Far off the Dutch coast, something unexpected is taking shape beneath the future towers of a massive offshore wind farm. Concrete blocks called Reef Cubes are being lined up around turbine foundations, turning what was once a flat, almost empty seabed into a place where marine life can hide, feed, and grow.

The project, known as OranjeWind offshore wind farm, will be built by German utility RWE and French energy company TotalEnergies in the Dutch North Sea. Once construction is finished, 66 Reef Cubes supplied by UK eco‑engineering firm ARC Marine will be placed around 11 turbines, creating about 1,440 square meters of new hard surface for life to colonize. At the end of the day, this clean energy project is designed to produce two outputs at once: electricity for homes and fresh habitat for the sea.

A seafloor built for stability, not for life

Traditional offshore wind sites are chosen for their engineering qualities, such as stable sediments and enough depth for shipping lanes, not for rich ecosystems. Foundations are anchored in the seabed and then wrapped in layers of rock known as scour protection, which keeps strong currents from washing sand away from the base of each tower.

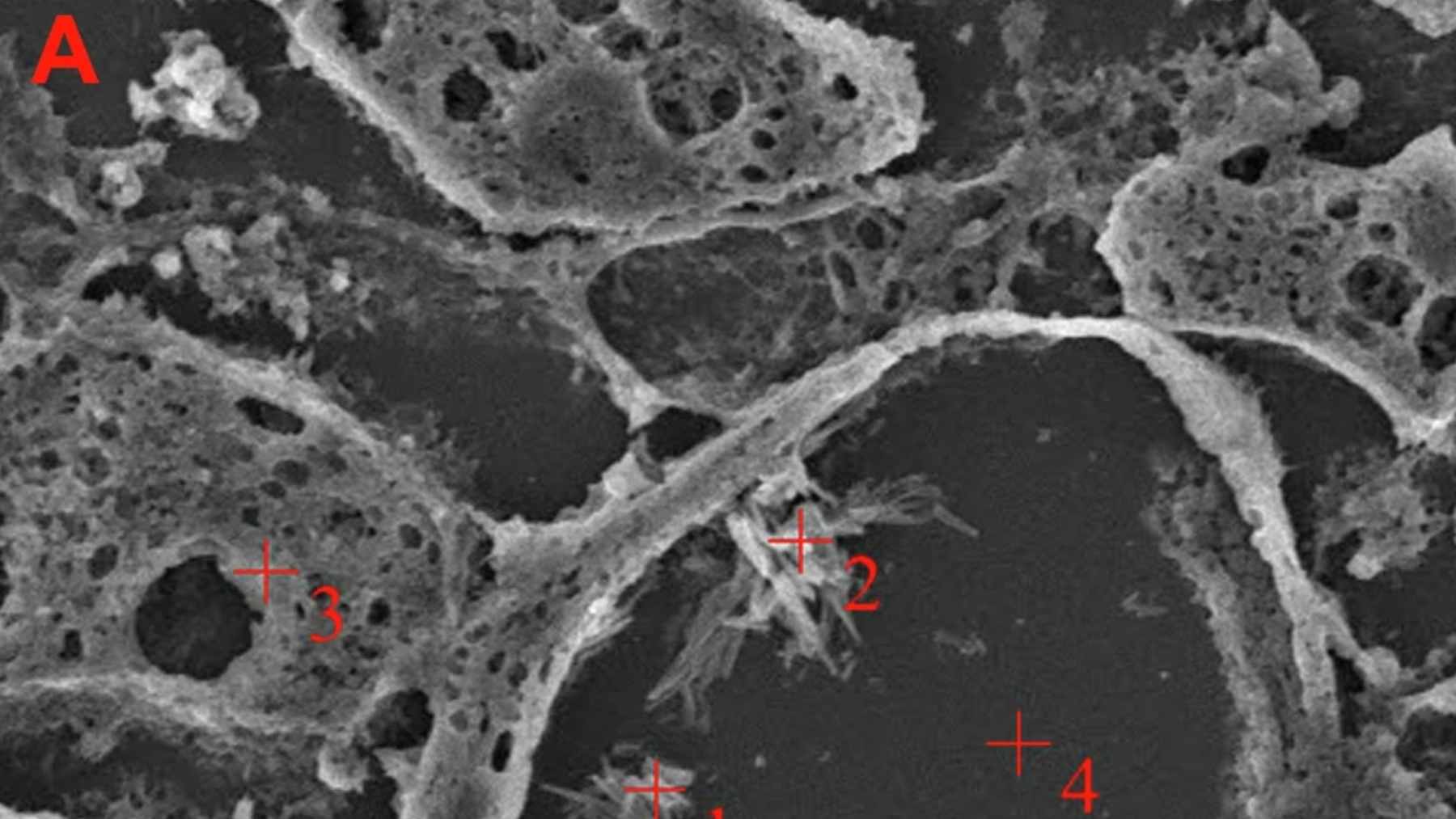

That setup is safe for turbines but offers little for marine life beyond a rough rock blanket. There are few overhangs, no sheltered chambers, and not much variation in height, so smaller organisms have fewer places to attach or hide. Scientists who study artificial reefs often say that without complexity, many creatures simply pass through rather than settle.

How Reef Cubes turn turbine bases into reefs

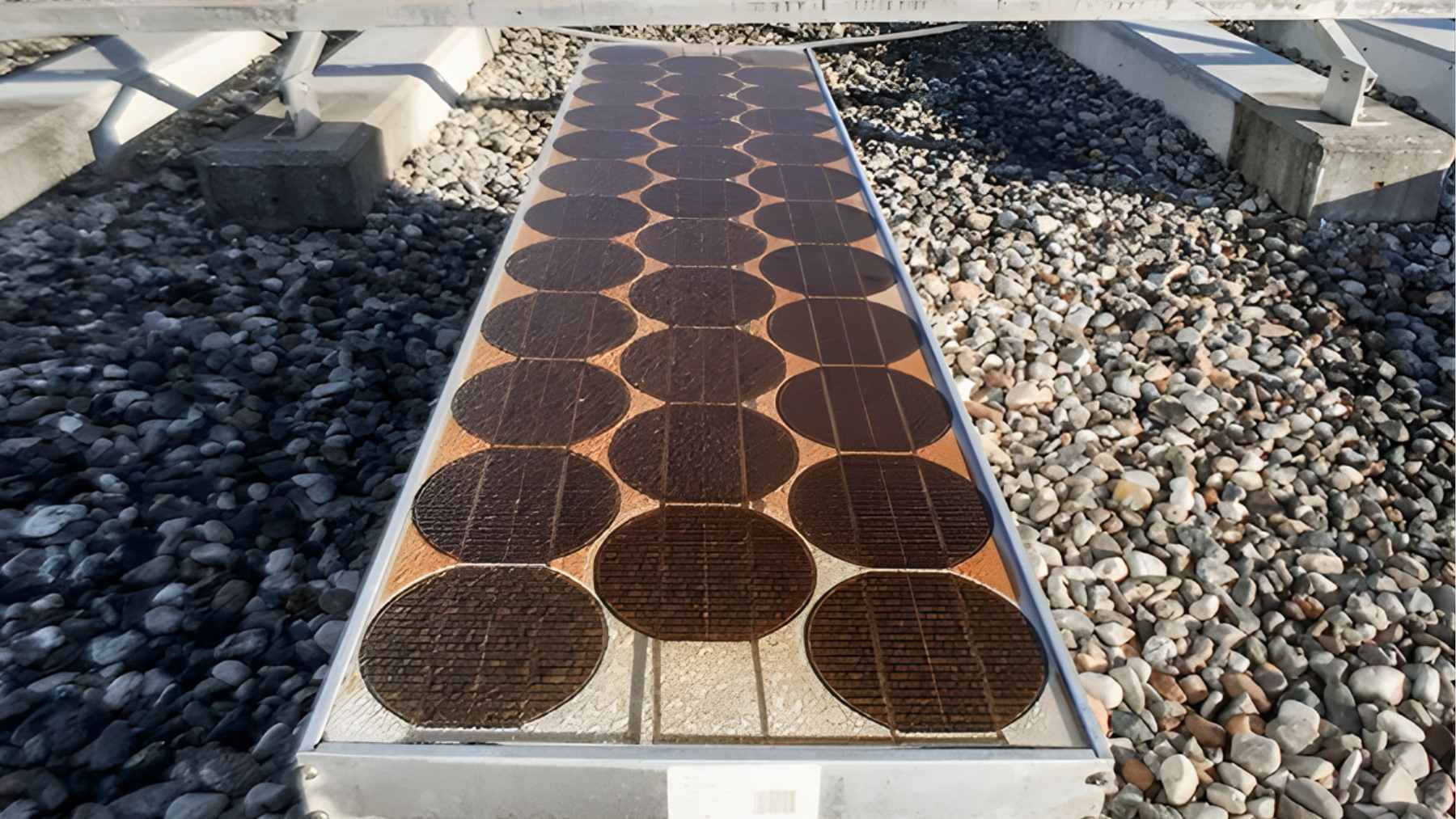

Reef Cubes are engineered blocks of low‑carbon, recycled concrete that look a bit like oversized dice, each with a hollow central chamber and openings on every side. At OranjeWind, each unit is about 1.5 meters high, weighs nearly six tons, and is certified as safe for the marine environment, with crushed shell in the mix to encourage native oyster larvae to attach.

Instead of replacing the existing rock, the cubes will sit on top of the scour protection around selected turbines. Their stacked faces, rough textures, and internal cavities slow the flow of water and create shaded pockets where sediment and nutrients can settle rather than being swept away. In practical terms, that means more nooks and crannies where algae, worms, and shellfish can get a foothold.

Tom Birbeck, chief executive of ARC Marine, said the OranjeWind order “marks the transition from pilot to full commercial delivery” of this kind of nature‑inclusive reef design. The cubes are expected to stay in place for the full operational life of the wind farm, providing long‑term habitat rather than a short‑term experiment.

How marine life responds when structure appears

Nature rarely waits for a ribbon‑cutting. As soon as hard surfaces appear in moving water, tiny organisms such as algae, larvae, and sponges begin to settle, forming a thin living film that gradually thickens into a community. Over time, shellfish, anemones, and seaweeds can cover the concrete, and fish start using the new spaces as shelter and hunting grounds.

Earlier trials with Reef Cubes in the North Sea, including a dedicated test site run with Dutch program The Rich North Sea, have already shown this pattern. Divers and underwater cameras recorded crabs, starfish, anemones, and shoals of small fish weaving in and out of the blocks once they had been in the water for a while.

RWE’s press material explains that at OranjeWind, cod and native oysters have been chosen as focal species because of their wider ecological importance in the North Sea. If the cubes offer enough shelter and food, these species can help rebuild a more complex food web around the turbine bases instead of leaving them as simple industrial structures.

Clean energy that tries to repair the ocean too

The OranjeWind plan builds on earlier work at the Rampion offshore wind farm in the United Kingdom, where around 75,000 Reef Cubes were installed as part of a pilot called Reef Enhancement for Scour Protection. There, the cubes were used not only to protect turbine foundations from erosion but also to test how well they could function as long‑term artificial reef systems.

Experts involved in these projects argue that design choices at the base of a turbine can make the difference between a lifeless patch of rock and a thriving micro‑reef. As ARC Marine scientist Sam Hickling told one engineering publication, “the main idea to incorporate into the design of an effective artificial reef is the complexity of the habitat.” In other words, if offshore wind is already reshaping the seafloor, planners can decide whether that change is neutral or actively helpful for biodiversity.

For most of us, offshore wind shows up only as a line on the electric bill or a distant row of blades on the horizon. Underneath, projects like OranjeWind hint at a future where climate solutions and ecosystem repair happen in the same footprint instead of competing for space.

The official press release was published on the RWE website.