You expect plastic in a water bottle or a grocery bag. You probably do not expect it in your brain. Yet a landmark analysis of donated human organs has confirmed that tiny plastic fragments are lodged deep inside the frontal cortex, and in amounts that surprised even the scientists who dissolved the tissue to measure them. Are those particles quietly reshaping our health, or simply along for the ride?

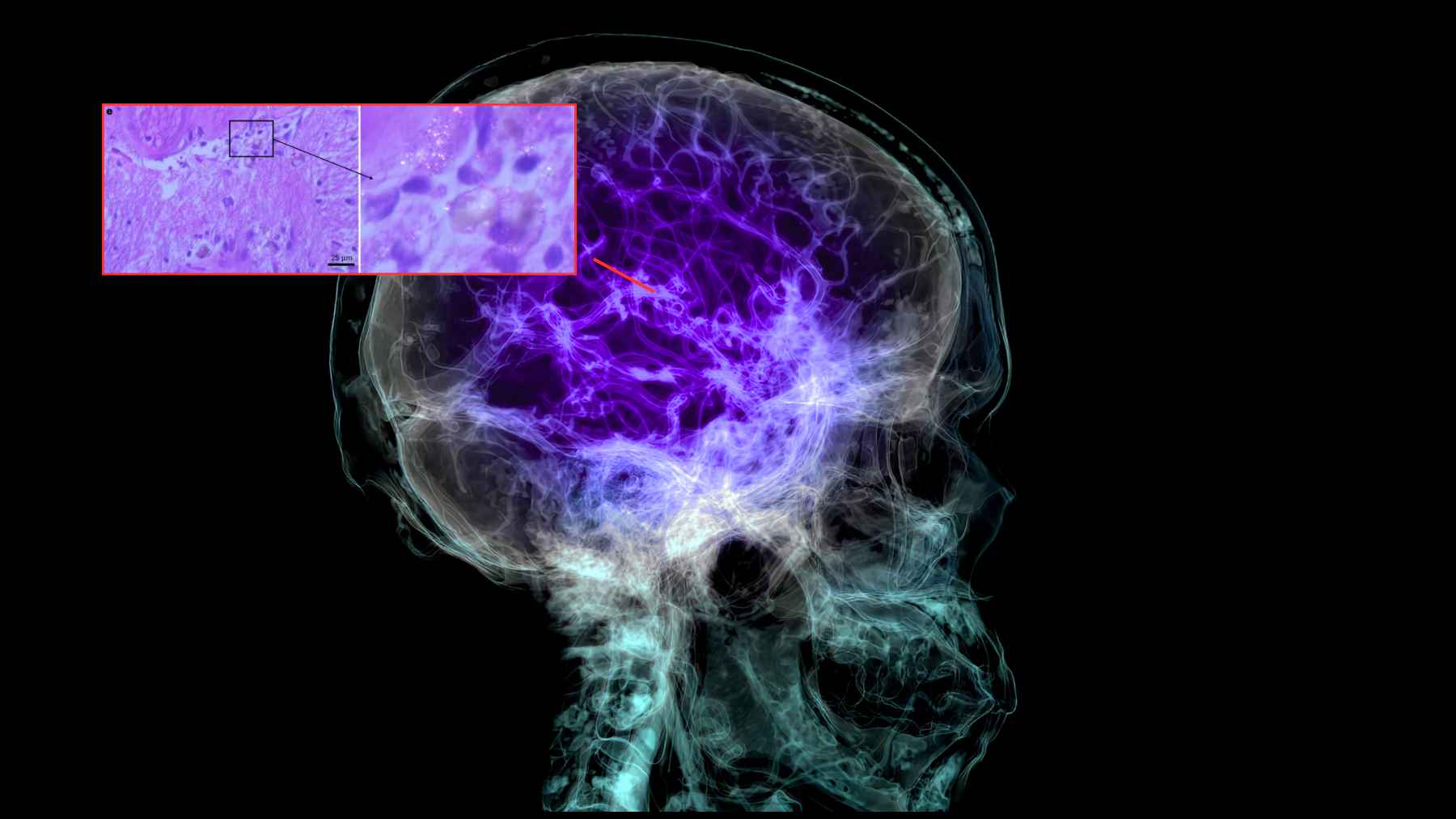

In the new study, researchers at the University of New Mexico used a harsh alkaline solution to “digest” samples of liver, kidney and brain taken at autopsy. What remained was a residue of solid particles that were examined with advanced chemical techniques. Every tissue contained microplastics and nanoplastics. The brain samples stood out.

On average they held between seven and thirty times more plastic than the liver or kidney, with median concentrations rising from 3,300 micrograms per gram of brain tissue in 2016 to nearly 5,000 micrograms per gram in 2024.

Most of those particles were shards of polyethylene, the same basic polymer used in grocery bags and many food packages. Under the electron microscope they look like jagged splinters less than two hundred nanometers long, far smaller than a human hair. Brains from people who had lived with dementia contained several times more plastic than those from people without a diagnosed cognitive condition, and fragments showed up in blood vessel walls and in clusters of immune cells.

To help people picture the scale, lead toxicologist Matthew Campen has estimated that an adult brain could contain roughly five to ten grams of plastic, about the weight of a small crayon or a plastic spoon. He and his colleagues stress that this figure is an extrapolation, not a precise measure for every person, yet it hints at how deeply plastic pollution has invaded our bodies.

What current studies say about microplastics and disease

Before you imagine your neurons wrapped in plastic wrap, there is an important caveat. The scientists are careful to say that their data show where plastics are, not what they are doing. At the end of the paper they note that the findings are associative and do not prove that plastic fragments cause dementia or any other brain disease.

Other experts have also urged caution, pointing out that methods need further validation and that contamination is a constant risk when measuring plastics in fatty tissues like the brain.

Even so, the brain study does not stand alone. In 2024 a large investigation in the New England Journal of Medicine examined carotid artery plaques removed during surgery and found microplastics in the clogged vessels of nearly 60% of patients.

Those patients were several times more likely to suffer a heart attack, stroke or early death over the next three years than patients whose plaques contained no detectable plastic, even after accounting for traditional risk factors such as age, cholesterol and smoking.

Animal studies are adding more pieces to the puzzle. A Science Advances experiment in 2025 showed that when mice were given microplastics in their bloodstream, immune cells swallowed the particles and then became stuck inside the tiny capillaries that feed the brain. These blockages acted much like microscopic clots. Blood flow slowed, and the animals developed short-term problems with movement and behavior.

Stepping back, a comprehensive review commissioned for California policymakers concluded that microplastics are “suspected” to harm human reproductive, digestive and respiratory health, based on a mix of human and animal data.

The authors underlined that the evidence is still limited and often methodologically weak, yet patterns of inflammation, oxidative stress and tissue damage keep turning up in different organs.

Plastic pollution in everyday life and the environment

None of this should be shocking when you look at the bigger picture. The world produced around 460 million metric tons of plastic in 2019, and output is expected to roughly triple by 2060 if policies do not change. As larger items crumble, they shed billions of particles that ride the wind and water.

Microplastics have been detected in fresh Antarctic snow, deep ocean trenches, household dust, tap and bottled water and a long list of foods from table salt to seafood. One frequently cited estimate suggests the average person now ingests the equivalent of a credit card in plastic every week.

For many people this is not an abstract threat. Surveys from Germany show that “microplastics in food” have become the top environmental health concern for consumers, even though most respondents feel poorly informed about the science. Health agencies such as the World Health Organization currently judge the overall risk from microplastics to be uncertain but probably low for most people, while still recommending efforts to cut exposure and curb plastic pollution upstream.

How to reduce your exposure to microplastics

So what can you realistically do while scientists argue over decimals and detection limits? Everyday choices matter to a certain extent. Using fewer single-use plastics, choosing reusable bottles and containers, avoiding heating food in plastic and venting kitchens to reduce indoor dust are all practical steps that can lower your personal intake, especially when combined with a diet that leans more on fresh foods and less on highly-packaged, ultra-processed products.

Why policy on plastic pollution matters

At the end of the day, the heaviest lift will not come from swapping coffee cups at home. It will come from policies that slow plastic production, redesign packaging and tighten regulations on chemical additives. Negotiations for a global plastics treaty have stumbled over whether to cap virgin plastic output, yet the emerging picture of plastics in human brains, arteries and lungs keeps raising the stakes.

For now, the message from researchers is sober. Microplastics and nanoplastics are turning up in some of our most protected organs, the brain included, in amounts that are rising over time. The true health impact remains uncertain, but the trend is moving in only one direction.

The study was published in Nature Medicine.