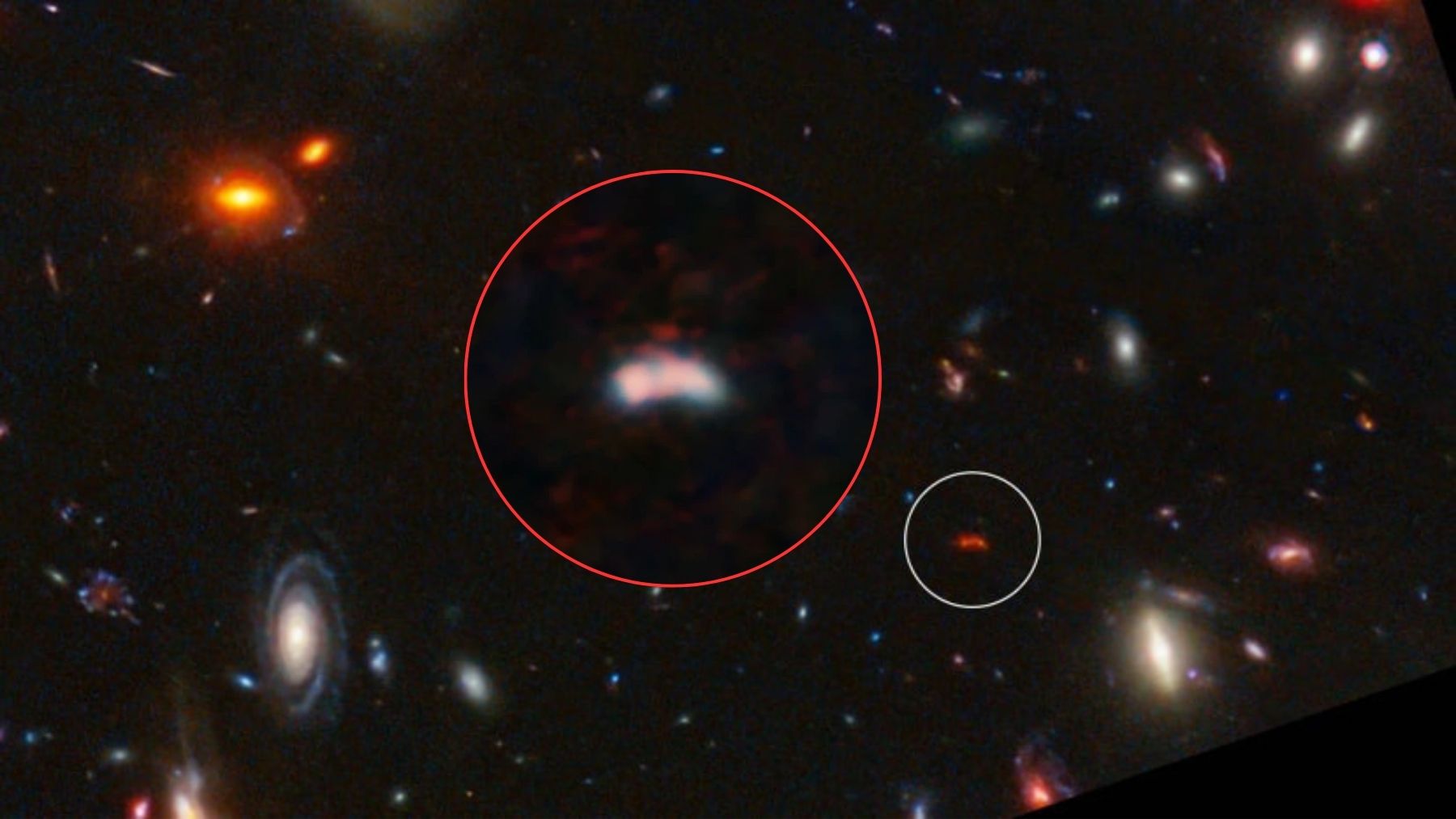

Imagine a single galaxy churning out newborn suns 180 times faster than the Milky Way. Now place it in the young universe, only about 600 million years after the Big Bang. That is what astronomers have found in galaxy Y1, an ultraluminous infrared “star factory” wrapped in superheated dust and spotted with the ALMA telescope.

Galaxy Y1 and its extreme distance

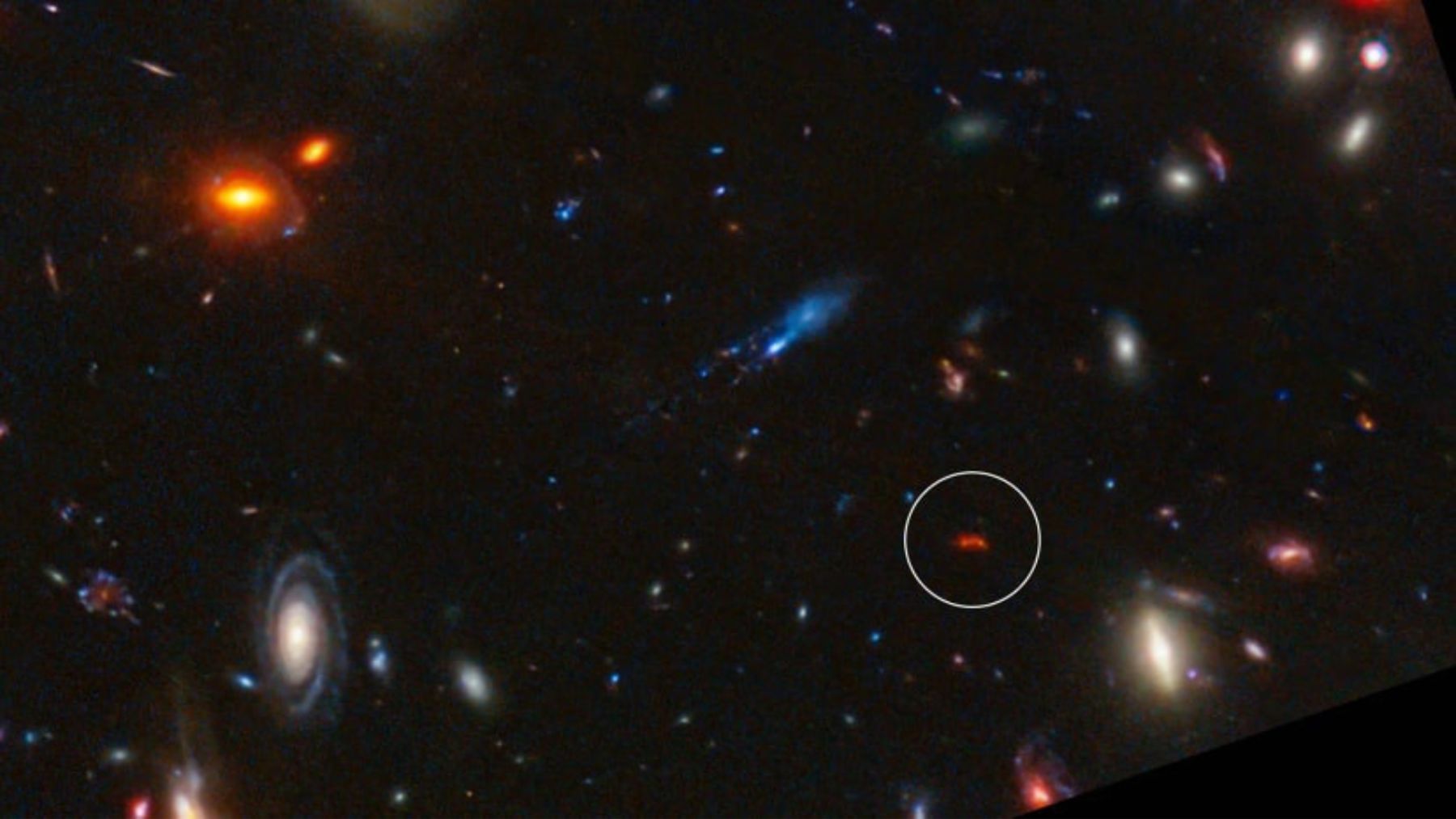

Y1, formally known as MACS0416_Y1, is so remote that its light has taken more than 13 billion years to reach Earth. It sits behind a massive cluster of galaxies called MACS0416 in the constellation Eridanus, its light stretched by cosmic expansion to a redshift of about 8.3. That natural magnification helped astronomers turn this faint smudge into a detailed laboratory of early galaxy growth.

Lead author Tom Bakx of Chalmers University describes it simply. The team is “looking back to a time when the universe was making stars much faster than today,” a time when conditions were harsher and gas was denser than anything we see in the Milky Way’s quiet neighborhoods.

Star factories and cosmic dust

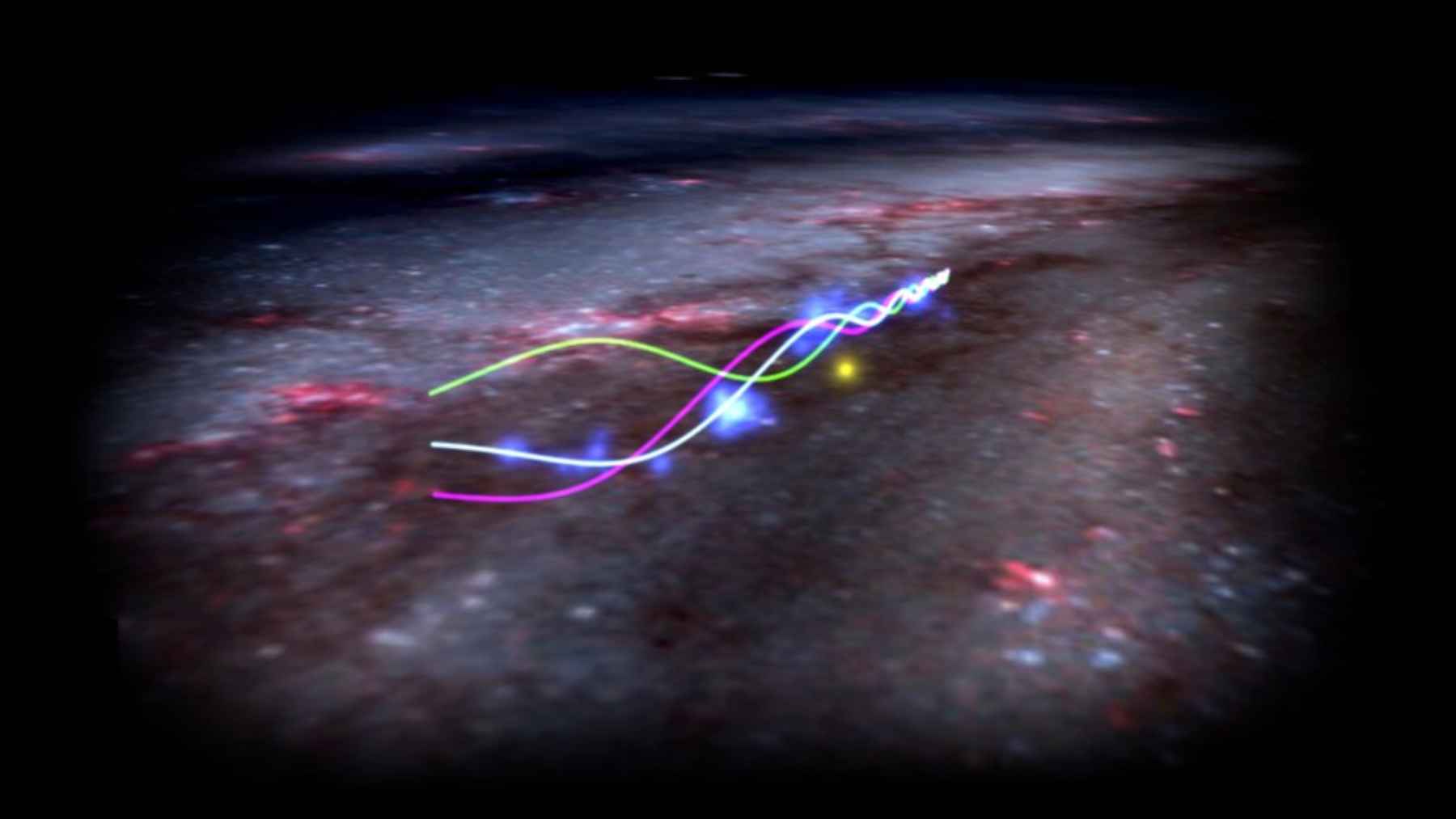

Star factories are nothing new. Nearby, regions such as the Orion Nebula show how giant clouds of gas and dust collapse into hot, bright young stars. In visible light they glow in colorful wisps. At longer wavelengths they shine because of tiny dust grains warmed by the intense radiation of newborn stars.

What makes Y1 stand out is the temperature of its dust. Using ALMA’s highly sensitive Band 9 receivers, which observe light at a wavelength of 0.44 millimeters, the team measured dust grains glowing at about 90 Kelvin, close to minus 180 degrees Celsius. That may sound cold compared with a kitchen oven, yet for a distant galaxy it is strikingly warm.

Coauthor Yoichi Tamura of Nagoya University notes that this is much hotter than dust in similar early galaxies, confirming that Y1 is, in his words, an “extreme star factory.” The warmth tells scientists that young, massive stars are flooding their surroundings with energy and that the interstellar medium is already rich enough in heavy elements to form dust.

Extreme star formation rate in galaxy Y1

From that temperature and brightness, the team estimates a star formation rate of more than 180 solar masses per year. Our own galaxy usually manages roughly one solar mass in the same amount of time. A pace like Y1’s cannot last for long on cosmic timescales, so astronomers think they are catching it during a brief, intense growth spurt that would quickly reshape the galaxy.

These short, hidden bursts may finally explain a long standing puzzle. Many very young galaxies appear oddly dusty, even though they have not had time to build dust in the slow way older stars usually provide it. Researcher Laura Sommovigo points out that “galaxies in the early universe seem to be too young for the amount of dust they contain,” yet Y1 shows that a small mass of hotter dust can shine as brightly as a large mass of cooler grains.

In practical terms, that means astronomers might have been overestimating how much dust some early galaxies hold. A little warm dust can light up a young system, tricking surveys into thinking there is more material than there really is. Y1 becomes a calibration point, a reminder that temperature matters as much as quantity when reading the universe’s infrared glow.

Early stars and the elements that shape Earth

Why should anyone who worries about oceans, forests or their electricity bill care about a blazing galaxy so far away? Because places like Y1 are where the universe first forged many of the elements that later ended up in planets, atmospheres and living cells. The carbon in tree trunks, the oxygen in the air and the silicon in solar panels all trace their story back to early generations of stars in violent systems like this one.

The study, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society under the title “A warm ultraluminous infrared galaxy just 600 million years after the big bang,” is one more step toward a full timeline of how galaxies grow and enrich their surroundings.

Astronomers now plan deeper and sharper ALMA observations to map Y1 in detail and to search for more objects of the same kind. Somewhere in the noisy radio data from the early cosmos, they suspect many other superheated star factories are waiting. Each one is another chapter in the long story that eventually leads to familiar things on Earth, from night sky stargazing to the fragile climate we are trying to understand and protect.

The study was published on the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society website.

Image credit: ALMA – Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array.