The platypus already looks like an animal assembled from spare parts, with a duck-like bill, webbed feet, and a beaver-style tail. On top of that, adult males carry a hidden weapon on each hind leg: a spur that can inject venom strong enough to send a healthy adult to the emergency room. People stung describe pain that feels wildly out of proportion to the tiny wounds on their skin.

Doctors and biologists have spent decades trying to understand what makes this venom so unusual and why no one has created an antivenom for it. Recent clinical reports from Australia and detailed lab work on the venom’s chemistry suggest an answer: the platypus produces a rare, complex mix of molecules that cause intense, long-lasting pain, but cases are so uncommon that large scale antivenom development simply does not make sense.

A rare venom hidden in the platypus’s hind legs

Only male platypuses are venomous, and their venom comes from a hard spur on each back leg connected to a gland in the upper thigh. The gland grows and becomes active during the breeding season, when males compete with one another, and then shrinks again as the season ends. That timing has led researchers to see the venom mainly as a weapon in fights over territory and mates, not as a way to catch food.

When two males wrestle in a stream or riverbank, a well placed kick lets one animal hook its spur into the other’s skin. The leg can twist so the spur works like a tiny switchblade, and venom travels down a narrow duct from the gland straight into the wound. Young males grow small spurs too, but until they reach sexual maturity the glands produce little to no venom, which fits the idea that this system evolved for adult social battles.

Why a platypus sting hurts so much

People who have been stung describe almost the same story every time. The pain starts immediately, builds quickly, and then just keeps going. Swelling spreads well beyond the puncture marks, and the injured hand or foot can become so sensitive that even a light touch or the weight of a bedsheet feels unbearable. In classic case reports from Australia, standard painkillers did almost nothing, and some patients needed strong nerve blocks just to cope.

The main reason, scientists say, is that platypus venom seems tuned to crank up pain nerves rather than shut down the heart or lungs. Laboratory work led by Glenn de Plater at the University of Sydney showed that the venom acts directly on nerve cells involved in pain, while a special hormone-like component called a natriuretic peptide triggers immune cells that add to the inflammation and throbbing. Other research on venoms more broadly suggests these substances likely flip on channels in nerve membranes that act like tiny electrical gates, so once they are open, the pain signal just keeps firing.

Inside the cocktail of platypus venom

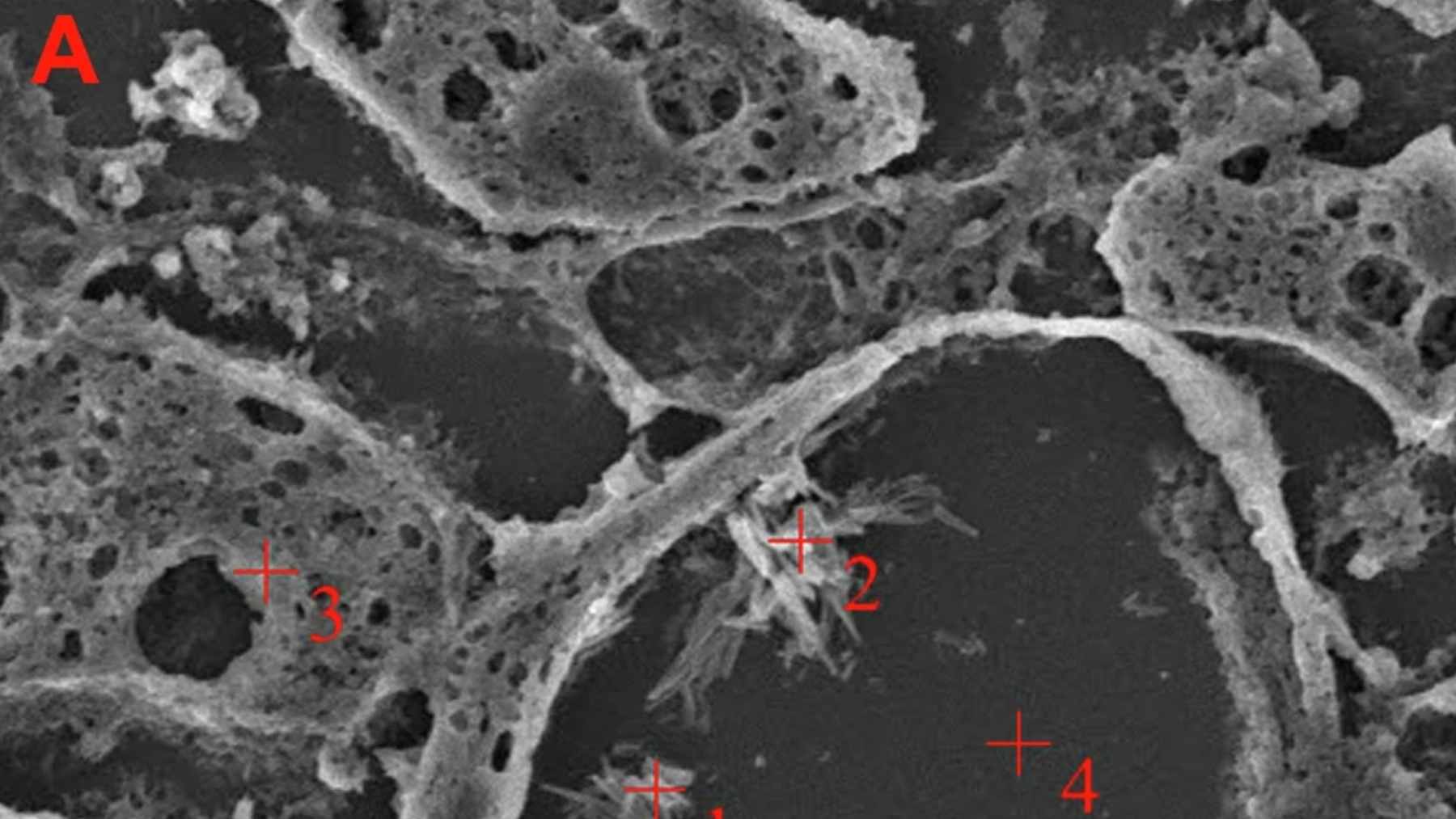

Chemically, platypus venom is not a single toxin but a crowded mix of small proteins called peptides. A team led by Anthony Torres at the University of Sydney showed that several of these peptides belong to a group known as defensin like peptides, which normally help the immune system fight germs but in the platypus have been retooled into weapons that damage or excite cells. Using high resolution imaging techniques, they mapped the three dimensional shape of one of these peptides and found it resembled toxins from sea anemones, hinting at deep evolutionary links between very distant animals.

Another key step came from Masaki Kita and colleagues at the University of Tsukuba, who reported in the Journal of the American Chemical Society that platypus venom peptides trigger a rush of calcium into nerve like cells grown in the lab, a classic sign that those cells are being powerfully activated. Later genetic and protein studies led by Camilla Whittington at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSTL) and partners in Australia uncovered dozens of venom related genes, including ones for natriuretic peptides and a nerve growth factor that seem to appear only in this mammal’s venom gland.

If it hurts, why is there no antivenom?

Given how extreme the pain can be, it might seem surprising that no one has made an antivenom for platypus stings. The first reason is simple: cases are very rare. Platypuses live only in certain parts of eastern Australia and Tasmania, and they are protected wildlife, so most people never touch one at all. Doctors in the Medical Journal of Australia point out that serious envenomations show up in emergency departments only occasionally, especially when compared with snake or spider bites, which can be life threatening.

There is also the problem of complexity. To build a useful antivenom, producers would need to raise antibodies against many different platypus peptides and prove that this mixture actually shortens pain and limits tissue damage. That is expensive, slow work, and early case reports suggest most patients recover with careful wound cleaning, strong pain relief, and time, even if that time can feel endless to the person who cannot grip a coffee mug with their injured hand. Toxicology specialists have therefore argued that research dollars are better spent improving pain management guidelines than chasing a custom antivenom that few hospitals would ever use.

From painful sting to possible new medicines

For drug developers, the same features that make platypus venom a nightmare in the moment make it a fascinating toolkit. Peptides that can dial nerve activity up so precisely might one day inspire medicines that dial it down in people living with chronic pain, by blocking the same pathways or by using modified versions of the venom molecules in a controlled way. Studies of venom derived nerve growth factor and related compounds have already raised the possibility of using them to study nerve repair and sensitivity, especially in conditions where everyday sensations feel painfully amplified.

At the end of the day, most of us will only ever see a platypus on a screen or behind glass, not in a riverbank tussle. Even so, this quiet, secretive animal is helping scientists piece together how mammalian venom evolves, how pain circuits behave, and how new treatments might be built from some very old survival tricks. The main recent clinical study on human platypus envenomation has been published in the Medical Journal of Australia.