Two decades ago, scientists at NASA looked at the small, icy moon Enceladus and made a bold claim. They argued that this frozen speck orbiting Saturn hid a global ocean and the chemistry needed for life, instead of being a dead iceball.

For years, that idea rested on indirect clues from plumes, gravity data, and hints of hydrothermal activity deep below the ice. Now a new study of old Cassini data, published in late 2025, has finally confirmed that the moon’s ocean is rich in complex organic chemistry and key elements for life. So what changed after all this time, and why are scientists so excited about grains of ice that nobody can see with the naked eye?

Cassini’s daring bet on an ocean world

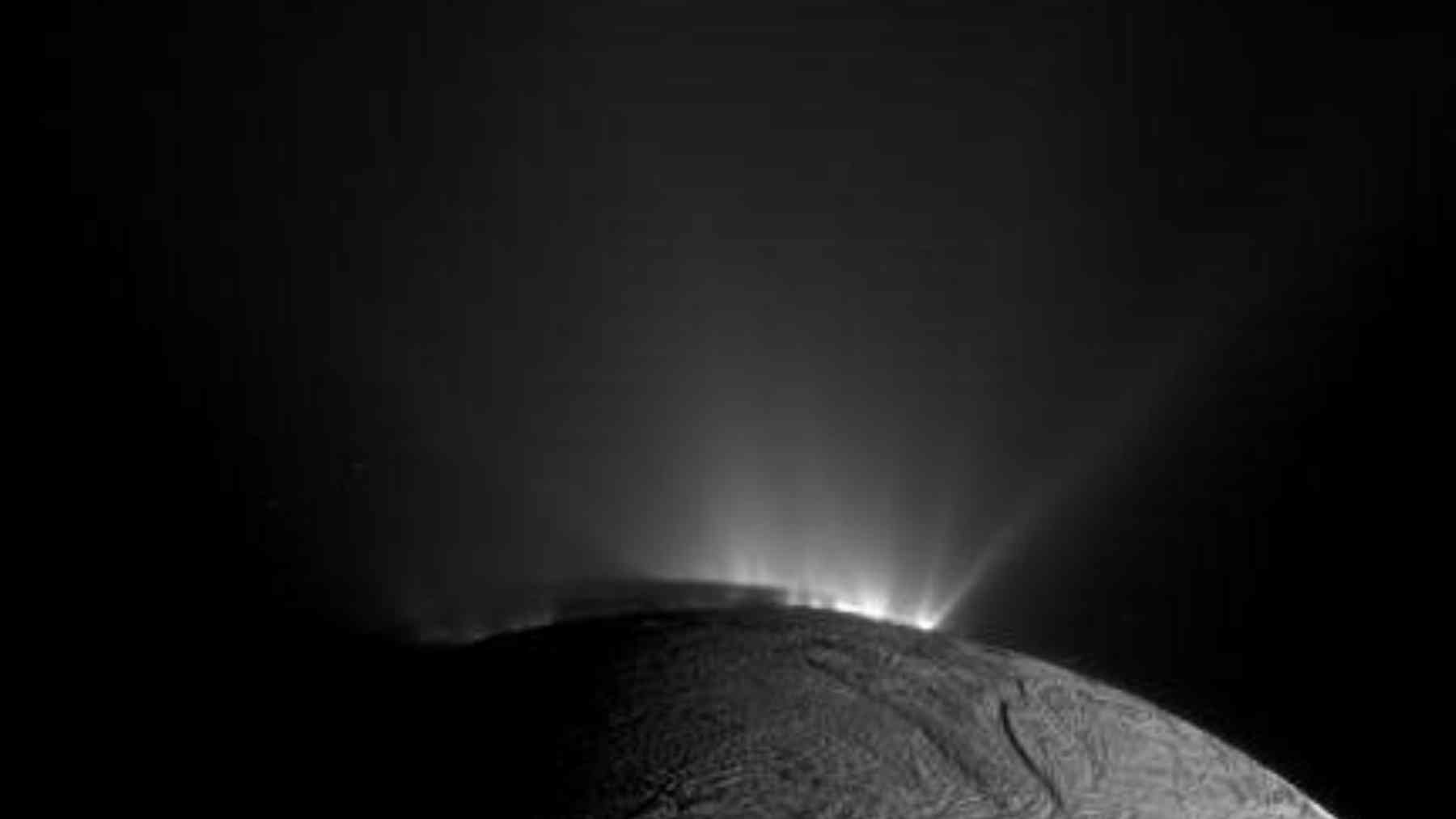

The Cassini–Huygens mission slipped into orbit around Saturn in 2004 and soon turned its attention to Enceladus. Early flybys revealed jets of water vapor and ice shooting from fractures near the south pole, the famous tiger stripes, pointing to a liquid ocean under the crust.

Those first results transformed Enceladus into a flagship “ocean world” in the outer solar system. Over time, Cassini data showed that the hidden sea is global and likely warmed from below by hydrothermal vents where hot water meets rock, a setup that on Earth can support thriving ecosystems far from sunlight.

The new breakthrough did not come from a fresh spacecraft visit. Instead, it came from scientists at Freie Universität Berlin who went back to one of Cassini’s closest and fastest flybys of Enceladus in 2008. Using improved analysis tools, the team led by planetary scientist Nozair Khawaja pulled new chemical fingerprints out of mass spectrometer data that had been sitting in archives for years.

Fresh ice grains from the south polar plumes

During that flyby, Cassini skimmed only about 13 miles above the south polar region and plowed straight through a dense part of the plume. At that height, the spacecraft’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer instrument smashed into individual ice grains at roughly 18 kilometers per second, fast enough to vaporize and electrically charge them.

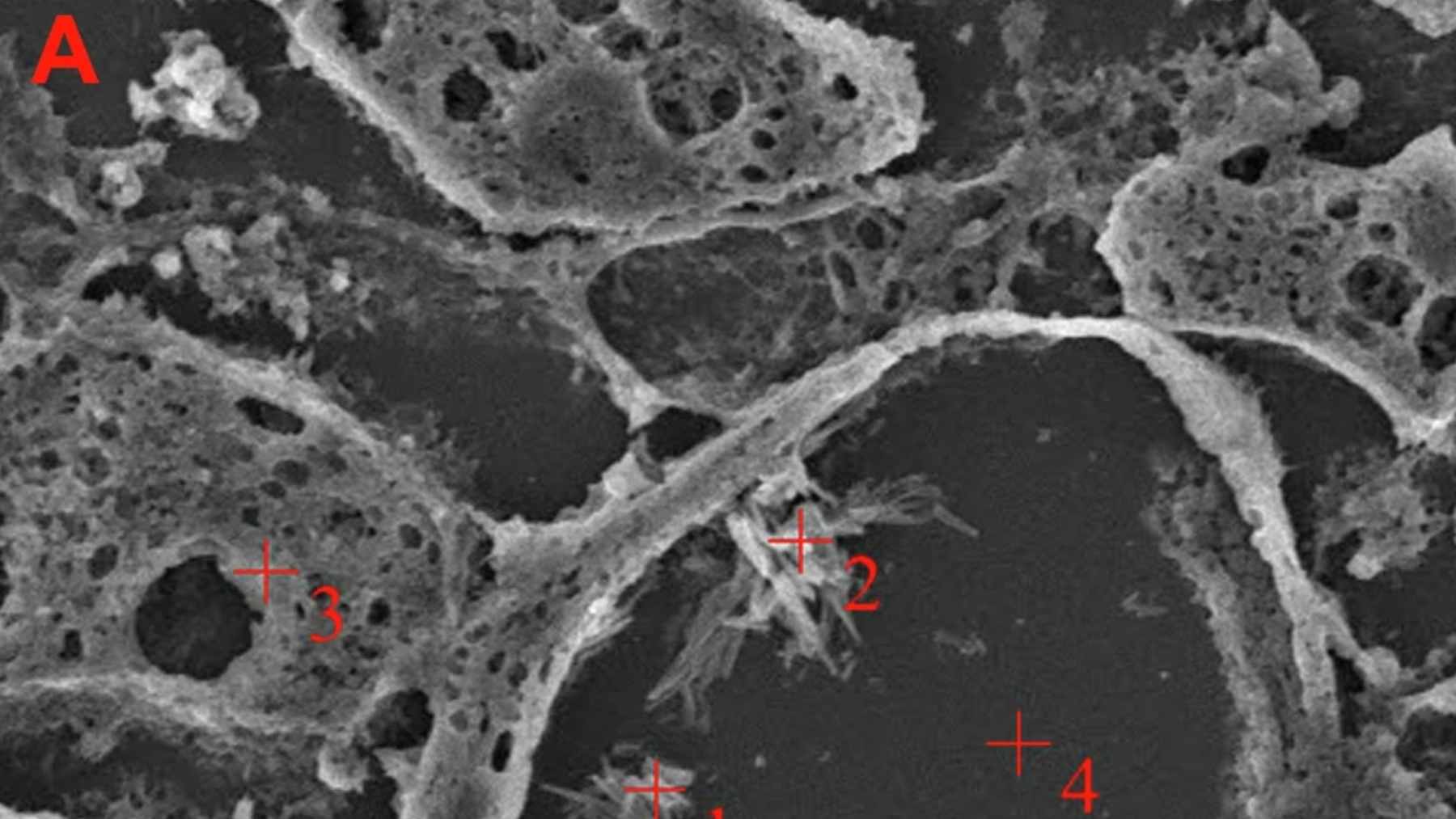

Those violent impacts might sound destructive, but they are exactly what a mass spectrometer needs. When the grains were torn apart, the instrument could sort the fragments by mass and charge, revealing which atoms and molecular groups were hiding inside each speck of ice.

There is another important twist. Earlier work mainly studied ice that had drifted into Saturn’s faint E ring, material that had been floating in space for months or years and exposed to harsh radiation. The new study focused on grains that had left the ocean only minutes before hitting Cassini, essentially giving researchers a direct sample of the subsurface water. As Khawaja put it, “These new organic compounds were just minutes old, found in ice that was fresh from the ocean below Enceladus’ surface.”

A chemical checklist for life

Inside those fresh grains, the team found a richer mix of organic chemistry than ever seen before at Enceladus. The fingerprints point to molecules from the ester and ether families, both in simple chains and ring-shaped structures, along with compounds that include nitrogen and oxygen.

These types of molecules are important because, on Earth, esters and ethers often show up in fats and other biological materials. Nitrogen and oxygen containing groups can act as stepping stones toward amino acids and other complex organics. The new work backs up earlier hints from Cassini and from lab simulations that Enceladus’s ocean hosts active chemistry rather than a static, frozen soup.

The story does not stop with organics. Over the past few years, separate studies using Cassini data have nailed down the presence of phosphorus in the form of phosphates in Enceladus’s ice, filling in the last missing piece in the classic CHNOPS set of life’s key elements. CHNOPS stands for carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur, and Enceladus now appears to have all six in its ocean and plumes.

Geochemical models published in 2025 suggest that sulfur and iron are also available in dissolved form at the seafloor, at levels that could support microbial metabolisms if life ever arose there. Together with liquid water and energy from hydrothermal vents, researchers say the chemistry looks, to a large extent, fully habitable.

Why this tiny moon now sits at the front of the life hunt

All of this does not mean Enceladus is teeming with microbes. Scientists are careful on that point. The new molecules and elements show that the ingredients and energy sources are present, but they do not yet reveal whether biology has actually started using them.

Still, for the most part, the evidence lines up in Enceladus’s favor. Tiny ice grains have gone from vague hints to detailed chemical messages, carrying news from a dark ocean hundreds of miles down. Compared with more distant targets, it is almost as if nature is spraying samples into space for us to collect.

That is why agencies are already sketching the next steps. The European Space Agency is studying a mission concept that would send an orbiter and lander to the south polar region in the early 2040s, while other teams explore ideas for sample return missions that could bring plume material back to Earth.

For anyone who has stared up at the night sky and wondered if we are alone, Enceladus has quietly moved to the top of the list of places to watch. At the end of the day, the message from this small moon is simple and powerful. The chemistry for life is not unique to Earth.

The main study has been published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.