For more than a century, fossil bones from the cliffs of southwest England were labeled as reptile limbs or random fragments. A new study shows that many of them actually belonged to coelacanths, the famous “living fossil” fish, revealing a thriving community of large predators in British seas about 200 million years ago.

The research, led by Jacob Quinn at the University of Bristol and published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, greatly expands the known record of British Triassic coelacanths. “From just four previous reports of coelacanths from the British Triassic, we now have over fifty,” Quinn explained. The fossils come from the latest Triassic Rhaetian stage, just before the end Triassic mass extinction.

Coelacanths are lobe finned fishes that first appeared in the Devonian and famously resurfaced in 1938 when a living specimen was netted off South Africa. Their overall body plan has changed very little through time, which is why they are often described as “living fossils”. Yet the new study shows they were far from rare in Late Triassic seas.

Quinn first spotted the mistake while studying Pachystropheus, a small marine reptile from the same rocks. Some bones did not fit reptile anatomy but matched coelacanth skulls and jaws. Once that key was in place, he and his colleagues re-examined museum drawers in Bath, Bristol, London and Cardiff.

Specimens registered as “indeterminate reptile”, “Ceratodus skull roof” or even mammal phalanges turned out to be parts of coelacanths. “It is remarkable that some of these specimens had been sat in museum storage facilities, and even on public display, since the late 1800s,” Quinn said.

To confirm the identifications, the team used micro CT scans on selected fossils. The scans revealed internal canals for nerves and blood vessels, as well as cartilage capped joint surfaces, that are characteristic of coelacanth braincases and jaws.

Most of the bones belong to the extinct family Mawsoniidae, relatives of today’s deep sea Latimeria that preferred nearshore, often brackish waters. A few elements likely represent members of the Latimeriidae, the group that includes the living species.

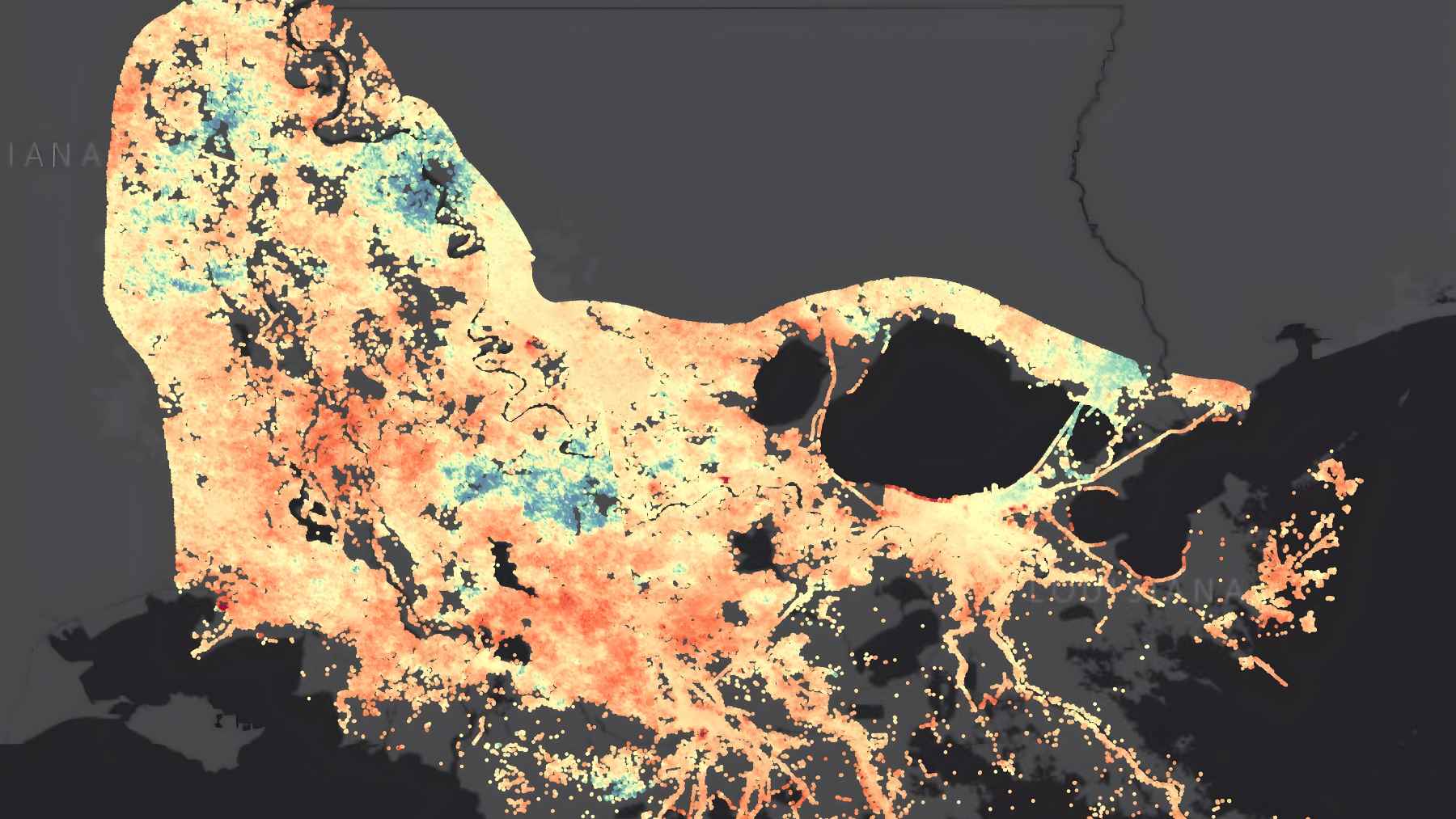

The fossils come mainly from the Westbury Formation around the Bristol Channel and from sediment filled fissures at Holwell in Somerset. In the Late Triassic this region formed the Bristol archipelago, a cluster of limestone islands in a shallow tropical sea. Sediment studies show fluctuating water depths and episodes of low oxygen on the seafloor, as well as pulses of plant debris washed in from nearby wetlands.

Within this setting the coelacanths shared the ecosystem with sharks, bony fishes, placodont reptiles and large predators such as ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs. The new bones show a broad range of sizes and shapes.

There are robust lower jaw elements, finely ornamented skull roof pieces, and a massive clavicle comparable in size to that of the Cretaceous giant Mawsonia gigas, which reached roughly one and a half meters in length. Co author Pablo Toriño noted that the material represents individuals of different ages, sizes and probably several species, hinting at a complex community structure.

The work also feeds into a larger picture of coelacanth evolution. Related mawsoniid forms are already known from Triassic rocks in France and Germany and from later deposits elsewhere. The British material shows that large bodied mawsoniids had already colonized brackish, storm influenced shelf seas on the eve of the end Triassic crisis, helping scientists trace how this long lived group spread between continents and environments.

There is a quieter message too. Many of these fossils sat for more than 150 years in museum drawers or even in public displays, hidden in plain sight because they were given the wrong label. By combining careful anatomical work with modern imaging, researchers have turned old collections into new environmental archives.

These ancient coelacanths help scientists reconstruct how coastal ecosystems responded to rising seas and ecological stress in the past, offering useful clues as we try to understand how marine life will cope with rapid change today.