For once, there is climate news that feels like a breath of fresh air. Scientists report that the 2025 Antarctic ozone hole was the smallest and shortest‑lived in five years and it closed earlier than usual, a sign that the damaged shield high above our heads is slowly healing.

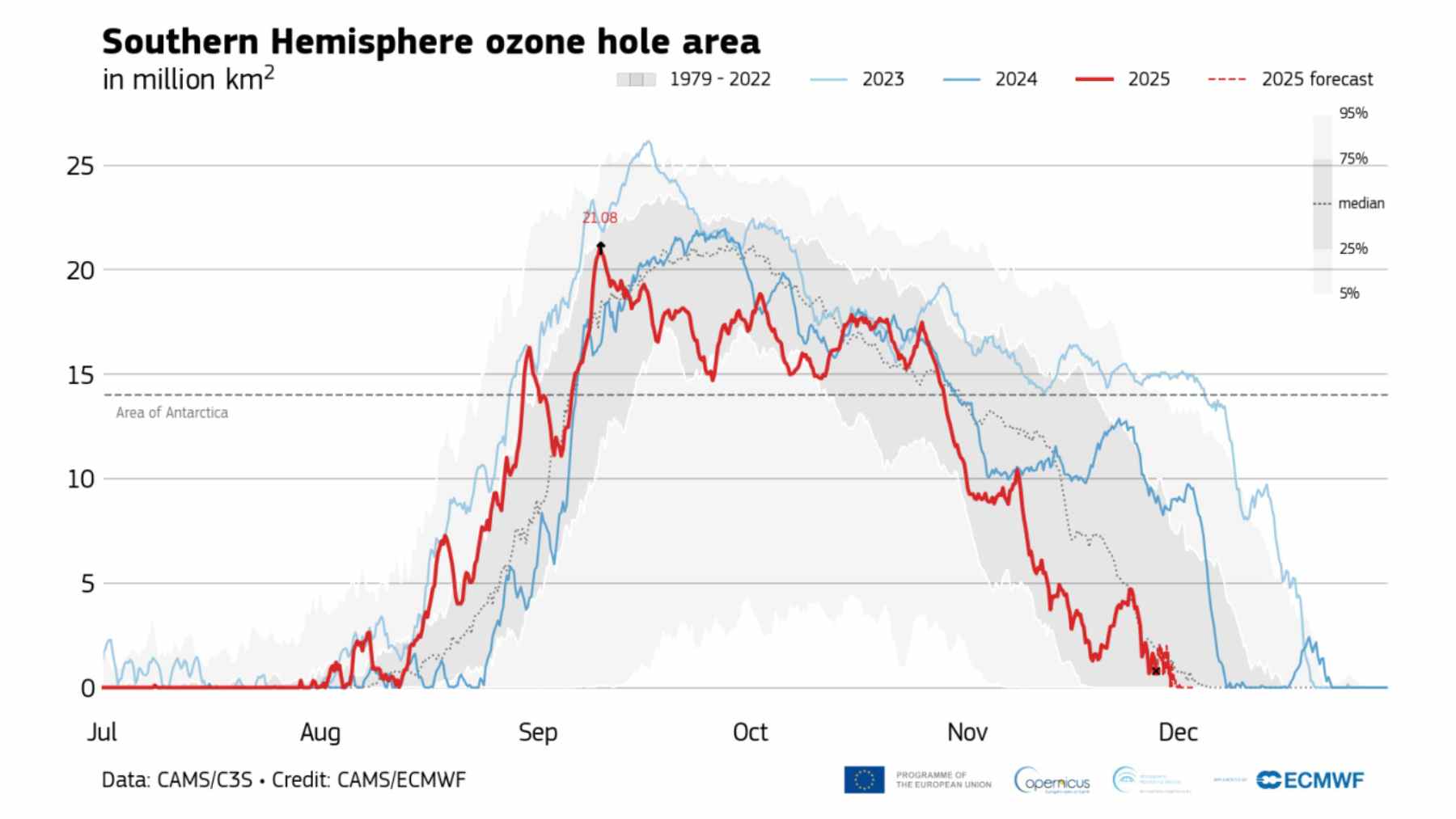

Data from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service show that the hole closed on December 1, the earliest closure since 2019, after reaching a maximum area of about 21 million square kilometers in early September, clearly below the 26.1 million measured in 2023. For the second year in a row, the average size and duration were smaller than the very large, long-lasting holes seen between 2020 and 2023, and ozone concentrations inside the hole were higher than in those previous years.

On top of that, a joint assessment from NOAA and NASA ranks the 2025 hole as the fifth smallest since 1992, the year when the Montreal Protocol really started to bite into emissions of ozone‑depleting chemicals.

So what exactly is closing up above Antarctica, and why does it matter to someone putting on sunscreen before a summer walk?

The ozone layer and our daily lives

The ozone layer sits between roughly 15 and 35 kilometers above Earth and absorbs most of the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. Without this thin shield, skin cancer rates would soar, crops and marine plankton would be damaged and even outdoor time in the middle of the day could become risky in many regions.

The so‑called ozone hole is not a literal gap. It is a seasonal thinning of ozone high in the stratosphere that appears every Southern Hemisphere spring when very cold temperatures and polar winds combine with man‑made chemicals. Over Antarctica that thinning can grow until it covers an area larger than the entire African continent before slowly shrinking again as the stratosphere warms.

Anyone who has checked the UV index before a beach trip has felt the practical side of this story. When the ozone layer weakens, that index climbs.

What made 2025 different

In 2025, the Antarctic ozone hole developed relatively early in mid August and then expanded, peaking near 21.08 million square kilometers in early September. After that, it hovered between about 15 and 20 million square kilometers through late October before shrinking quickly during November. The hole finally closed on December 1, one of the earliest endings in the satellite record.

Compared with the huge and persistent holes from 2020 to 2023, which often stretched beyond 25 million square kilometers and lingered well into December, this season looked more modest. Copernicus scientists also noted that ozone inside the hole was generally higher than in those recent extreme years, which supports the idea that the layer is slowly rebuilding.

It is not a straight line, though. Atmospheric experts point out that factors such as stratospheric temperatures, wind patterns and even volcanic eruptions can nudge the hole larger or smaller from one year to the next. The huge eruption of the Hunga Tonga volcano in 2022, for example, injected large amounts of water vapor into the stratosphere that may have helped drive unusually large holes afterward.

Montreal Protocol and a rare environmental success

To a large extent, the hopeful tone around the 2025 season reflects decades of work under the Montreal Protocol. This global treaty has phased out most chlorofluorocarbons and other ozone‑depleting substances that once leaked from refrigerators, foams and spray cans into the upper atmosphere.

By the United Nations and World Meteorological Organization assessments, those chemicals have already peaked in the stratosphere and are slowly declining. Models suggest that if countries keep honoring the treaty and its later amendments, Antarctic ozone should return to near 1980 levels around the middle of this century, likely in the 2060s.

In practical terms, that means fewer extreme ozone hole years, a gentler UV index over time and better protection for human health and ecosystems, even as the planet keeps grappling with record heat at the surface.

Why scientists still urge caution

The small 2025 hole is good news, but researchers are careful not to declare victory too early. Year-to-year variability remains high. Wildfires and large volcanic eruptions can temporarily worsen ozone loss, and climate change is altering temperatures and circulation patterns in the stratosphere in ways that are still being studied.

Experts also warn about emerging pressures, including illegal emissions of banned chemicals and the rapid growth of the space launch industry, which could inject reactive substances into the upper atmosphere and complicate recovery if not managed carefully.

At the end of the day, the 2025 ozone story is a reminder that global environmental agreements can work when they are enforced and updated, but they still need constant follow up. The small hole over Antarctica may feel far away from the city street or farm field, yet it quietly shapes the sunlight that reaches all of us.

The official statement was published on Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.