Just after three in the morning on December 12, a telescope in Northern Ireland caught a sudden flash on the Moon’s darkened face. In less time than a blink, a bright dot appeared and vanished, the kind of thing you would miss completely if you glanced at your phone at the wrong second.

Astronomers now think that flash was a tiny space rock smashing straight into the lunar surface at extreme speed. The recording is believed to be the first video of a lunar impact flash made from Ireland and only the second ever captured anywhere in the United Kingdom, turning an ordinary cold December night into a small milestone for space science.

A blink-and-you-miss-it explosion on the lunar night side

The event was spotted at 03:09:36 UTC by the Armagh Robotic Telescope at the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, using an automated camera trained on the Moon’s night side. The observation is credited to Andrew Marshall-Lee, a final year doctoral student who was monitoring the live feed when the frame lit up with a sharp white flash.

Because the impact happened on the unlit part of the Moon, there was no glare from sunlight to hide it. On the raw video, the flash lasts only a fraction of a second before the surface returns to its usual gray.

Catching something this brief is not easy. The Moon is huge in the sky, the flashes are tiny, and they are gone faster than a car headlight flicking past your window. That is why this single clip is being treated as a rare prize rather than just another night at the observatory.

Linked to the Geminid meteor shower

The timing of the impact lines up almost perfectly with the Geminid meteor shower, which runs each year from roughly December 4 to 20 and peaked the weekend after the flash. On Earth, the Geminids show up as bright “shooting stars” as grains of rock burn up in the atmosphere, a familiar sight for anyone who has stayed up late under a winter blanket to watch them.

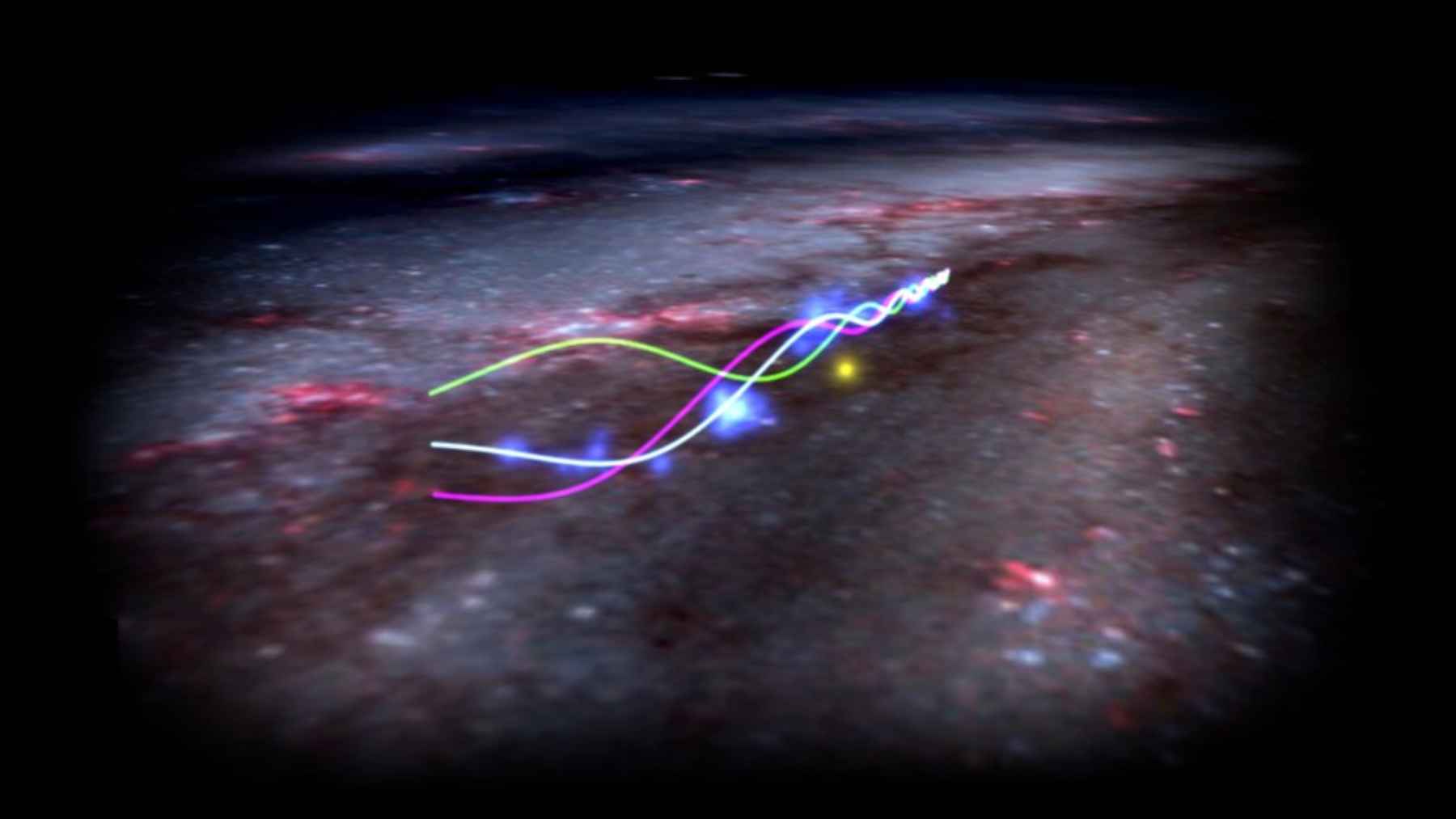

These meteors come from debris shed by the asteroid 3200 Phaethon, a rocky body that behaves in some ways like a comet as it swings close to the Sun and leaves a trail of dust behind. Armagh scientists say the speed of the impact, estimated at around 35 kilometers per second, matches what is usually seen from Geminid particles, making this the leading explanation even though the exact origin is still under study.

Early analysis suggests the impact site may lie about two degrees northeast of the bright Langrenus crater on the Moon’s eastern near side, an area many backyard telescope users already know well. If that location is confirmed, lunar orbiters may later be able to find the fresh scar and compare it with the video flash.

How a pebble-size rock can light up the Moon

The object that hit the Moon was probably no larger than a golf ball and far too faint to see before it struck. Yet slamming into bare rock at tens of kilometers per second releases as much energy as a large bomb, and almost all of that energy turns into heat and light in an instant.

According to the observatory’s initial report, the rock was likely completely vaporized on impact and carved out a new crater roughly ten meters wide, about the length of a small parking lot. That is a big change in the landscape caused by something you could hold in your hand.

On Earth, the same kind of rock usually burns up harmlessly as a meteor, leaving only a brief streak overhead and maybe a bit of panic in the group chat. The Moon has no air at all, so there is no gentle slowdown, no long glowing trail, only a brutal hit and an almost ghostly flash that careful observers on our planet can pick up with fast cameras.

Why lunar impact flashes matter for future missions

Tracking these flashes is about more than collecting dramatic videos. By counting how often different sizes of rocks hit the Moon, scientists can better estimate the number of small space objects near Earth, a key part of planning safe lunar bases, landers, and even satellites that might orbit low over the surface. Programs run by agencies such as NASA, which has shared earlier images ofl unar impact flashes, have already shown how powerful these tiny collisions can be.

Europe is also investing heavily in this work through efforts like the NELIOTA project, which uses dedicated telescopes to watch the Moon for flashes and is now being expanded into a new long term monitoring campaign. That broader network means the Armagh event can be compared with many others and folded into a growing database of impacts.

Earlier research using NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter linked a bright 2013 flash to a fresh crater about 35 meters wide, showing how video and later satellite images can be combined to tell the full story of a single impact. Scientists hope the new Irish recording will eventually get a similar follow up, turning one sharp burst of light into detailed knowledge about the rock that caused it and the crater it left behind.

For most people, the Armagh flash is just a tiny speck in a grainy clip, something you might scroll past between weather updates and the latest news. For researchers, it is another data point in the slow, careful effort to understand how often the Moon is hit and how that affects both lunar exploration and our own planet’s safety.

The official press release has been published in the online newsroom of Armagh Observatory and Planetarium.

Photography by Brennan Dincher.