Far to the north, under Greenland’s bright ice sheet, lies one of the most valuable collections of natural resources on the planet. Geologists say the island holds large reserves of lithium, rare earth elements and huge volumes of oil and gas that are central to batteries, wind turbines and other clean-energy technologies.

At the same time, global powers are looking north with growing intensity. So what happens when the world’s hunger for green technology meets a fragile Arctic landscape already under climate stress?

Recent work by researchers shows just how big the prize could be. Three rare earth deposits buried under the ice are thought to be among the largest on Earth and could supply key components for batteries and electrical systems that support the global shift away from fossil fuels.

The United States Geological Survey estimates that onshore northeast Greenland, including areas still covered by ice, may contain about 31 billion barrels of oil equivalent in hydrocarbons, a figure similar to all proven crude oil reserves in the United States. And that is only in the small fraction of the island that has been studied so far.

An island shaped for resources

Greenland’s geology is unusually rich because the island has experienced almost every kind of process that creates mineral wealth. Over four billion years, the crust was squeezed into mountains, pulled apart into rift valleys and pierced by volcanic intrusions. Those forces opened fractures where gold, rubies and graphite could collect.

Graphite is a key ingredient for lithium ion batteries yet the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland still describes it as “underexplored” compared with major producers such as China and South Korea.

Sedimentary basins on land, like the Jameson Land Basin, appear to hold the best prospects for oil and gas and are often compared to Norway’s hydrocarbon-rich continental shelf. Metals such as lead, copper, iron and zinc have been mined in small amounts since the late-18th century. So beneath a landscape that looks empty from the air, the bedrock is anything but simple.

Rare earths for your car, phone and wind farm

Some of the most strategically important elements in Greenland are rare earths such as neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium and terbium. These are vital for the powerful permanent magnets used in electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators and many of the electronics that quietly run in our homes and offices.

Scientists estimate that sub-ice deposits of dysprosium and neodymium in Greenland alone could cover more than one-quarter of projected future global demand, close to forty million metric tons.

One southern project, Kvanefjeld, is widely described as one of the largest undeveloped rare earth deposits in the world and could, in theory, supply around ten to fifteen percent of the current global rare-earth market once fully built.

Yet development has stalled after Greenland passed a law that effectively bans uranium-rich projects, reflecting deep local concern about radioactive waste near the town of Narsaq. That conflict has already triggered an international legal battle over compensation, showing how difficult it is to balance global demand for clean tech minerals with the safety of nearby communities.

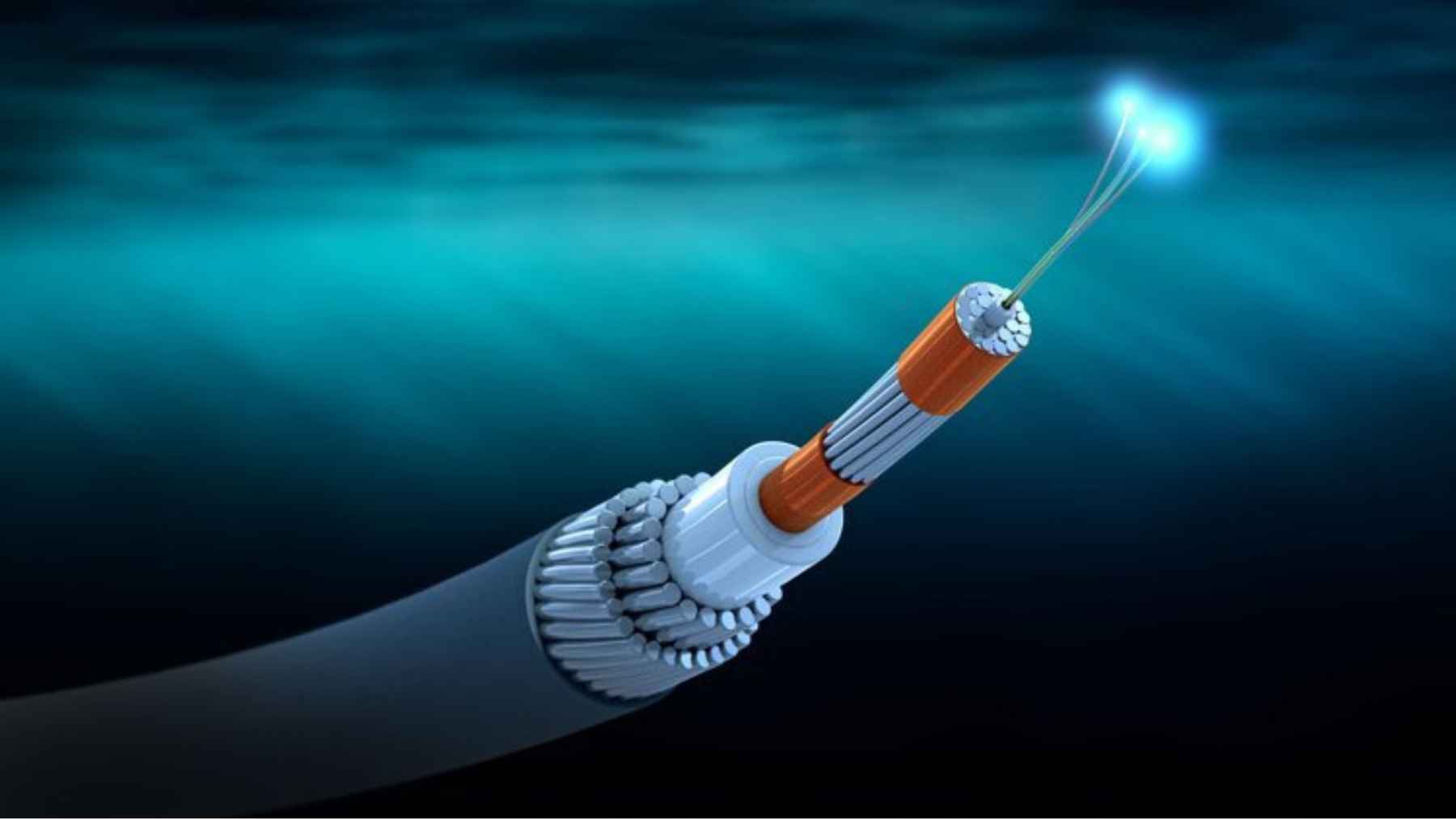

Outside Greenland, the scramble for these materials is driven by geopolitics as much as climate goals. China currently controls around seventy percent of rare earth production and about ninety percent of processing capacity, and it tightened export controls again in late 2025. Analysts note that Greenland hosts twenty five of the thirty four minerals the European Union classifies as “critical raw materials.”

That helps explain why United States president Donald Trump has talked about acquiring Greenland “the easy way or the hard way” and even “whether they like it or not,” and why officials around him have openly mentioned military options. For a quiet island of around 57,000 people, that is a lot of attention.

Melting ice, rising pressure

There is another twist. The same warming that is pushing governments toward low-carbon technology is also peeling back Greenland’s ice and making more of these resources reachable. Since the mid-1990s, an area of ice roughly the size of Albania has disappeared from Greenland.

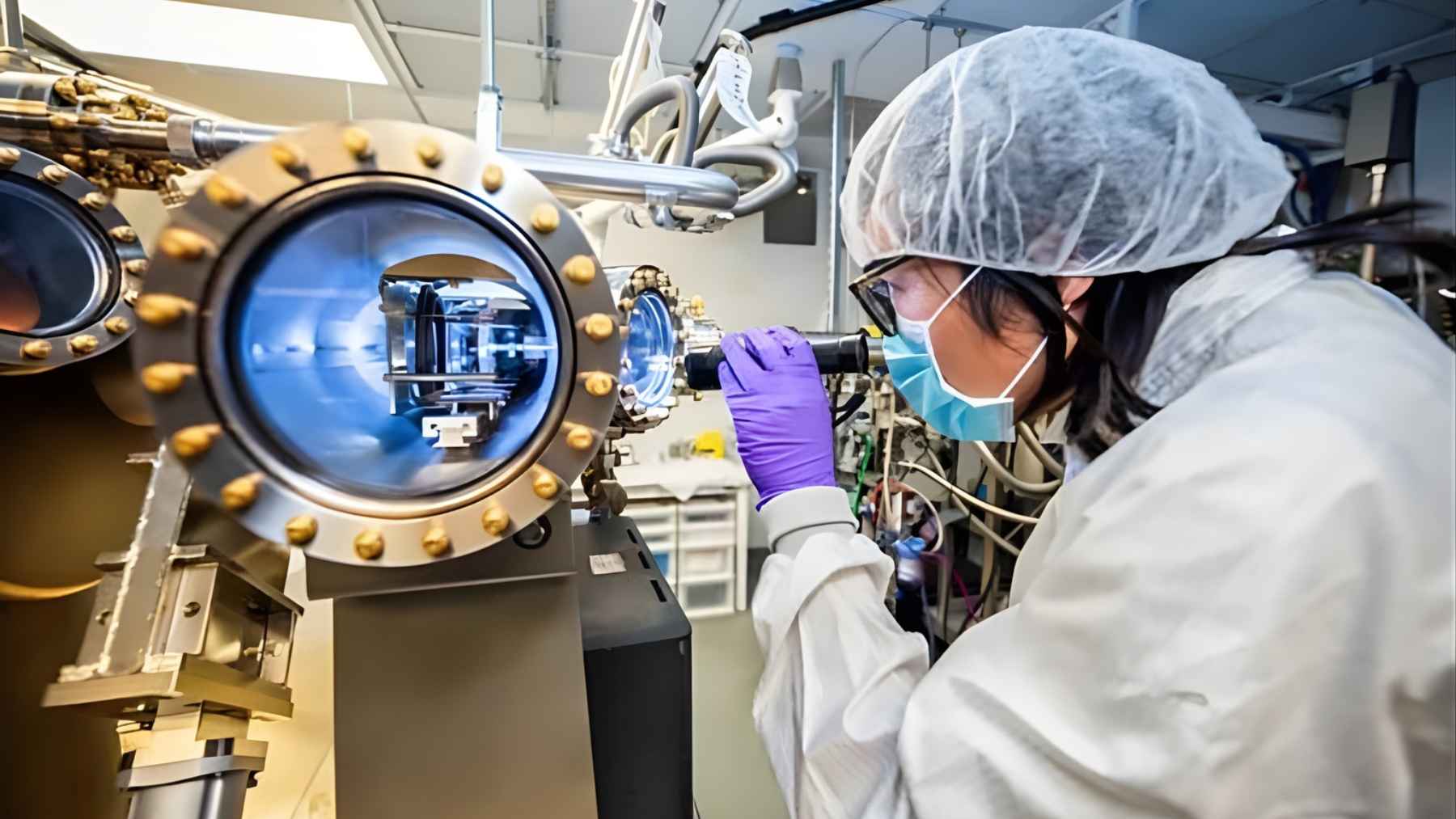

New tools such as ground-penetrating radar now allow scientists to map bedrock through up to two kilometers of ice and to identify potential ore bodies hidden below.

Prospecting under the ice remains slow and extremely expensive, and any truly sustainable extraction will be slower still. Greenland’s government currently regulates mining through strict legal frameworks created in the 1970s, but researchers expect pressure to ease those rules and issue new exploration licenses as global interest grows, especially from the United States. At the end of the day, the island faces a choice that is bigger than any single mine.

A choice that reaches beyond Greenland

Should Greenland accelerate extraction of its “green gold” to speed up the world’s shift away from fossil fuels, even if that means more open pits, more shipping and more risk for Arctic ecosystems already under stress? Or should it hold back and protect its landscapes, even if that slows down new supply of the very materials needed for cleaner cars and wind power and, in the long run, lower electric bills elsewhere?

Experts increasingly describe this as a global dilemma rather than a local one. Every phone in a pocket, every quiet electric bus in a traffic jam and every offshore wind farm spinning through a sticky summer heat wave draws on minerals from somewhere.

If the world chooses to tap Greenland more aggressively, it will need strong rules, transparent benefits for Greenlanders and firm protections for land, water and ice. Otherwise, the green transition risks looking a lot less green when viewed from Nuuk’s harbor or from a melting glacier edge.