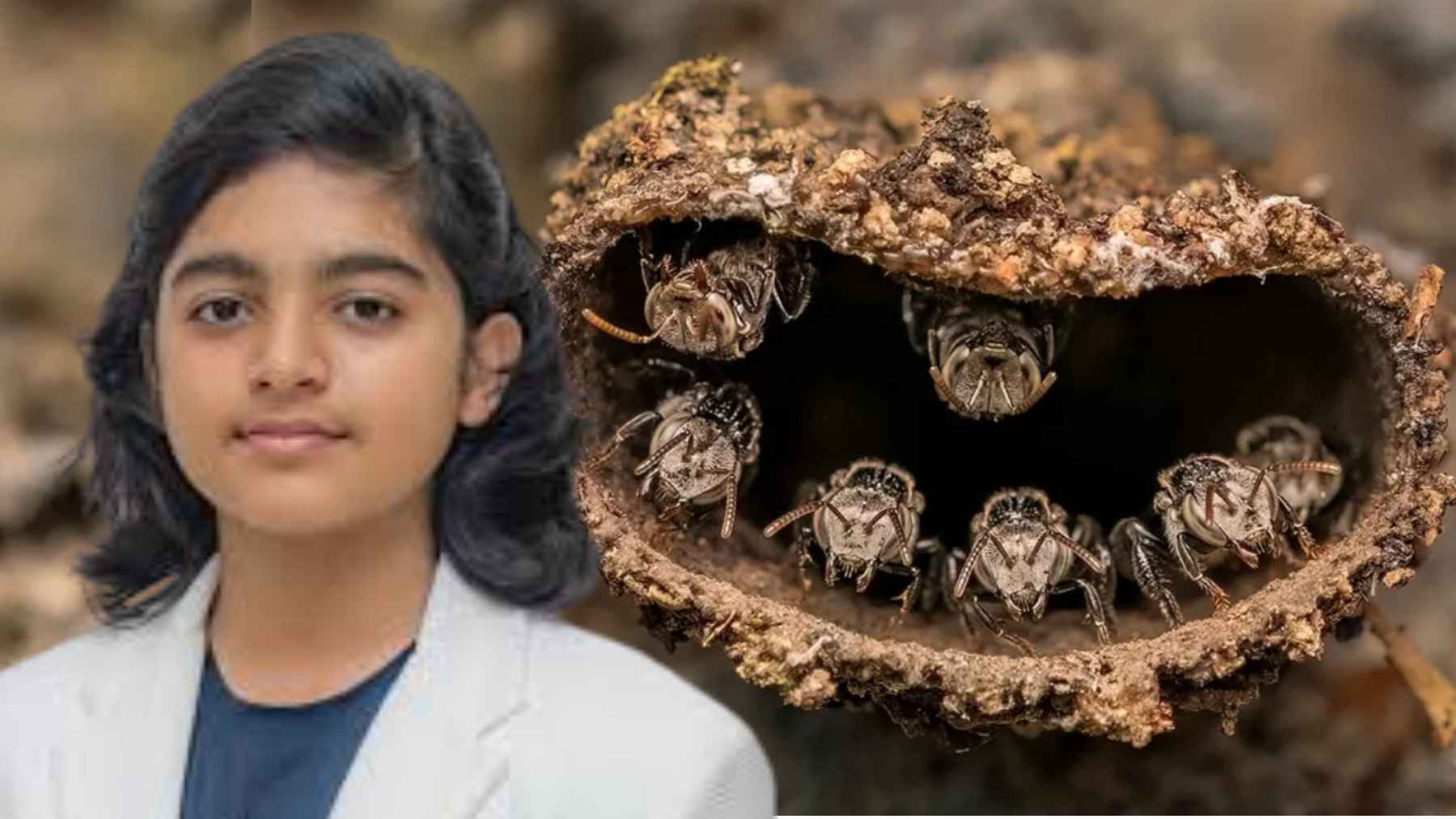

He is only 14 years old, used a 10-year-old camera, and won the world’s most important macro photography contest with a photo of bees in India

Young wildlife photographer Rithved Girish has been named Young Close‑up Photographer of the Year 7 for his image “Guardians of the Hive,” winning the…..

Driver’s licenses for people over 70 in California are expiring, and they must now appear in person every five years or they will be breaking the law

Most older Californians rely on their car for everyday life, from grocery runs to doctors’ visits. In a country where about 91% of adults…..

The combination of baking soda and hydrogen peroxide that is so popular in 2026 seems like a magical and inexpensive solution, but experts warn that it depends greatly on where it is used and when it is discontinued

Goodbye to BMW, Mercedes, and Volkswagen: an economist warns that these brands could disappear before 2030

If you write using a mixture of upper and lower case letters within the same word, this is what your brain could be revealing, according to psychologists

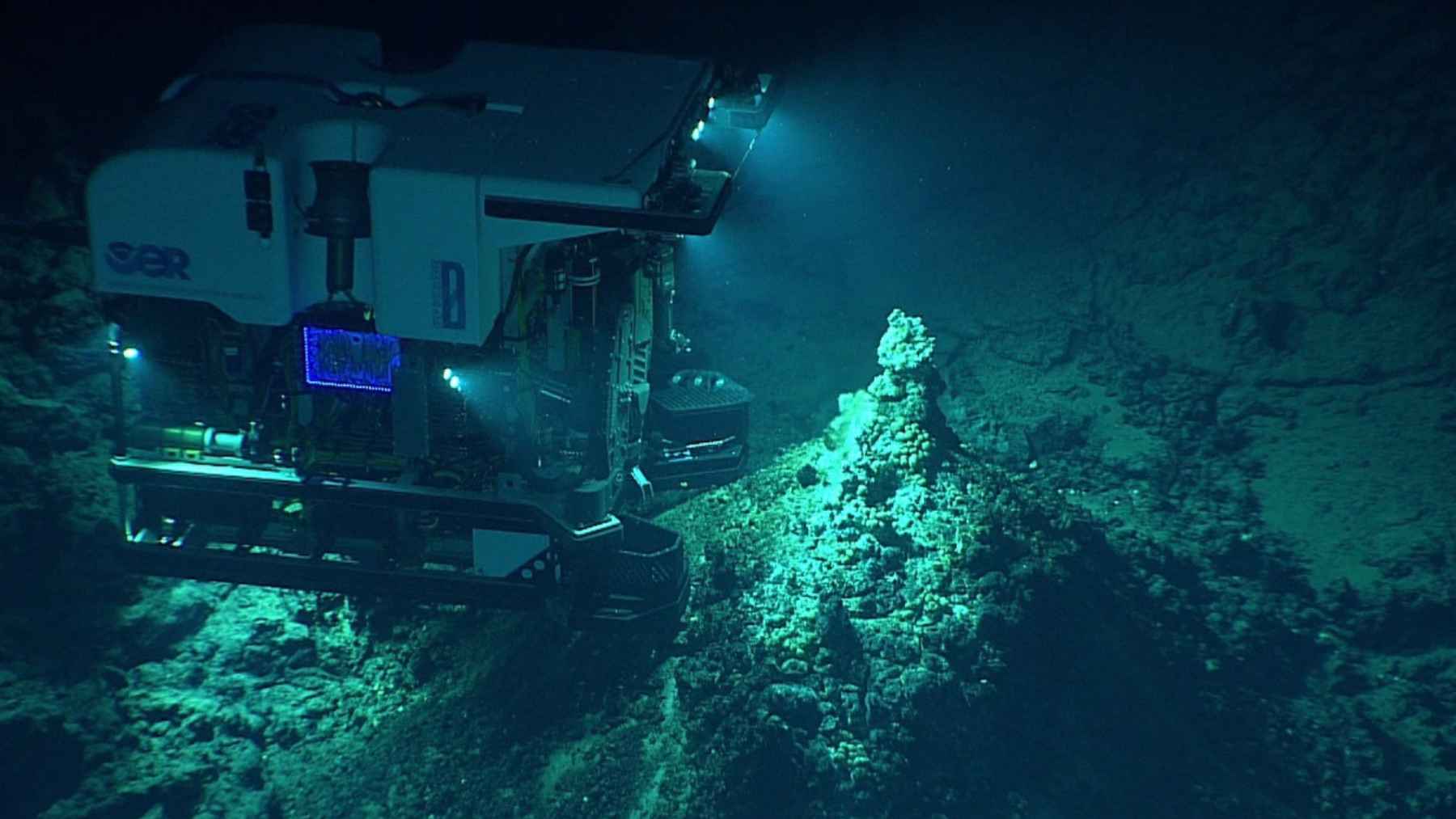

A deep-sea mission detects mud containing valuable elements where no one was looking. The discovery, made at a depth of 6 kilometers, could change the course of technology

Millions of people could lose their food this month following the implementation of a controversial law requiring 80 hours of work to retain SNAP benefits

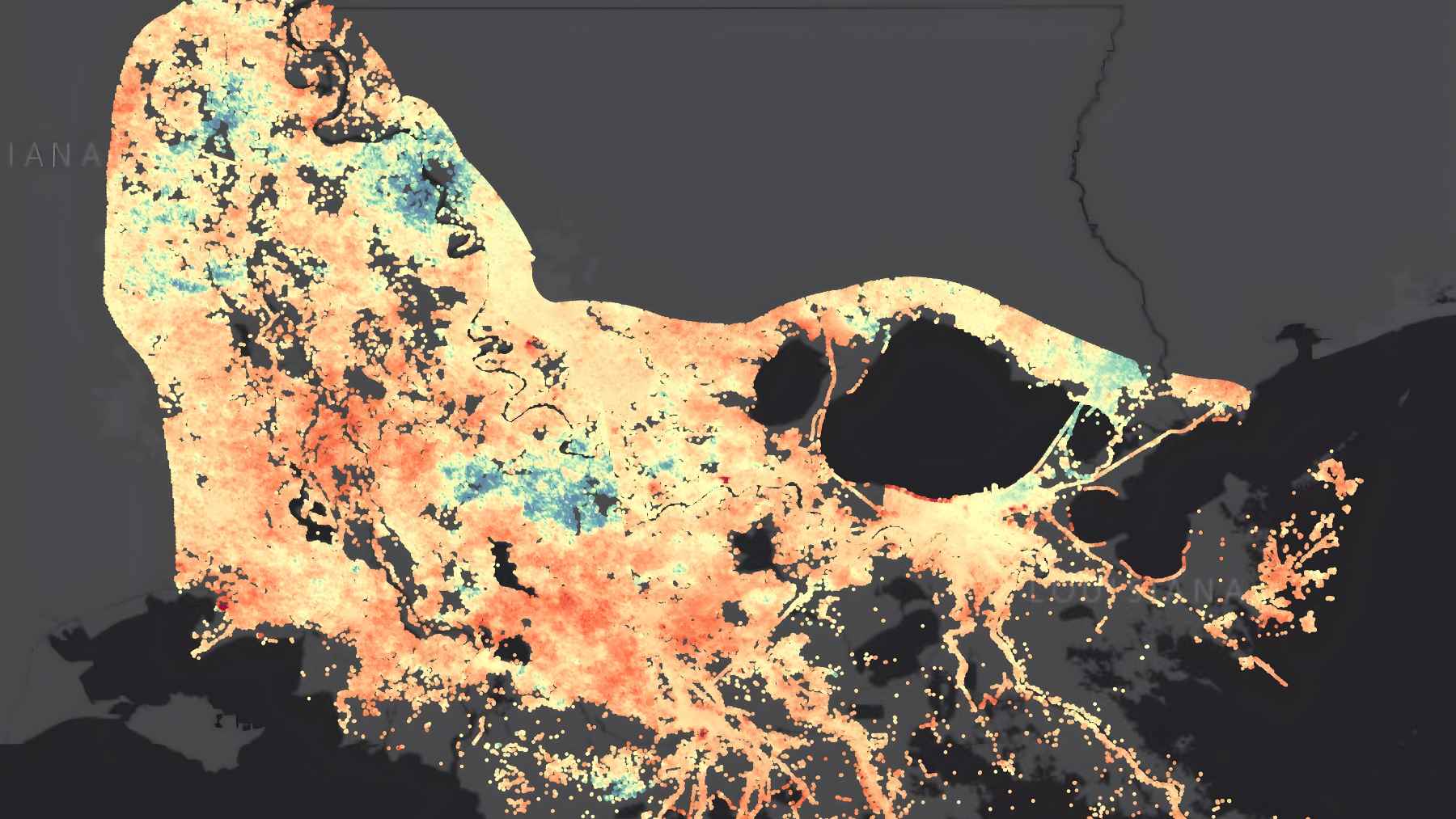

The greatest danger to megacities is not climate change, but something happening beneath our feet

Your brain could be full of microplastics… and you don’t even know it

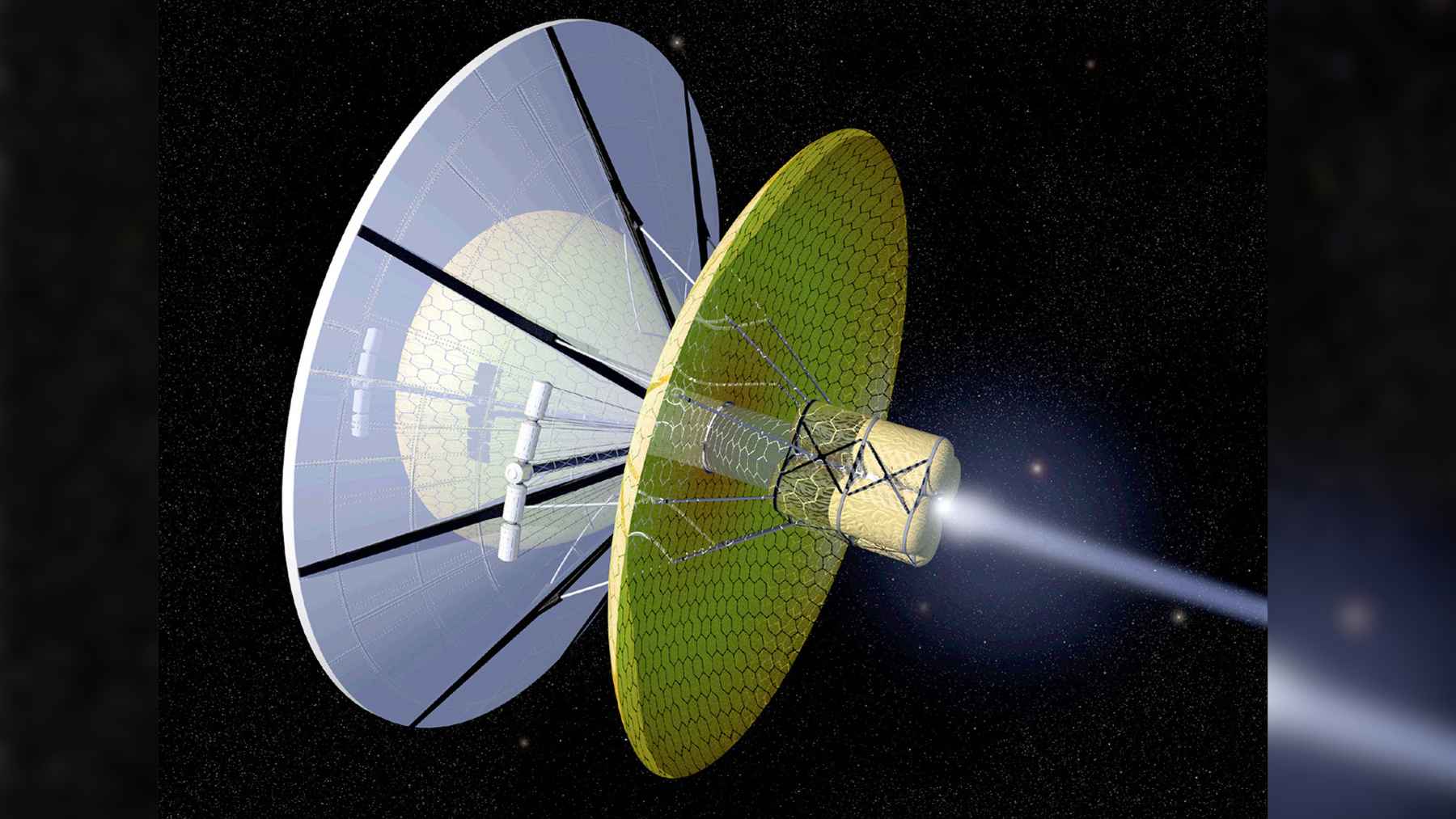

NASA conducts the first test of its nuclear engine for interstellar travel

Science

The combination of baking soda and hydrogen peroxide that is so popular in 2026 seems like a magical and inexpensive solution, but experts warn that it depends greatly on where it is used and when it is discontinued

A simple mix of baking soda and hydrogen peroxide is turning up on cleaning blogs,…..

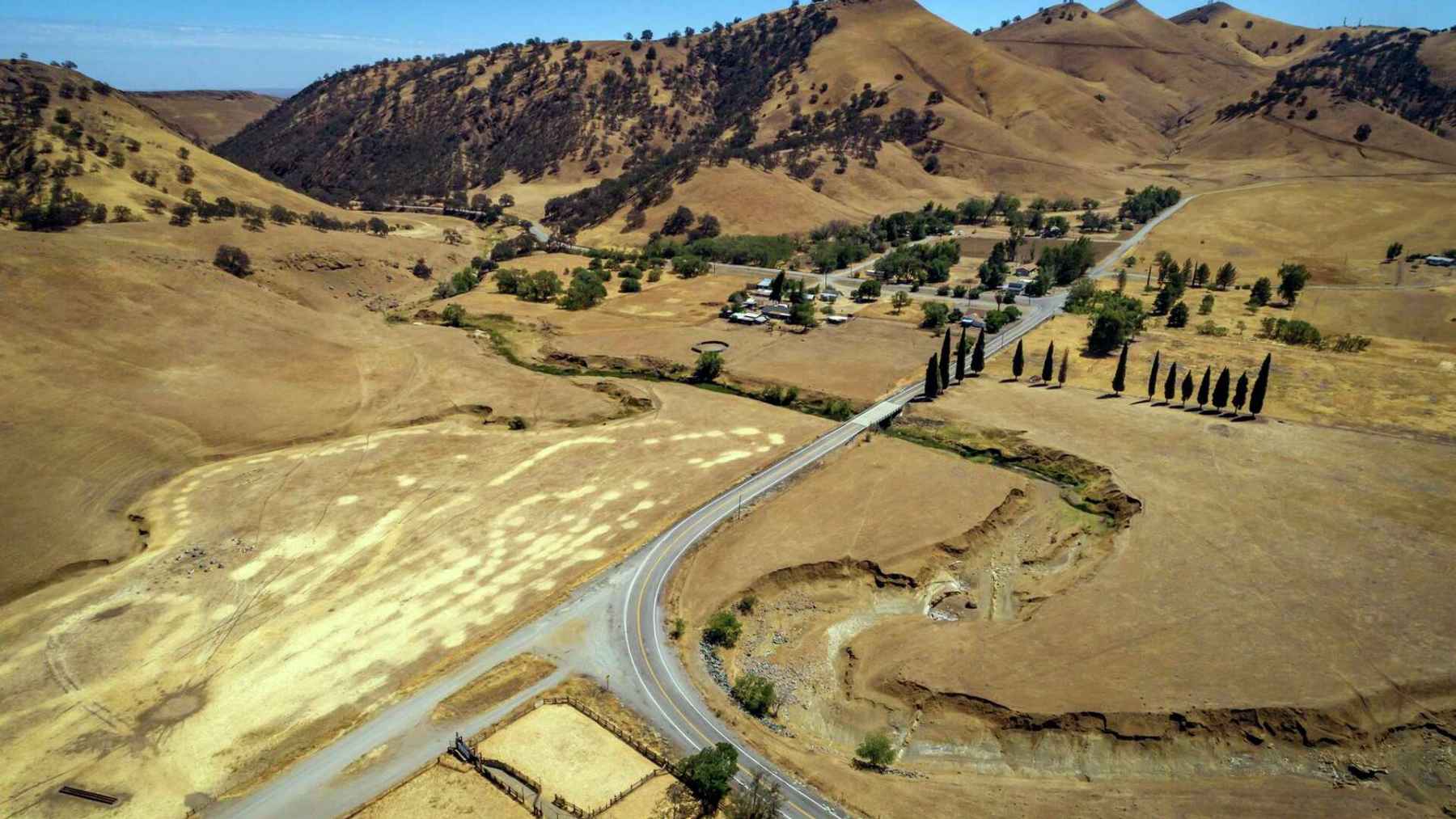

Science confirms that heat waves are literally accelerating the aging process

Many of us treat heat waves as a short-term annoyance. We close the blinds, crank…..

A deep-sea mission detects mud containing valuable elements where no one was looking. The discovery, made at a depth of 6 kilometers, could change the course of technology

Far from any traffic jam or smokestack, the research ship Chikyu from Japan is quietly…..

Goodbye to bulldogs and poodles: experts explain why more than 400 dog breeds would disappear almost completely in less than a decade if humans ceased to exist

Humans and dogs have lived side by side for thousands of years, but the explosion…..

The greatest danger to megacities is not climate change, but something happening beneath our feet

Across the planet’s great river deltas, the ground is dropping faster than the ocean is…..

Your brain could be full of microplastics… and you don’t even know it

Most of us now accept that plastic has reached nearly every corner of the planet……

A simple dinner could expose you to the same carcinogenic chemical as tobacco smoke

For a few weeks, people were yanking black plastic spatulas out of drawers and tossing…..

Scientists analyze 763 dogs in nine regions of Ukraine and discover that the front is “producing” wolf-like dogs in a matter of months, claiming that this is natural selection, not genetic magic

War in Ukraine has filled screens with images of ruined cities and displaced families. What…..

The Great Pyramid of Giza could be thousands of years older than we thought, according to a controversial study

Did the ancient Egyptians really build the Great Pyramid when your school textbook says they…..

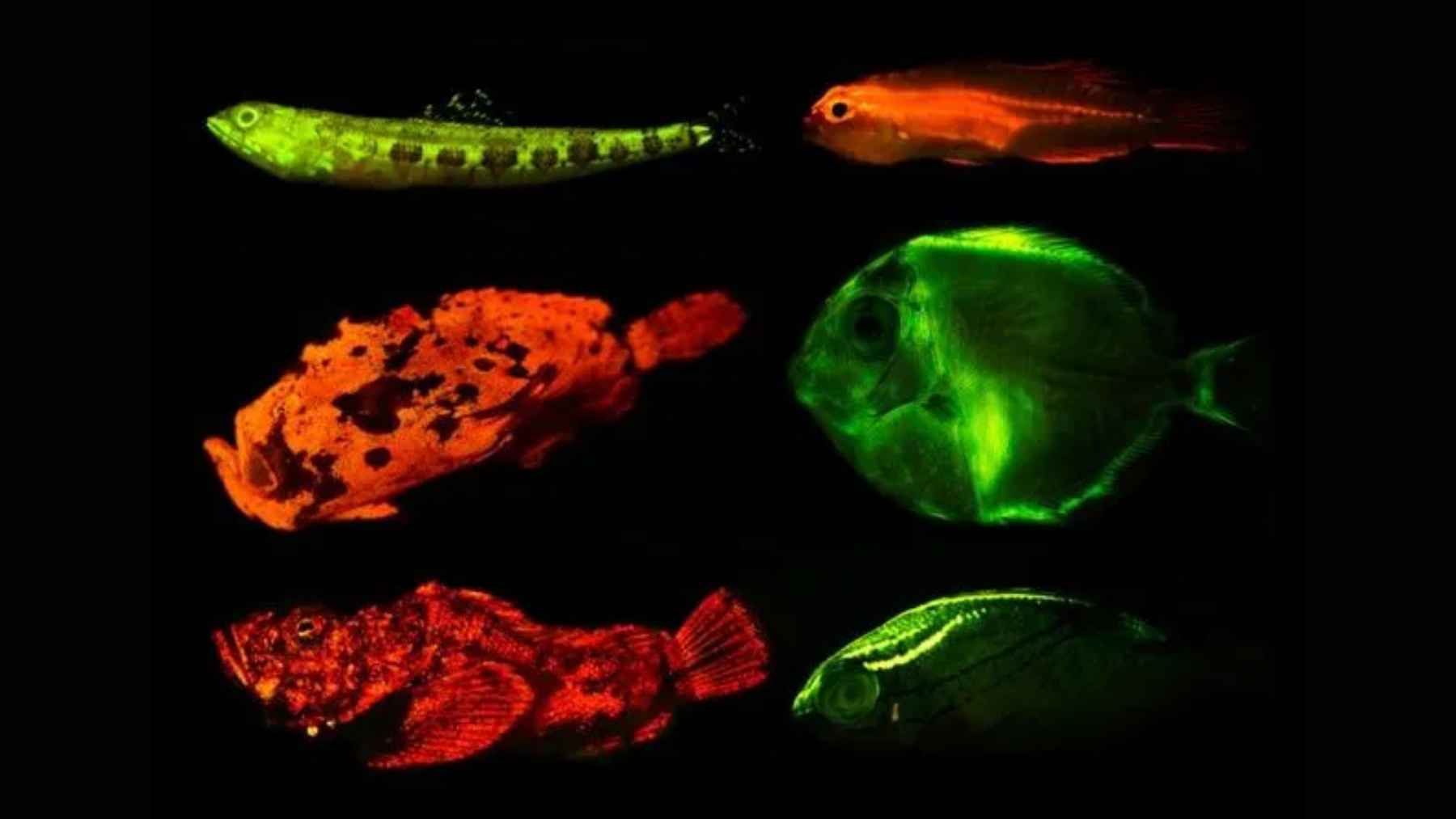

Hundreds of marine fish have been glowing underwater for centuries… and no one had noticed

Fish have been glowing in the dark seas longer than humans have walked on land……

Mobility

Driver’s licenses for people over 70 in California are expiring, and they must now appear in person every five years or they will be breaking the law

Most older Californians rely on their car for everyday life, from grocery runs to doctors’ visits. In…..

Goodbye to BMW, Mercedes, and Volkswagen: an economist warns that these brands could disappear before 2030

The idea sounds unthinkable at first glance. What if the German giants that fill European highways with…..

What many people install to protect their cars can now result in fines of $1,000 or even arrests

Energy

NASA conducts the first test of its nuclear engine for interstellar travel

Economy

Millions of people could lose their food this month following the implementation of a controversial law requiring 80 hours of work to retain SNAP benefits

New work rules for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program are starting to hit home in…..

A list reveals that three countries are among the most indebted in the world in 2025, with figures exceeding 120% of GDP

Public debt rarely makes front page news compared with inflation or jobs, yet it quietly…..

The longest tunnel in Latin America took more than 10 years to build and now connects two key regions that were previously isolated by mountains

High in the central Andes, a new piece of concrete and steel is changing how…..

The United States and Japan want to spend $550 billion on synthetic diamonds, which says a lot about the problem with China

For most people, diamonds mean engagement rings and glittering store windows, not chip factories and…..

An iconic Chicago candy factory with nearly 100 years of history has filed for bankruptcy and could close permanently after losing millions

One of Chicago’s oldest candy makers has landed in bankruptcy court. Primrose Candy Company, a…..

China directly threatens Panama for canceling historic port contracts signed in the 1990s and warns that it will pay a high political and economic price if it does not rectify the situation

At the center of the latest clash between China and Panama sits the Panama Canal,…..

A renowned airline just accidentally discovered that it had a Boeing plane abandoned at an airport since 2012 and no one at the company had noticed for over a decade

We all misplace our keys or forget an old subscription. But an entire jetliner slipping…..

All U.S. Social Security numbers may need to be changed following a massive breach that is already being investigated as a national threat

Every American who has ever had a Social Security number may now be living with…..

Goodbye to loans for non-citizens: the 2026 measure that could change the landscape of entrepreneurship in the US (and it’s not the first time this has happened)

A rule change in Washington, D.C. is about to hit many of the people opening…..

Chinese geologists make history: they discover a deposit buried 3,000 meters underground with more gold than South Africa’s reserves, which could be worth more than a country’s total GDP

Deep under the hills of central China, geologists say they have located more than one…..

Technology

The United States fires a laser from the ground that keeps a drone in the air for hours without having to land even once

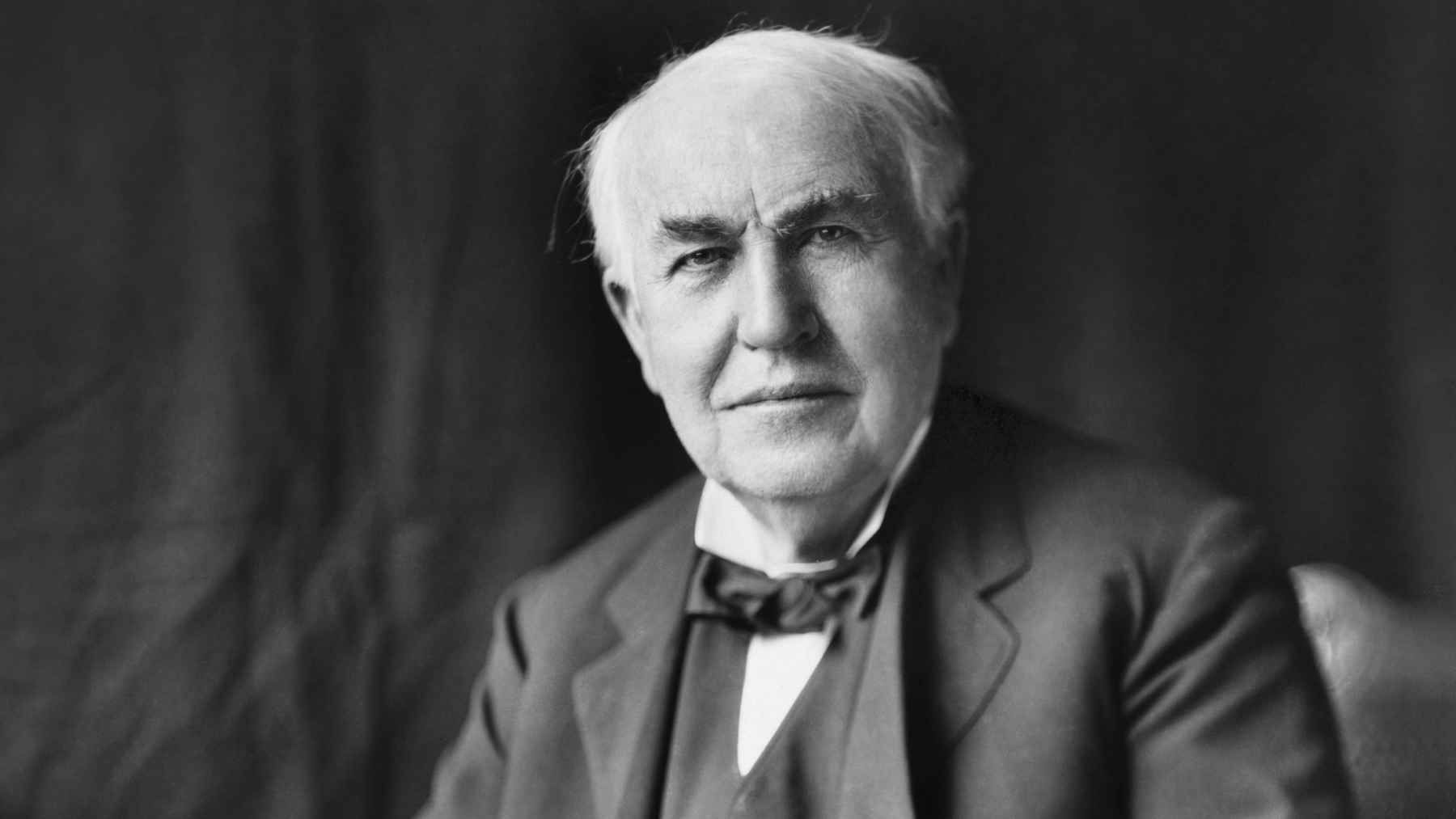

Thomas Edison may have created graphene without knowing it in 1879, and modern science has just discovered it almost 150 years later

A bat-shaped aircraft could be the next US fighter jet: it promises to fly at Mach 4 and coordinate drones from aircraft carriers

Goodbye to chemical rockets: scientists propose an idea that would allow interstellar travel in just 40 years using beams of electrons traveling at close to the speed of light.

Goodbye to nuclear submarines: Australia signed a $368 billion deal with the United States to receive them, but a new congressional report makes it clear that they may never arrive

This little-known trick turns old television sockets into an ultra-fast cable Internet connection without the need for construction work or technicians

Environment

He is only 14 years old, used a 10-year-old camera, and won the world’s most important macro photography contest with a photo of bees in India

Young wildlife photographer Rithved Girish has been named Young Close‑up Photographer of the Year 7…..

Goodbye to the myth that otters do not live in central Texas: a real estate agent discovers four swimming freely in a Hill Country lake

A short real estate video has turned into an unexpected conservation headline. While filming an…..

This tree bears sweet fruit in summer, does not break the soil with its roots, and is drought-resistant even when planted in a small garden

If you live in a small house or apartment with a tiny patio, choosing a…..

Microbes frozen since the Ice Age wake up and start devouring carbon in Alaska laboratories

Microbes that have been frozen in Arctic permafrost for tens of thousands of years are…..

For seven years, he collected more than 450,000 cans and bottles without knowing that this gesture would end up becoming the down payment on his first home

In Australia, an everyday recycling habit has turned into both a cleaner coastline and the…..

They spent the deadliest winter of the 17th century in a makeshift cabin eating whale blubber, not knowing if anyone would ever come back to rescue them

Almost four hundred years ago, eight English sailors spent a winter stranded on the shores…..

For the first time, an invasive species capable of destroying freshwater ecosystems in just a few months has been detected in Northern Ireland, and no one knows how to stop it

Tiny shellfish that most people would never notice have triggered a major warning in Northern…..

He created a lake to raise fish and installed cameras to monitor them, but ended up attracting eagles, deer, and owls to one of the continent’s most unexpected wildlife sanctuaries

It was supposed to be a straightforward farm project. Dig a five-acre lake, raise tiger…..

Trending

If you write using a mixture of upper and lower case letters within the same word, this is what your brain could be revealing, according to psychologists

Colombia has just broken all traditional family patterns with a statistic that surprises even Europe: 87% of babies are born outside of marriage, and this is only the beginning

They look like shiny cabbages and seem like something you would find at your grandmother’s house, but they are more fashionable than ever, and this supermarket sells them for less than $13

Scientists discover that defecating too often or too little could affect the microbiota and filter toxic substances into the blood

Stephen Hawking, scientist: “I don’t think humanity will survive the next thousand years, at least not without expanding into space”