Cracks racing through Antarctica’s “Doomsday Glacier” are turning a once stabilizing ice shelf into a liability, nudging part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet closer to retreat that would be very hard to stop.

Thwaites glacier “doomsday glacier” cracks in Antarctica

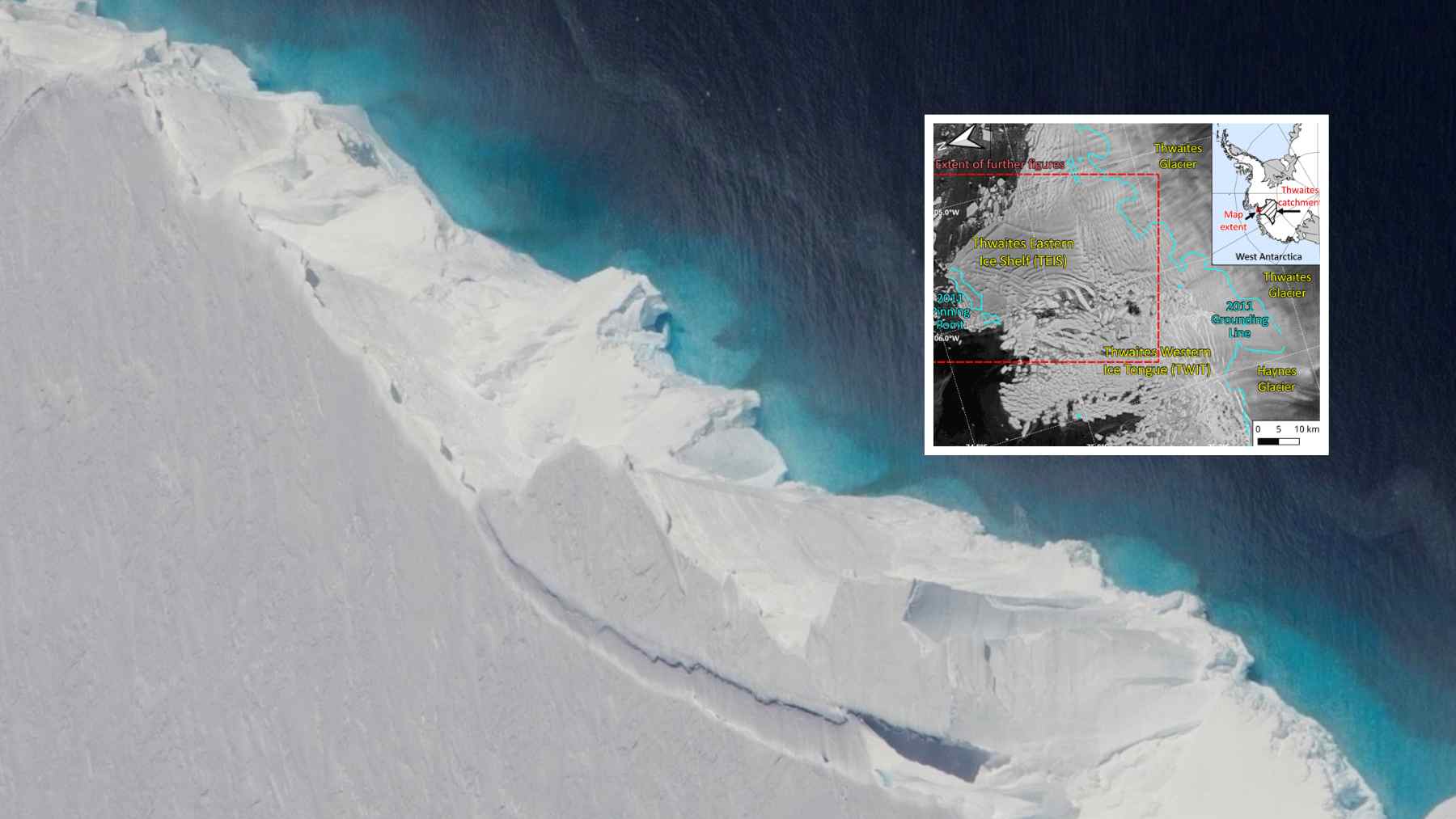

Thwaites Glacier sits in West Antarctica and covers an area roughly comparable to Florida. It sends more than 50 billion tons of ice into the ocean each year, about four percent of today’s global sea level rise. If the glacier ultimately collapses, scientists estimate it could raise sea level by up to 65 centimeters over the coming centuries.

Thwaites glacier sea level rise risk

The new alarm focuses on the Thwaites Eastern Ice Shelf, a floating tongue of ice that once acted like a safety net in front of the glacier. For years it was anchored on a ridge on the seafloor, known as a pinning point, which helped hold back the ice upstream.

A study led by researchers at the University of Manitoba traces how that safety net has frayed between 2002 and 2022 using satellite images, ice flow data, and GPS measurements.

Thwaites eastern ice shelf safety net and pinning point

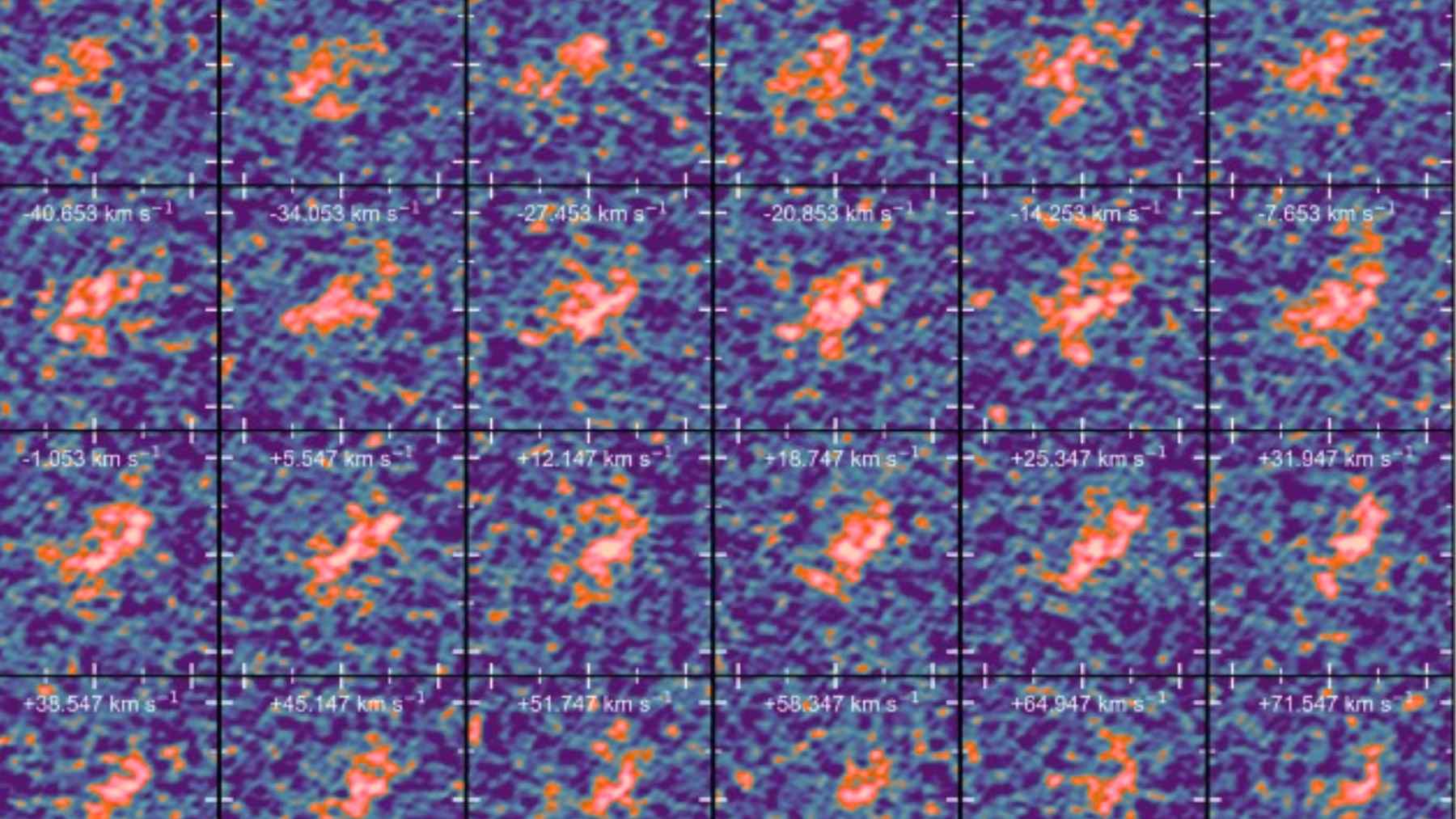

The team identified four stages in the shelf’s decline. First, long fractures opened along the direction of ice flow and crept eastward, some more than eight kilometers long and cutting across the shelf. Later, many shorter cracks appeared that cut across the flow.

Together they roughly doubled the total fracture length, from about 165 to about 336 kilometers.

Satellite images and GPS measurements track ice shelf fractures (2002–2022)

Stress in the shelf has shifted markedly, concentrating near the pinning point. By around 2017, key fractures had sliced completely through parts of the shelf, and the ice largely lost its grip on the underwater ridge. GPS instruments then recorded damage spreading upstream at about 55 kilometers per year and faster flow of ice inland.

Stress near the pinning point and faster ice flow inland

The researchers describe a feedback loop in which cracks weaken the shelf and let it move faster. The faster motion stretches the ice and opens more crevasses, which weakens the shelf again. Over time, the ridge that once braced the shelf starts to act more like a hinge.

Feedback loop: crevasses weakening the ice shelf

Why should someone far from Antarctica care about a remote shear zone in the ice. Because ice shelves act like corks in the neck of a bottle. They do not raise sea level much when they melt, since they already float. Their real job is to hold back the much thicker ice that still rests on land.

Why ice shelves matter for global sea level

Thwaites is especially vulnerable because it sits on a reverse slope bed, where the seafloor deepens inland. Once the grounding line that marks where the ice lifts off the bedrock begins to retreat into deeper water, the glacier tends to keep pulling back.

Earlier computer models suggested that parts of Thwaites could retreat by nearly one kilometer per year.

Grounding line retreat and reverse slope bed instability

The latest summary from the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration indicates that some of the most extreme ideas about sudden collapse this century are less likely than once feared. At the same time, their studies point to rapid ice loss that is already underway and likely to speed up through this century and the next.

The basic message is that Thwaites will keep adding to sea level, even if the exact timetable remains uncertain.

Coastal flooding and storm surge impacts for low-lying communities

For low-lying coastal communities, even a fraction of that 65 centimeter potential matters. Higher seas mean more frequent flooding on clear days and more damaging storm surges.

In cities from Miami to Lagos, that translates into repeated repairs, rising insurance costs, and hard decisions about which neighborhoods can be defended.

Climate action and coastal adaptation to slow ice loss

Thwaites will not decide our coastal future on its own. Other Antarctic glaciers, Greenland’s ice sheet, and the steady expansion of warming oceans all add to the total.

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions can still slow those combined changes, to a large extent, by limiting the ocean warming that is eating away at Antarctica’s ice from below.

At the end of the day, the new satellite record is an early warning that the safety nets at the ice edge are thinning and that the time for coastal adaptation and climate action is already short.

The study was published on the Journal of Geophysical Research (Earth Surface) website.