When America’s energy race starts to focus on more than just making sure that all the homes have lights, you know that the race to save America is getting more serious. One of the core components of this race is looking at sustainable power methods to minimize and eventually fully eliminate reliance on fossil fuels. One magic number is the sure goal, 65 gigawatts.

America seeking to be energy independent

It seems as if monthly electricity demands are at its highest during summer months, however, the U.S. has always took to using coal, nuclear, or even natural gas to match the growing demand for electricity. Although so far, America has been able to supply enough electricity to meet the energy demand, global energy conflicts seem to be always on the rise.

In the world of energy automony, many countries, including America, are looking at alternative methods to generate and store electricity in more climate friendly ways. One such method is to rely on utility-scale battery storage that will enable countries, like America, to capture renewable energy when in abundance, especially at times when solar energy is at its peak or even during the right weather conditions.

Storage is of utmost importance to save America

While the idea is to save America, the word, “save,” may be quite an exaggeration. The idea is to ensure that America is energy independent and can stand on its own feet when it comes to power supply. The focus has moved towards larger battery storage that will be essential to ensure America’s economic security as well as the country’s environmental stability.

If America does not look towards independent energy infrastructure, the country could face issues such as:

- Fuel price volatitity leading to drastic economic disturbances.

- More blackouts throughout the country when energy demand increases.

- Over reliance on foreign energy supplies,.

- Industries struggling without constant power supply.

With commercial energy being in demand with the increase in data center expansion, it has become more necessary for America to consider its place in the energy race. An unprepared grid will be far from being able to handle the rise in electricity needs due to the increase in the popularity of AI, cloud computing, and even electric vehicles.

Relying on utility-scale battery storage is perhaps the best way to ensure that we cut down on relying on fossil fuels and maximize the benefit that we can reap from peak energy supply moments. America’s pathway to the net zero emissions agenda is clear.

Increase of renewable power

With solar generation systems increasing in popularity, the solar generation is expected to grow by 33% this summer as has been stated by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

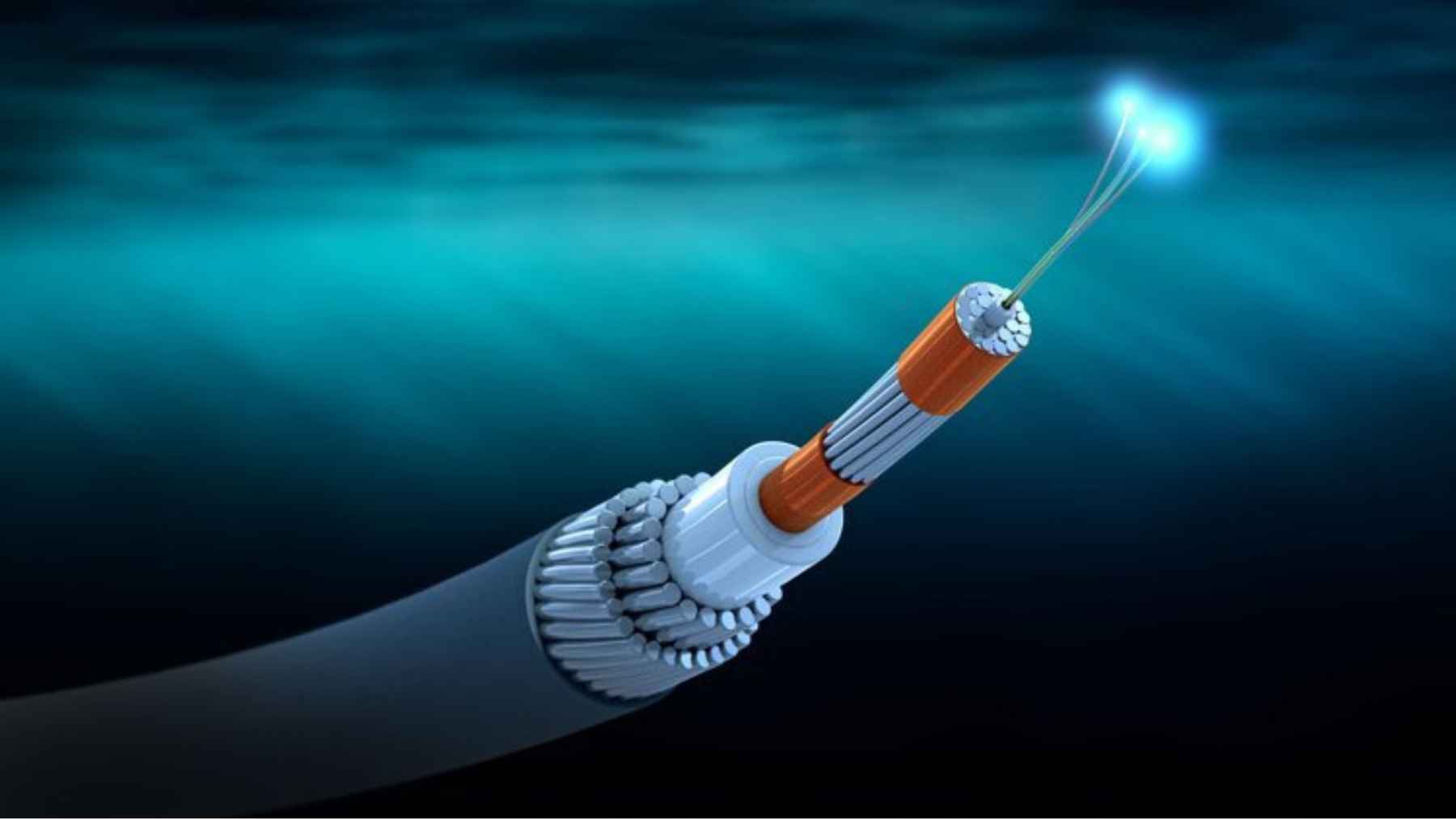

Hydroelectric power is also said to increase by about 6% due to better water supplies in the West. Such a shift to renewable power sources (such as solar systems) means energy generation methods that makes the most of clean energy. America surely is ready for one of its largest solar project ever with 10,000 rooftops vanishing under the coastlines.

65 GW needed for America’s survival

The magic number 65 GW means that while America may be looking at utility-scale battery storage to scale up on clean energy, 65 GW is the total utility-scale battery storage capacity that the U.S. has to reach by 2026 as per the EIA. Initially, the figure was only 17 GW back in early 2024 and now the figure is up to 65 GW.

This 65 GW capacity will ensure that:

- America’s grid gets stabilized even at times of excessive energy demands.

- The reliance on foreign oil and gas is reduced and that America remains independently energy seucre.

- Various industries like transportation remains supported with the reliable backup power.

The energy race has just about started and with a figure of 65 GW in mind, the U.S. is looking at ways to become more energy-independent. Soon, clean energy can be produced and stored effectively. America may be turning off photovoltaic energy, but America is redefining its power grid.

Disclaimer: Our coverage of events affecting companies is purely informative and descriptive. Under no circumstances does it seek to promote an opinion or create a trend, nor can it be taken as investment advice or a recommendation of any kind.