If you have ever heard an older loved one pause mid-thought and say, “What is the word I am looking for,” you have witnessed word finding difficulty (WFD) in real time. It is common, often harmless, and easy to dismiss as normal aging. But new research suggests the bigger signal is not the rare missing noun. It is the overall pace of speech.

Across lab tasks and everyday conversation, scientists are finding that a gradual slowdown in fluent speaking can track cognitive health more reliably than the occasional verbal snag. That insight could change how clinicians screen for early decline and how families interpret what they hear at the dinner table.

Word finding difficulty is common, but patterns matter

WFD happens to everyone, especially when stressed, tired, or distracted. Language is a high speed relay between memory, meaning, and the mouth, and even small delays can create that “tip of the tongue” feeling. With age, these moments can become more frequent.

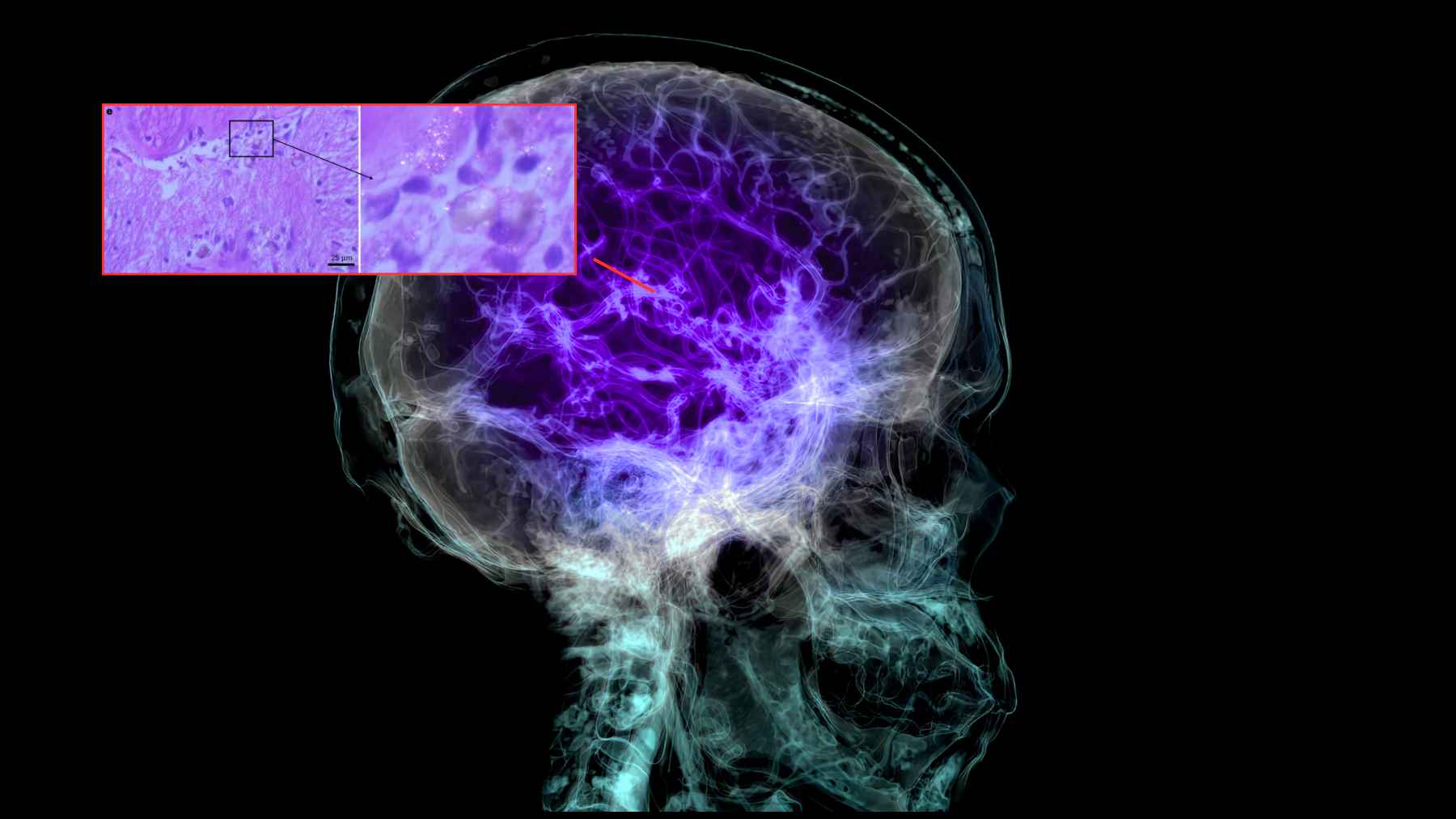

The challenge is separating normal aging from early warning signs. Researchers have linked WFD to brain pathways that are also affected in Alzheimer’s disease, including work associated with the University of Toronto and Baycrest Health Sciences. Still, the newest evidence argues that a single lapse is not the headline. The headline is tempo.

In other words, it may matter less that someone pauses to search for a word and more that their sentences, once underway, arrive more slowly than they used to.

Three theories explain why speech changes with age

Scientists tend to group explanations for age-related word retrieval changes into three ideas.

One is the processing speed theory. Think of the aging brain like a computer that still works but opens files more slowly. Words can be retrieved, but each step takes longer.

Another is the inhibition deficit hypothesis, which argues that older adults have a harder time suppressing irrelevant ideas. Competing words crowd in, and selection becomes harder.

A third explanation is the transmission deficit hypothesis. It describes vocabulary as a layered network where the link between meaning and sound gets weaker with age. A person knows the concept but struggles to activate the word’s sounds.

These theories sound abstract, so researchers test them with controlled experiments designed to tease apart meaning, sound, and speed.

A picture word game put language under the microscope

A popular tool is the picture word interference task. Participants see an image (like a dog) while a distractor word appears or plays. If the distractor is semantically related (like “cat”), naming often slows. If it is phonologically related (like “fog”), naming can speed up because the sound cue helps.

In a study of 125 adults ages 18 to 85, researchers turned this task into a fast paced online game and also collected executive function measures and samples of natural conversation for later analysis.

Older participants showed stronger slowing when a meaning related distractor appeared and gained less benefit from sound related cues. Those patterns fit the transmission deficit hypothesis, which predicts weaker connections between word forms and their sounds.

But when the team compared the lab signals with real world speech, a surprising detail stood out.

The strongest indicator was raw speed, not specific errors

Semantic interference and phonological facilitation in the lab did not neatly predict everyday word finding problems. What did predict them was overall reaction time, meaning the basic speed of retrieving and producing words.

Follow up analyses also pointed in the same direction. People who spoke more slowly tended to score lower on tasks involving planning and focus, even when obvious word finding errors were uncommon. Pauses spent hunting for a specific word were not the most consistent marker. The broader slowing of fluent speech was.

That distinction matters because it can ease unnecessary worry. A loved one forgetting a name once in a while may be experiencing normal aging. A steady, noticeable slowdown in speech rhythm may deserve closer attention.

What this could change in clinics and at home

Researchers are now arguing that speech rate should be treated like a practical cognitive vital sign. Today, many standard screens emphasize accuracy, such as naming items correctly. The study’s authors suggest that reaction time in picture naming may be more sensitive than accuracy for early detection, especially since common tools like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment often focus heavily on whether the word is correct rather than how long it took to retrieve it.

Technology could accelerate this shift. Speech analysis software can measure tiny timing changes in pauses and pacing, which could one day help flag subtle decline earlier than traditional memory tests.

For families, the takeaway is simple and humane. Do not pounce on every “what’s that word” moment. Instead, watch for broader patterns over time. If speech becomes steadily slower, or if language changes come with confusion, safety issues, or difficulty managing daily tasks, it is worth discussing with a clinician.

In the meantime, daily habits that keep language active still make sense. Storytelling, conversation, word games, and learning new vocabulary all exercise the networks that support speech. And when someone pauses, patience helps. Often the right word arrives when the pressure lifts.

The full study appeared in the journal Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition.