The ocean’s depths have become the new front line in the geopolitical rivalry between China and the rest of the world. Beijing says its deep-sea ambitions are solely for scientific research and resource extraction. Still, experts have warned that the missions could serve a dual purpose by providing China with more excellent military capabilities. The murky intersection of academic, commercial, and military pursuits raises urgent questions about Beijing’s fundamental aims.

China’s deep-sea missions’ dual purpose

The perceived justification for deep-sea research in China has sought polymetallic nodules, valuable mineral deposits crucial for various industries, including aerospace and defense. The vessel Dayang Hao recently returned from deep-sea prospecting. Kenyan, Argentinian, Nigerian, and Malaysian students sailed on the ship, researching oceanic conditions and participating in onboard recreational activities.

But beneath this benign facade lies a strategic current. “When they’re talking about sending submersibles, the people who plan this are thinking about minerals, but they’re also thinking about how to exploit the deep sea for military advantage,” said Alexander Gray, an official in the White House National Security Council in the Trump administration.

China’s national security law explicitly lists the international seabed as an area of strategic interest, while its Central Military Commission has recognized the deep sea as a new war front. The research needed for deep sea mining, mapping its angle, analyzing its acoustics, and devising high-pressure equipment is indistinguishable from the data required for underwater (just like this biggest underwater discovery in history) combat operations, such as submarine warfare.

The 863 Program: The funding of deep-sea research by China

China’s deep-sea work reflects the country’s historical fusion of academic, commercial, and military sectors. Major research projects, many of which have been funded through military programs such as a state-led national security technology initiative known as the 863 Program, have included those led by China Minmetals.

Chinese researchers and defense specialists have highlighted the military value of polymetallic nodules, especially for modern warfare and aerospace capabilities. In 2022, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) recognized the deep sea as a strategic opportunity, and the prospects for such missions have raised concern over their real motivation.

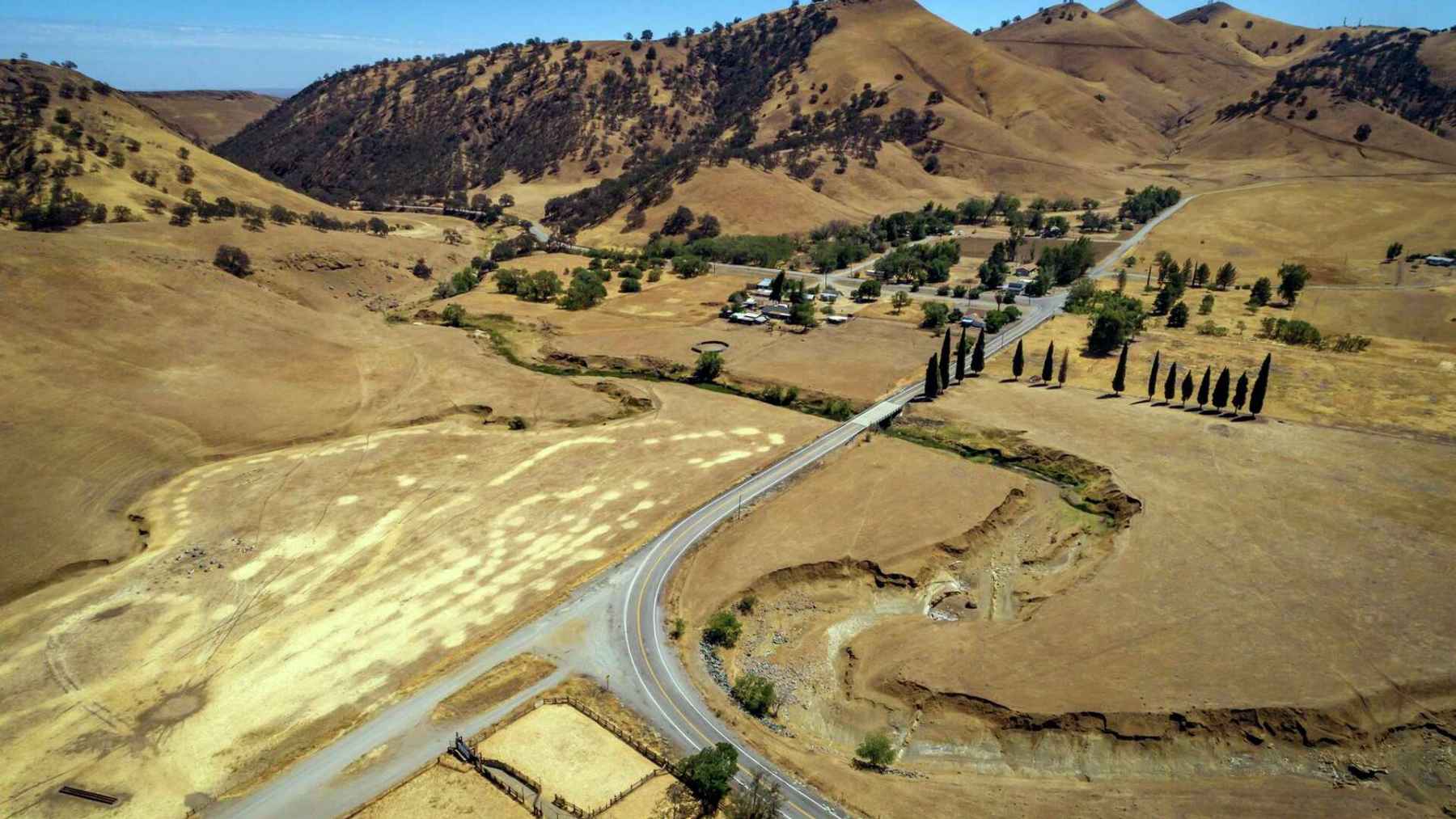

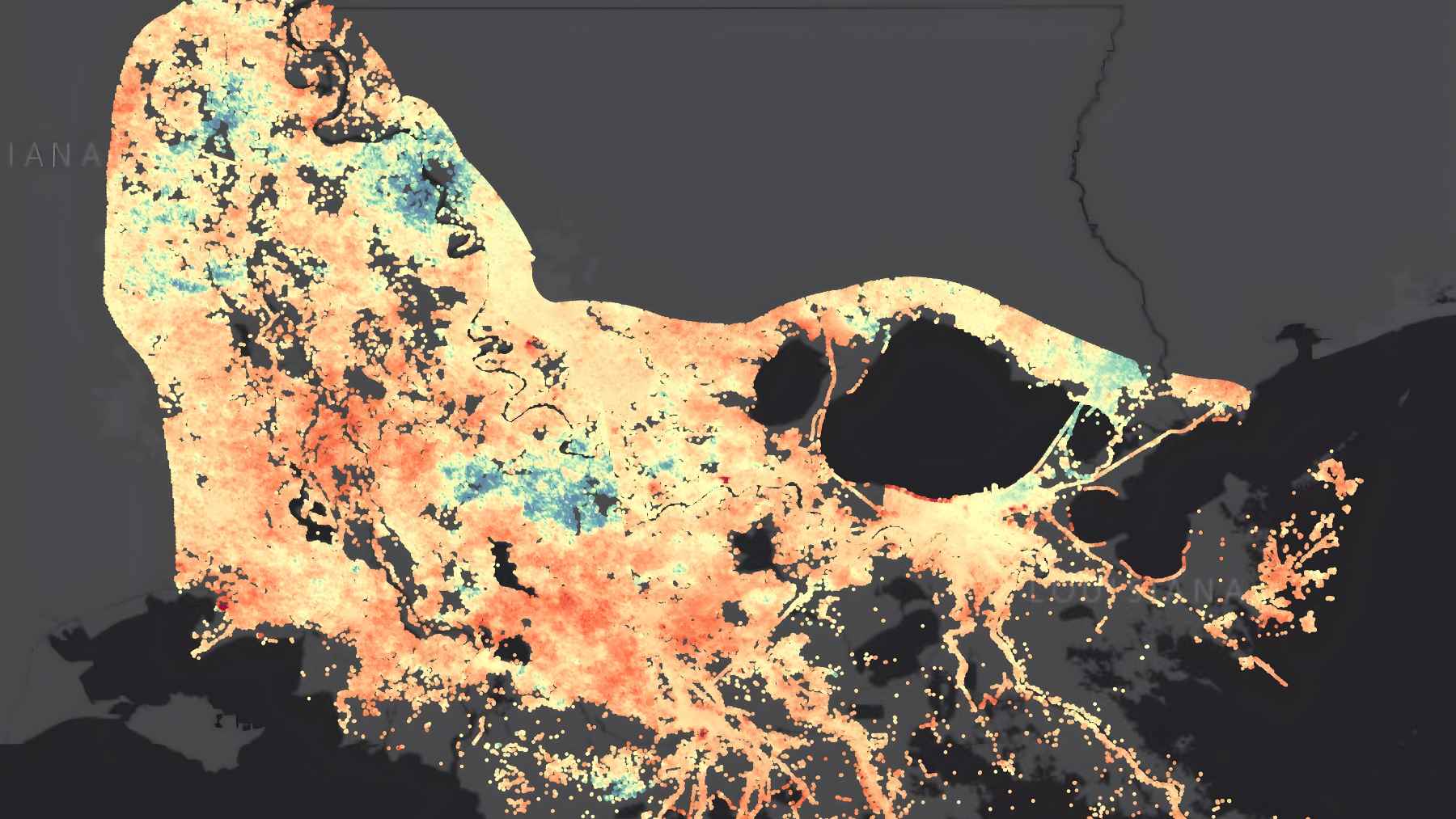

China’s deep-sea survey vessels have not limited their operations to their waters. Ship-tracking data compiled by Global Fishing Watch and the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory has revealed that other Chinese research vessels, like Dayang Hao, have also surveyed the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of the Philippines, Malaysia, Japan, Taiwan, Palau, and even the US.

One of the more troubling ships was the Kexue, which, in July and August 2022, spent 20 days at a time studying the seabed off the site of the contentious Scarborough Shoal, a flash point in the decades-old territorial dispute between China and the Philippines.

In a closely related development, Dayang Hao was also reported to be conducting seabed surveys and putting further pressure on regional tensions, this time near the Spratly Islands. Under international law, conducting research within another country’s EEZ without permission is illegal.

However, China’s large fleet of survey ships continues to sail through disputed waters, prompting many to believe they have scientific and military motives. “Most probably, a lot of these surveys are both scientific and military or commercial and military,” said Harrison Prétat, an associate director at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

Navigating conflicts: Chinese ship under scrutiny near Hawaii

In late 2021, suspicion grew that the Dayang Yihao, a sister ship of the Dayang Hao, left its assigned exploration site in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone and diverted into the US-exclusive economic zone near Hawaii. The ship traced a loop just south of Honolulu for five days before reverting to its original route. A US State Department spokesperson said China had not applied for permission to research US waters.

It speculates that this detour may have allowed China to gather intelligence about the seabed topography near Hawaii, which could help with naval operations and submarine movements. “The US would have concerns if just some state-owned vessels were nearby,” said Thomas Shugart, a former officer in the US Navy’s submarine warfare division.

As China ramped up its deep-sea research and mining activities, the geopolitical implications grew harder to overlook (like this second Amazon discovered underwater on Earth). The real motives behind Beijing’s massive state funding, military-supported research programs, and repeated incursions into foreign waters are being questioned. This ever-more-powerful convergence of scientific discovery and military strategy presents obstacles for China’s immediate neighbors and the global order.