Hundreds of millions of years before dinosaurs walked on land, Earth’s oceans went through a crisis so severe that nearly half of all marine genera vanished. New geochemical research now points to a prime suspect in that ancient disaster, and it was not just a simple lack of oxygen. It was hydrogen sulfide, a poisonous gas that can turn entire stretches of sea into a death zone.

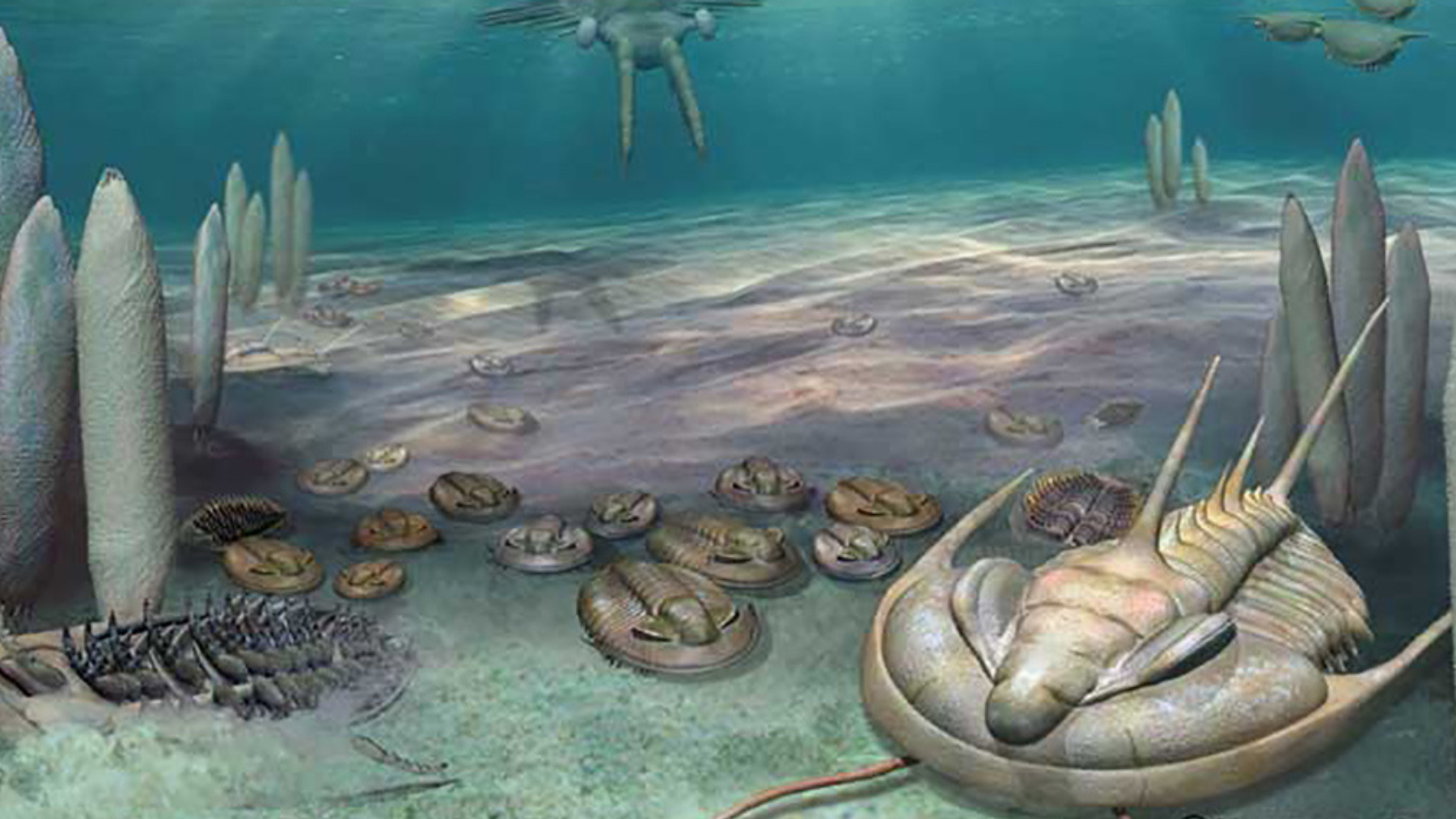

This mass extinction struck during Cambrian Age 4, around 509 to 514 million years ago, shortly after the famous Cambrian explosion brought a burst of new marine life. Fossil records show that roughly 45 percent of marine genera disappeared in that interval, making it the first major extinction of the Phanerozoic.

For years, many scientists believed the kill mechanism was widespread anoxia, meaning oceans that simply ran short on oxygen. The idea was that booming Cambrian ecosystems filled the seafloor with organic debris, which microbes then consumed, stripping oxygen from the water column and suffocating animals.

Hydrogen sulfide, euxinia and lethal marine conditions

The new study, led by geochemist Chao Chang and colleagues and published in Geophysical Research Letters, paints a darker picture. By analyzing molybdenum isotopes and other chemical markers in black shales from a drill core on the Yangtze Platform in South China, the team found evidence that large parts of the ocean did not just become oxygen poor. They became euxinic, filled with hydrogen sulfide.

Hydrogen sulfide is the same gas that gives rotten eggs their smell. In high enough concentrations it is deadly to most complex life. The plain language summary of the paper states that “sulfidic waters enriched in H2S are lethal for marine animals,” and the authors argue that a transitory expansion of such waters around continental margins likely drove the extinction.

Molybdenum isotopes and global ocean redox

To reach that conclusion, the researchers turned to molybdenum, a trace metal that flows from land to sea and behaves in a predictable way under different redox conditions. In normal, well-oxygenated oceans, its isotopic signature stays relatively stable on a global scale.

Under strongly sulfidic conditions, however, molybdenum can be stripped from seawater and locked into sediments. Chang explains that molybdenum “can combine with sulfur to form insoluble compounds” that sink and accumulate on the seafloor.

In the Yangtze Platform core, molybdenum isotope values during the two main extinction pulses climb to what the authors describe as modern levels. That pattern is hard to explain with a small local dead zone. Instead, it points to a global ocean where sulfidic waters along continental margins expanded, boosted molybdenum burial, and briefly pushed the whole marine system into a more toxic state.

Between these extinction intervals the picture looks different. Iron speciation, uranium and molybdenum data suggest that shallow and mid depth waters were, for the most part, oxygenated, while deeper zones saw shifting pockets of anoxia and sulfide. This supports the idea of a generally improving oxygen environment through the early Cambrian, one that helped complex animals diversify, interrupted only when hydrogen sulfide surged.

So how did the seas tip into toxicity? The authors propose a chain reaction. An earlier burst of biological productivity likely pumped large amounts of organic matter into the water column. Microbes then burned through this material and, once oxygen became scarce, turned to sulfate, producing hydrogen sulfide as a byproduct. The result was a wave of sulfidic water that spread across continental margins and into sunlit layers where many animals lived.

Modern ocean deoxygenation and coastal dead zones

If that sounds uncomfortably familiar, you are not alone. Modern scientists are documenting a quieter, human-driven version of the same basic process in today’s oceans. Since the 1960s, the global ocean has lost about 2 percent of its oxygen, and low oxygen zones in the open ocean have expanded by roughly 4.5 million square kilometers. More than 400 coastal “dead zones” have been identified worldwide, many linked to nutrient pollution from farms and cities that fuels algal blooms and, later, oxygen-hungry decay.

In many of these hypoxic and anoxic settings, microbes in seafloor sediments already produce hydrogen sulfide. Studies show that this sulfide can leak into overlying waters, especially in highly productive coastal regions, and it is known to be toxic to most aerobic organisms. We are nowhere near Cambrian scale euxinia, but the underlying chemistry is surprisingly similar.

Lessons from ancient marine extinction for today’s oceans

At the end of the day, the Cambrian story is a reminder that ocean oxygen is not guaranteed. When biology, climate and chemistry line up in the wrong way, seas that once nurtured life can flip into a hostile state. The new work by Chang and colleagues suggests that such flips can be brief in geological terms, yet devastating for the creatures that live through them.

For policymakers and coastal communities worried about fish kills, foul smelling shorelines and shrinking catches, that ancient signal in the rocks carries a simple message. Once oxygen is gone and sulfide takes over, recovery is slow, and many species do not get a second chance.

The study, “Mass extinction coincided with the expansion of continental margin euoxinia during the Cambrian 4” (Chang et al., 2023), was published in Geophysical Research Letters (DOI: 10.1029/2023GL105560).

Image credit: Marianne Collins, Royal Ontario Museum.