kind transformed ecosystems across Southeast Asia.

Instead, the giant ape’s fate was sealed by increasing environmental variability combined with an inflexible way of life. As the authors put it, Gigantopithecus was the “ultimate specialist.” That strategy worked as long as evergreen forests stayed stable. Once those forests began to fragment and change, the very traits that made the ape impressive became liabilities.

Lessons for a sixth mass extinction

The story of Gigantopithecus is not just a prehistoric curiosity. Large animals today face similar pressures from rapid climate shifts, habitat fragmentation, and the loss of key food sources. Species that depend on narrow diets or specific habitats, such as many great apes, are especially vulnerable.

Westaway notes that with a potential sixth mass extinction on the horizon, understanding past losses is essential to predicting which species are most at risk now. The demise of this giant ape shows that even dominant animals can disappear quickly when environments change faster than they can adapt.

In the end, Gigantopithecus did not vanish overnight. It endured millions of years in Asian forests, then slowly faded as its world dried, opened, and burned. Its teeth record that long struggle in microscopic scars and chemical traces. For modern conservation, those ancient signals are a reminder that survival belongs not to the biggest, but to the most adaptable.