Off the coast of Vancouver Island, deep under the waves and far below the seafloor, Earth’s outer shell is literally ripping apart.

A new study in Science Advances shows that the oceanic plate diving beneath the Pacific Northwest is breaking into pieces, marking the slow “death” of part of the Cascadia subduction zone. Scientists have long suspected that subduction zones eventually shut down, but this is the first time they have been able to watch the process unfolding in such detail. (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

For coastal communities that already live with tsunami evacuation maps on the fridge, any talk of tearing plates naturally raises a question. Does this make the big Cascadia quake more or less likely?

The short answer is that the overall hazard remains roughly the same on human time scales. Cascadia is still capable of producing very large earthquakes and tsunamis. The new work mostly refines our picture of how and where those quakes might rupture. (sciencedaily.com)

How to stop a runaway plate

Subduction zones are where one tectonic plate sinks beneath another. They recycle old seafloor, feed chains of volcanoes, and power some of the largest earthquakes on the planet.

Once a dense slab starts to sink, its weight pulls the rest of the plate along. That “slab pull” is so strong that ending subduction usually requires what the authors call a tectonic accident.

Lead author Brandon Shuck uses a more down-to-earth image. “Getting a subduction zone started is like trying to push a train uphill, it takes a huge effort,” he explains.

Once that train is racing downhill, stopping it takes something dramatic on the track. In northern Cascadia, that something is a tangled boundary called the Nootka Fault Zone.

The plate that cracked into a microplate

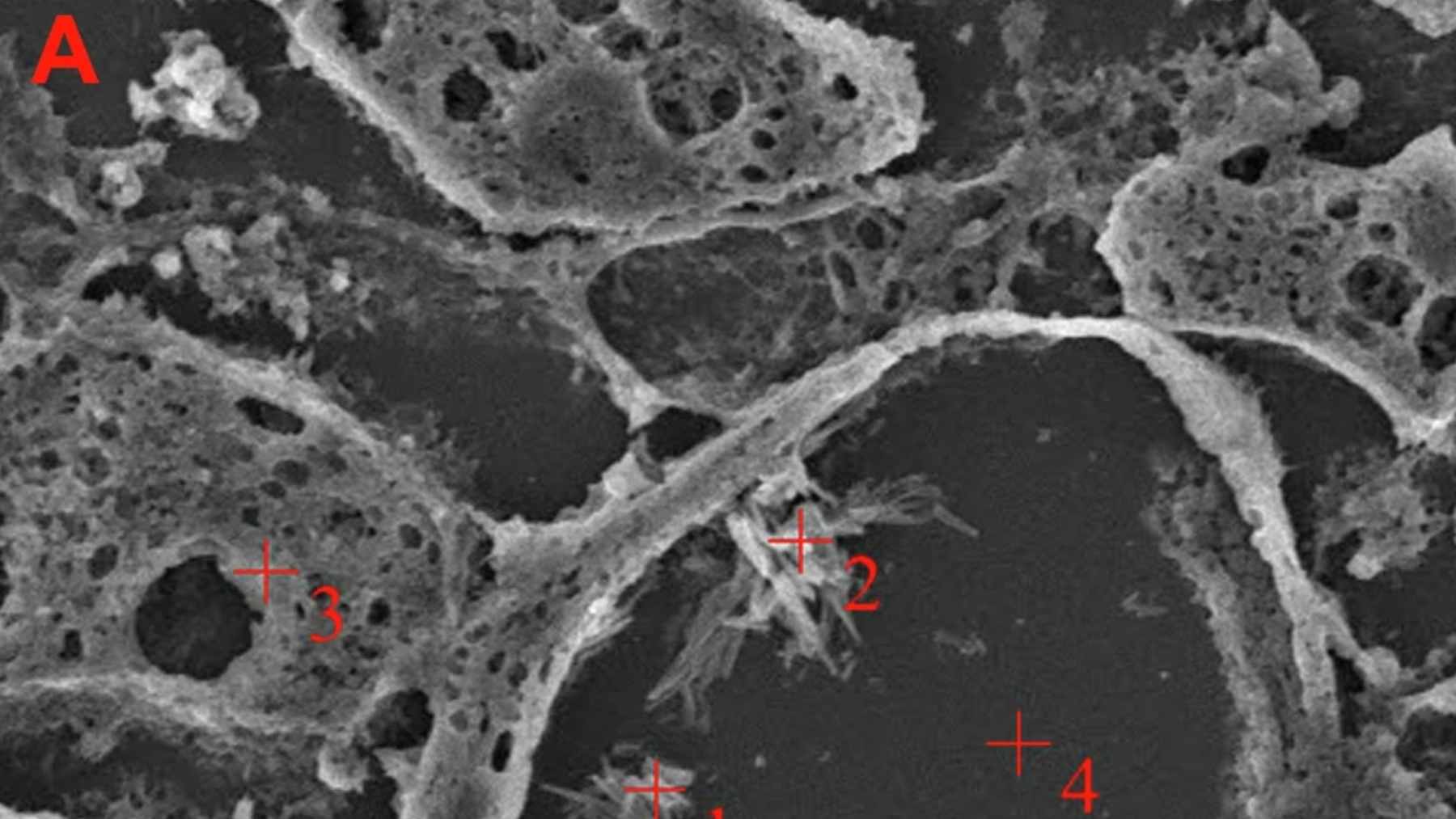

Using ultra-deep seismic reflection data from the 2021 CASIE21 survey plus tens of thousands of earthquake records, the team imaged the crust offshore Vancouver Island almost like a medical ultrasound of the planet.

They found that what used to be a single oceanic plate has been sliced into two parts. On one side lies the better known Juan de Fuca plate. On the other sits a smaller block called the Explorer microplate. A narrow shear zone about twenty kilometers wide separates them where the Nootka Fault Zone cuts from the seafloor down into the upper mantle.

GPS data already hinted that something odd was going on. Explorer dives beneath North America at roughly two centimeters per year, while neighboring Juan de Fuca subducts at more than four centimeters per year. In other words, one conveyor belt is slowing while the other keeps running.

Beneath the seafloor, the images reveal steep fractures where the underthrust slab suddenly steps downward by several kilometers. Chains of earthquakes line up along these fractures, forming near-vertical walls of seismicity that reach to about forty kilometers depth. The researchers interpret them as tears ripping through the sinking plate.

One tear under the Explorer microplate looks especially mature. The slab there has dropped sharply, and parts of the break have gone strangely quiet, which hints that chunks may already have detached. Neighboring Juan de Fuca shows a gentler bend rather than a sharp break, suggesting that its slab tear is still in an earlier stage.

What this means for earthquakes and volcanoes

So what does a dying subduction zone mean for life on land?

In the near term, scientists do not see a reason to rewrite Cascadia’s hazard maps. The region can still host a magnitude 9 class megathrust earthquake that would shake the Pacific Northwest and send a tsunami racing toward the shore. The new tears could influence how such a rupture starts or stops, but they do not switch the danger off.

Over millions of years, the story becomes more dramatic. As each slab fragment finally snaps off, it leaves a gap called a slab window. Hot mantle can then rise through that opening, feeding patches of unusual volcanism and possibly lifting the overlying crust.

The study estimates that once the Explorer slab fully lets go, the Cascadia subduction zone will effectively shorten by about seventy five kilometers, roughly one-twelfth of its current length.

Some volcanoes in interior British Columbia already show geochemical signs that may fit with mantle flow around a torn slab, although researchers caution that more work is needed to pin down that link.

A reminder of Earth’s restless engine

From an everyday perspective, all of this is glacially slow. The plates creep at the speed our fingernails grow. Yet on the scale of Earth history, what scientists have captured off Vancouver Island is a rare snapshot of a basic planetary process. Subduction zones do not simply appear and vanish. They fray, fragment, and pass the tectonic baton to new plate boundaries.

For people living along the Pacific coast, the message is twofold. The big Cascadia quake remains a serious risk worth planning for with sturdy buildings, coastal escape routes, and emergency kits. At the same time, this new work shows that the same tectonic forces that threaten our cities also drive the long-term renewal of the planet’s surface.

The study was published in Science Advances.