Deep in Uganda’s Budongo Forest, wild chimpanzees are doing something that looks uncannily familiar. When they get hurt, they clean their wounds, apply chewed leaves and even help pull snares off one another. In some cases they tend to injuries on chimps that are not close relatives, behaving a bit like field medics in the treetops.

A new study pulls together more than thirty years of observations from two chimp communities called Sonso and Waibira. The team documented thirty four cases of self care and seven cases where chimps treated another individual. That may sound like a small number, yet for rare behaviors in a long-lived species it is a rich record.

Forest first aid

So what does chimpanzee first aid actually look like in daily life?

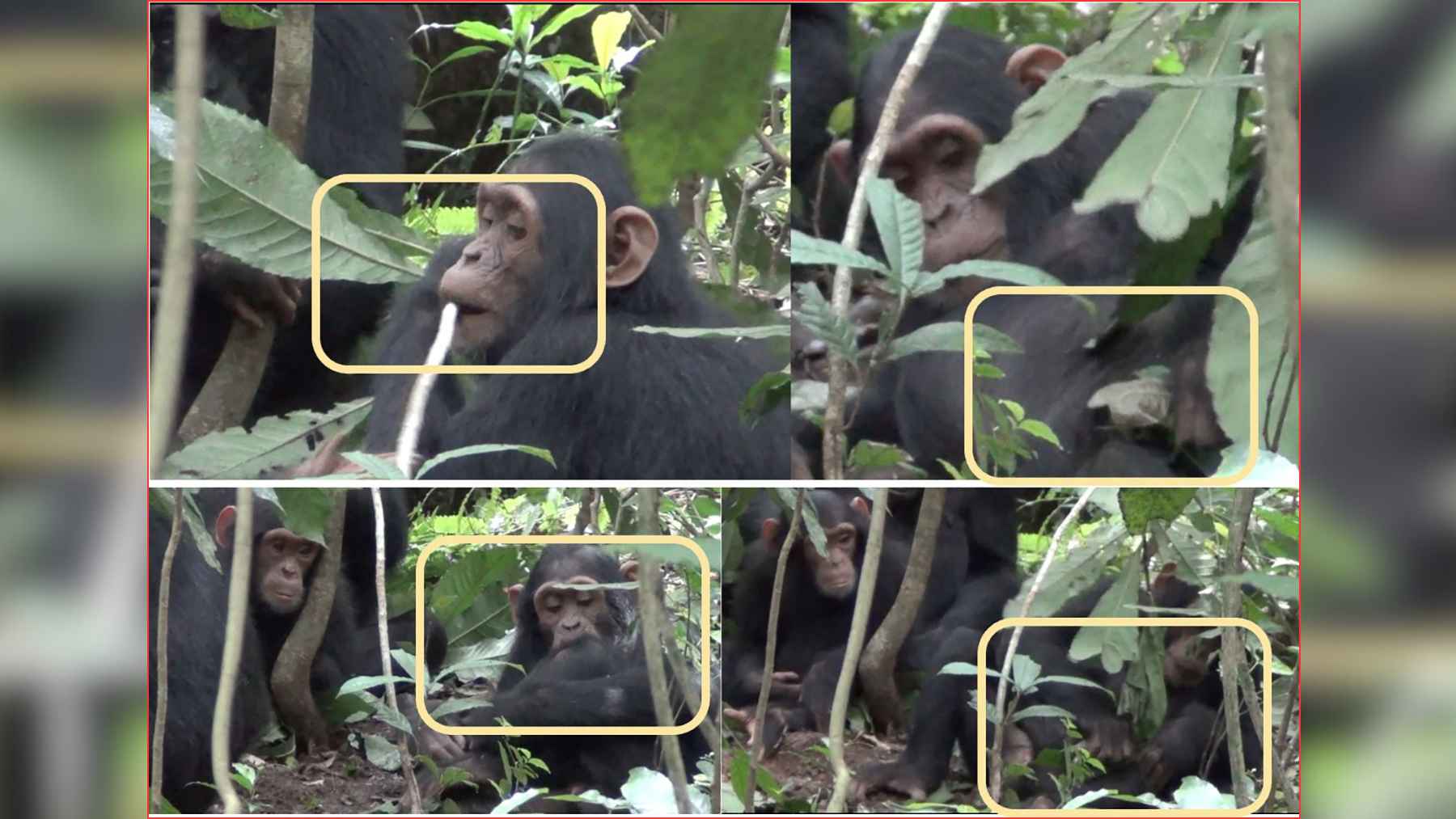

Researchers describe several techniques. Chimps lick their own wounds, lick their fingers and press them into cuts, dab injuries with carefully folded leaves, or chew bits of plant and press the moist pulp directly onto open skin. All of these actions were seen in the Budongo chimps.

Most events involved injuries from fights inside the group or from human-set snares that were meant for antelope but caught chimps by accident. In the Sonso community, about 40% of known individuals have at some point carried a snare injury, a stark reminder of how close conservation and health are for these animals.

The study also recorded hygiene routines that sound surprisingly human. Some chimps used leaves to wipe their genitals after mating or to clean themselves after defecation. One juvenile even removed a snare wrapped around its own limb.

Medicine on the menu

More than half of all self care and prosocial care events used plants.

The chimps did not pick leaves at random. They favored species such as Acalypha, Pseudospondias microcarpa and Alchornea floribunda. In African traditional medicine, these plants are used to treat wounds and ulcers, and lab tests show antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory effects.

In one striking sequence, an injured chimp chewed the bark of Argomuellera macrophylla, dabbed its knee with the attached leaves, then pressed the chewed material straight into the wound. Another chimp later used what appears to be the same plant while treating her mother. It looks very much like a learned recipe.

Do the animals understand the chemistry? Scientists are careful here. They suggest that chimps probably learn through experience and social observation which plants “work” without needing to know why at a molecular level. For the most part, the pattern is what matters. A sore limb, a familiar plant, careful application and then healing.

Caring for others

Perhaps the most eye-catching part of the study is what happens when the injury belongs to someone else.

Researchers recorded chimps licking another individual’s wounds, pressing their own fingers into cuts on a companion and applying chewed leaves to injuries on non-relatives. They also saw adults trying to free others from wire snares, a risky move when the metal can tighten or snap.

These are not quick grooming sessions. They look targeted, patient and focused on the injured area. That has led many experts to argue that the roots of empathy and caregiving may run deeper in our family tree than we once thought. At the same time, researchers caution that such prosocial acts remain rare, so they may require very specific social bonds or high levels of trust.

What this means for us and for them

For humans, the findings offer a glimpse of how healthcare might have begun long before hospitals, bandages or pharmacies. Ancestral apes probably faced the same problems we do today. Cuts become infected. Parasites spread. Group members get hurt in fights or by human traps. Reaching for the right leaf or helping a wounded neighbor could have made the difference between life and death.

For the chimps of Budongo, forest first aid is also a conservation issue. If snares continue to injure animals and key medicinal plants disappear through logging or climate stress, the community loses both bodies and knowledge. Protecting their habitat means protecting the quiet “clinics” that play out on branches and forest paths every day.

The study was published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.