For four decades, the Pacific coast of Panama has counted on a reliable seasonal pulse of cold, nutrient-rich water that powers local fisheries and cools coral reefs. In early 2025 that pulse all but vanished. Scientists report that the Gulf of Panama’s usual upwelling failed for the first time in the instrumental record, a breakdown they see as a warning about how quickly climate disruption can unsettle tropical seas.

During most years from roughly December to April, strong northerly trade winds sweep across Central America and into the Gulf of Panama. Those winds push aside warm surface waters so that cooler deep water can rise, bringing nutrients that feed phytoplankton and, in turn, dense schools of fish. The same cool water takes the edge off regional marine heat, giving nearby coral reefs a measure of protection against bleaching during the dry season.

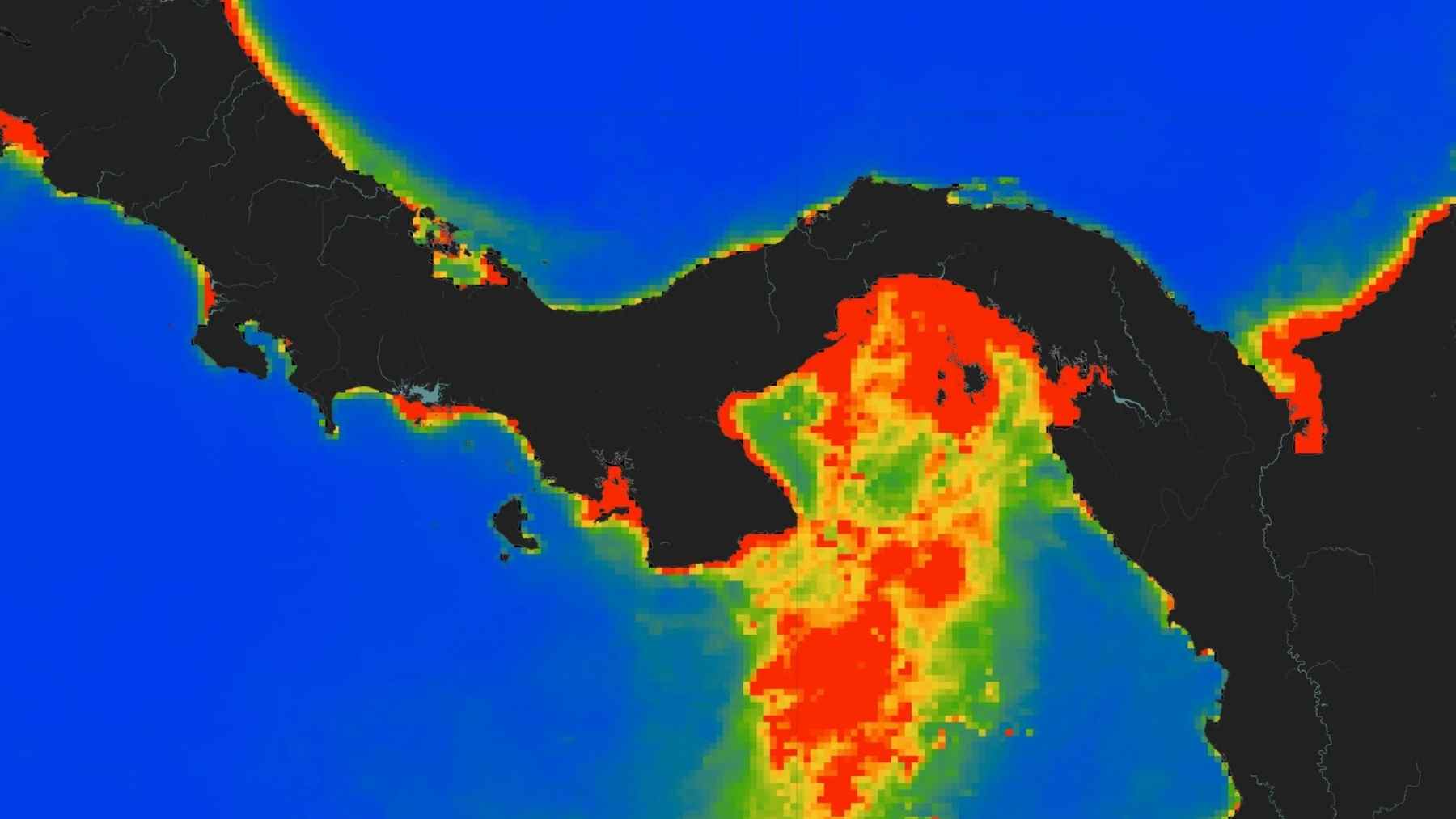

The 2025 season looked very different. Satellite maps that usually glow red over the gulf at the height of upwelling instead showed extremely low chlorophyll, a sign of a depleted surface ocean. Field measurements revealed that the water column remained strongly stratified, with little sign of the vertical mixing that normally defines this system.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study found that typical upwelling in the region begins in late January, lasts about two months and can drive surface temperatures down near nineteen degrees Celsius, while in 2025 cooling arrived weeks late, persisted for only a short period and never reached past about twenty three degrees.

Biologist Aaron O’Dea of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) described the scene bluntly, saying that “the tropical Panamanian sea has lost its vital breath.”

What robbed the ocean of that breath was not a lack of cold water at depth but a breakdown of the atmospheric engine that normally lifts it. The research team shows that in 2025 the Panama wind jet formed far less often than usual, so the cumulative push of northerly winds never reached the threshold needed to trigger robust upwelling. When those winds did blow they were about as strong as in past years, yet their frequency dropped sharply and calm periods lengthened, leaving surface waters warm and stratified.

“For the first time, we have observed how changes in an atmospheric and oceanic circulation system exceed a threshold and lead to reduced biological production,” explained Ralf Schiebel of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry. At the same time, climate geochemist Gerald Haug cautioned that it is still too early to state that warming alone will systematically weaken this tropical upwelling, even though the event fits broader concerns about shifting wind patterns in a hotter world.

The ecological fallout in the gulf has been rapid. With few nutrients reaching the surface, phytoplankton populations shrank and the base of the food web weakened. Reports from the region describe sharp drops in the availability of small pelagic fish such as mackerel and sardines along with squid and other cephalopods.

Coral reefs, which usually benefit from cooler upwelled water, endured more intense heat stress, increasing the risk and severity of bleaching events. The study warns that repeated failures of upwelling could drive long term declines in fisheries productivity and amplify thermal stress on already vulnerable coral communities.

For coastal villages and small-scale fishers around the Gulf of Panama, this is not an abstract oceanographic anomaly. Their catches depend on the seasonal enrichment that upwelling brings, and any sustained drop in productivity threatens incomes and local food security. Scientists involved in the work emphasize that the same physical process that fertilizes the sea has supported human societies along this coast for centuries.

The 2025 failure also exposes a quiet gap in global climate monitoring. Temperate upwelling systems off California or Peru are tracked closely, but many tropical counterparts are sparsely instrumented. Apart from a forty-year satellite record and a handful of coastal stations, the detailed picture in Panama existed only because the research yacht S Y Eugen Seibold had begun systematic surveys in the region two years earlier.

“If our oceanographic mission had not taken place, no one would have known the upwelling had stopped,” noted researcher Hanno A Slagter. That prospect worries scientists, because similar breakdowns in other poorly monitored tropical regions could unfold without any warning for managers, fishers or coastal communities.

The authors of the PNAS paper argue that the Panama event should be treated as an early test of resilience for tropical oceans. Whether 2025 turns out to be a rare outlier or the first in a series of failed seasons will depend on how trade winds, large-scale climate patterns and greenhouse gas emissions evolve over the coming years.

What is already clear is that communities and ecosystems have grown tightly bound to a seasonal rhythm in the sea that is less guaranteed than it once seemed. Strengthening ocean observing networks, updating fisheries management and accelerating efforts to limit global warming are all part of the response if we hope to keep that rhythm alive.

Image credit: Aaron O’Dea.