When water runs low in Panama, the whole world feels it. The Panama Canal handles roughly 5% of global maritime trade, so every ship that has to wait or reroute means more fuel burned, higher freight costs, and, eventually, pricier goods on store shelves.

Over the last two years, an unusual combination of El Niño and global warming has pushed the canal into a prolonged drought. Water levels in Gatún Lake, the freshwater reservoir that feeds the locks, fell to record January lows in 2024, almost six feet below the previous year.

Canal authorities cut daily transits from a typical 38 ships to about 24 and imposed draft limits, a change that led to long queues and some vessels detouring thousands of extra miles.

A recent climate study suggests that under high greenhouse gas emissions, these low water conditions could become much more common by the end of the century. The work, published in Geophysical Research Letters, finds that extreme low levels in Gatún Lake like those seen in 2016 could become roughly twice as likely if warming continues unchecked.

Each full canal transit already uses around 50 million gallons of fresh water, and the canal’s daily operation consumes about two and a half times as much water as New York City.

So global shipping is looking for safety valves. That is where southern Mexico comes in.

A rail bridge between the Pacific and the Gulf

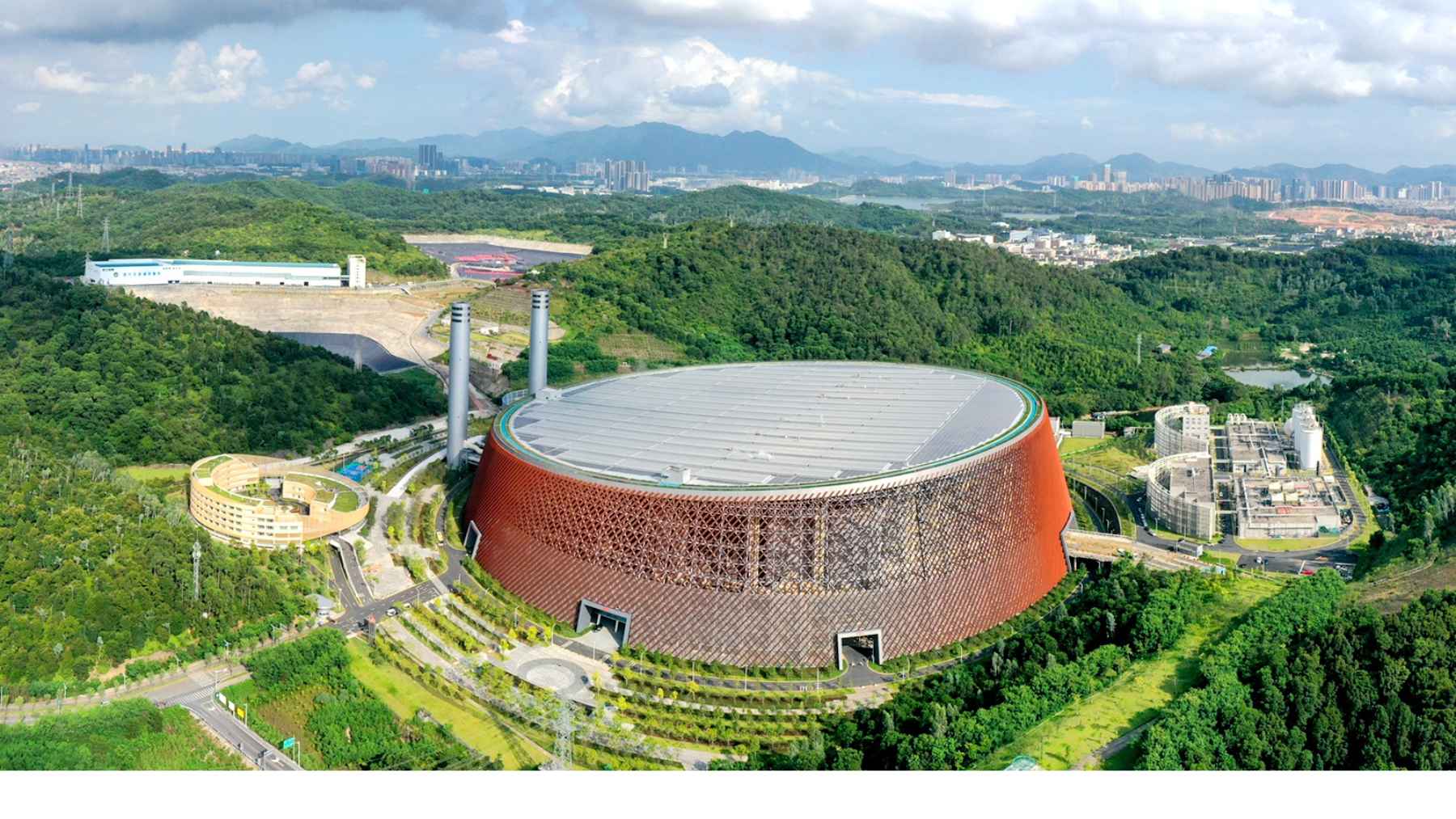

Mexico’s Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, known as CIIT, cuts across one of the narrowest parts of the country. The project links the Pacific port of Salina Cruz in Oaxaca with Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf of Mexico using a 303 kilometer freight and passenger railway, expanded ports, highways, energy infrastructure, and planned industrial parks along the route.

The corridor is managed by the Mexican Navy and was formally approved in 2019. Rail freight service on the main line began in 2023, and the government now expects the wider logistics platform to be fully completed around mid-2026.

Officials and industry groups present it as a modern “dry canal” that can connect Asia to the eastern United States or Europe without depending on Panama’s water levels.

In practical terms, cargo arrives by ship on one coast, travels across the isthmus by train, then continues by sea from the opposite coast. For shippers, what matters is how long that whole zigzag takes.

A 72-hour test run

In spring 2025, Hyundai and its logistics arm Hyundai Glovis put the corridor to the test. The car carrier Glovis Cosmos delivered about 900 vehicles from Asia to Salina Cruz. They were loaded onto special Bi Max rail wagons, moved across Mexico to Coatzacoalcos in a roughly nine-hour train journey, then reloaded onto the vessel RCC Africa for the final leg to the United States east coast.

Mexican and logistics media report that the full ocean-to-ocean operation is being benchmarked at about 72 hours of transit between the two coasts for this type of shipment, compared with 15 to 20 days for some Panama Canal routes under drought-related restrictions.

For automakers, shaving that much time off a route can mean fewer cars sitting idle and a smoother supply of vehicles to dealerships.

It is easy to see the appeal when you imagine cars stuck on a ship, waiting for a canal slot, while demand on the showroom floor keeps rising.

Climate, CO2 and shifting risks

From a climate point of view, the story is more nuanced. Drought in Panama has already cut transits by about 30% and forced some ships to reroute around South America, which adds days at sea and extra emissions. A stable rail bridge that shortens certain routes could, in theory, help avoid some of that detouring and the fuel that goes with it.

At the same time, the CIIT is not just a railway. It includes ten planned industrial parks and new energy and road infrastructure in a region that still holds significant tropical forests and coastal ecosystems.

Environmental and Indigenous groups warn that without strict safeguards, the corridor could accelerate deforestation, fragment habitats, and increase pollution around communities that are already vulnerable to climate impacts.

So the project sits at a crossroads of climate adaptation and new pressure on local environments.

Communities and safety in the spotlight

Social tensions around the CIIT did not start with the Hyundai train. For several years, Indigenous communities in Oaxaca and Veracruz have protested land sales for industrial parks, criticized environmental impact studies, and in some cases won court rulings that temporarily halted construction.

Then, in late December 2025, a passenger service on the Interoceanic Train derailed in the state of Oaxaca, killing more than a dozen people and injuring many others.

The accident triggered calls in Mexico’s Congress for investigations into alleged irregularities in construction contracts and raised questions about safety oversight on flagship rail megaprojects operated by the military.

For residents along the tracks, the promise of jobs and better infrastructure now coexists with grief and concern over how quickly the project has moved and how transparently it has been managed.

Two corridors, one shared challenge

At the end of the day, the Panama Canal and Mexico’s dry canal are reacting to the same pressure. Warmer temperatures disturb rainfall patterns, stress water reserves, and push governments and companies to bet on big, complex infrastructure in search of stability.

Whether the CIIT becomes a lasting complement to the Panama Canal or remains a niche route will depend on more than transit times.

Its long-term credibility will hinge on cutting its own carbon footprint, protecting ecosystems on the Isthmus, and ensuring that Indigenous and local communities have a real say in how the project evolves.

The Panama climate study that highlighted growing drought risks for the canal was published in Geophysical Research Letters.