The air we breathe feels like the ultimate constant. You wake up, take a breath, and do not wonder whether oxygen will still be there tomorrow. Yet according to new work supported by NASA and led by researchers at Toho University and Georgia Tech, Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere is only a temporary chapter in the planet’s story, not the final one.

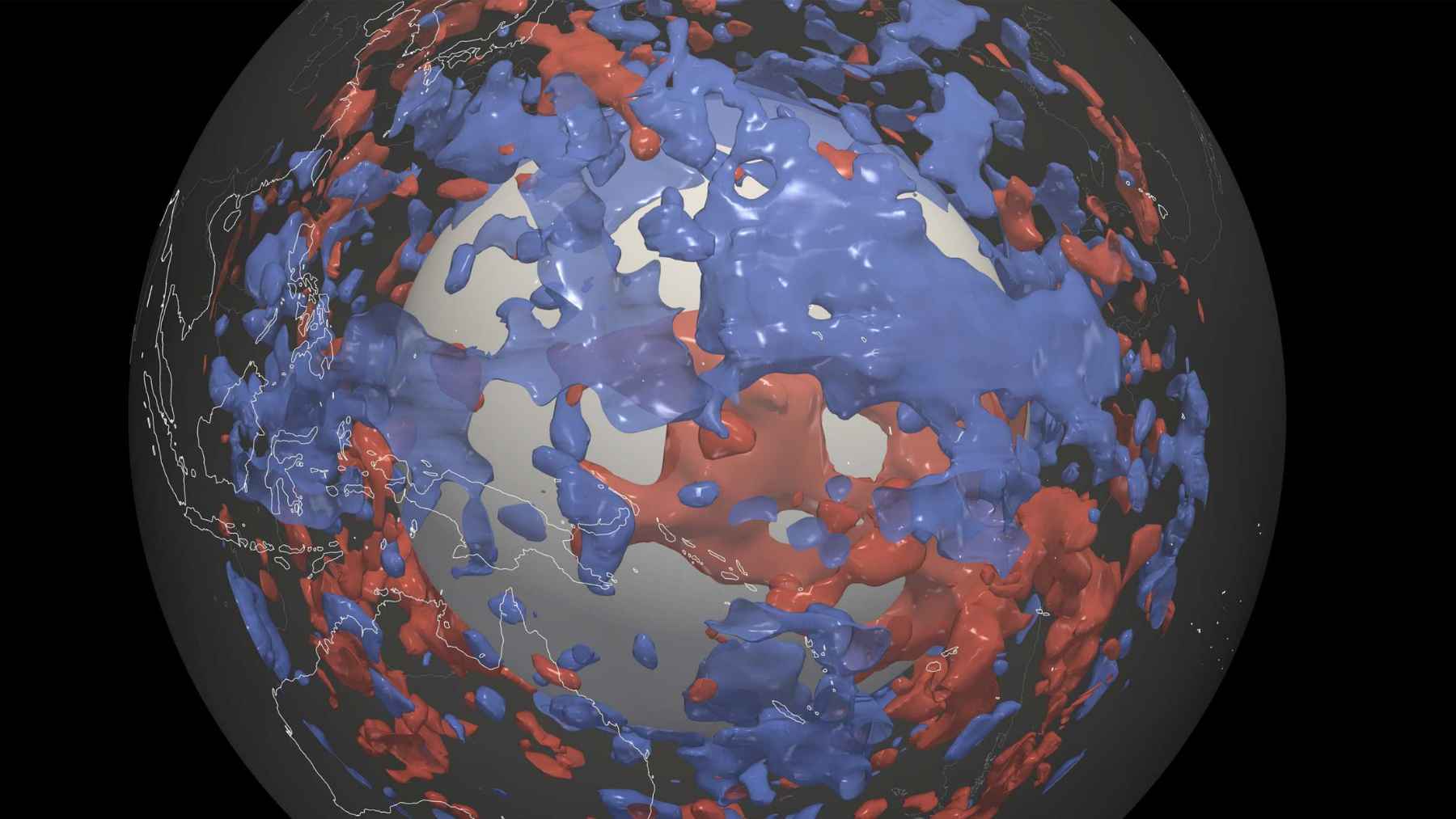

Using a sophisticated Earth system model and more than 400,000 computer simulations, the team estimated how long our planet can keep an atmosphere with oxygen levels similar to today. Their result points to a future lifespan of about one billion years for an oxygenated atmosphere with at least 1 percent of the current oxygen level, with an average of 1.08 billion years and some uncertainty on either side.

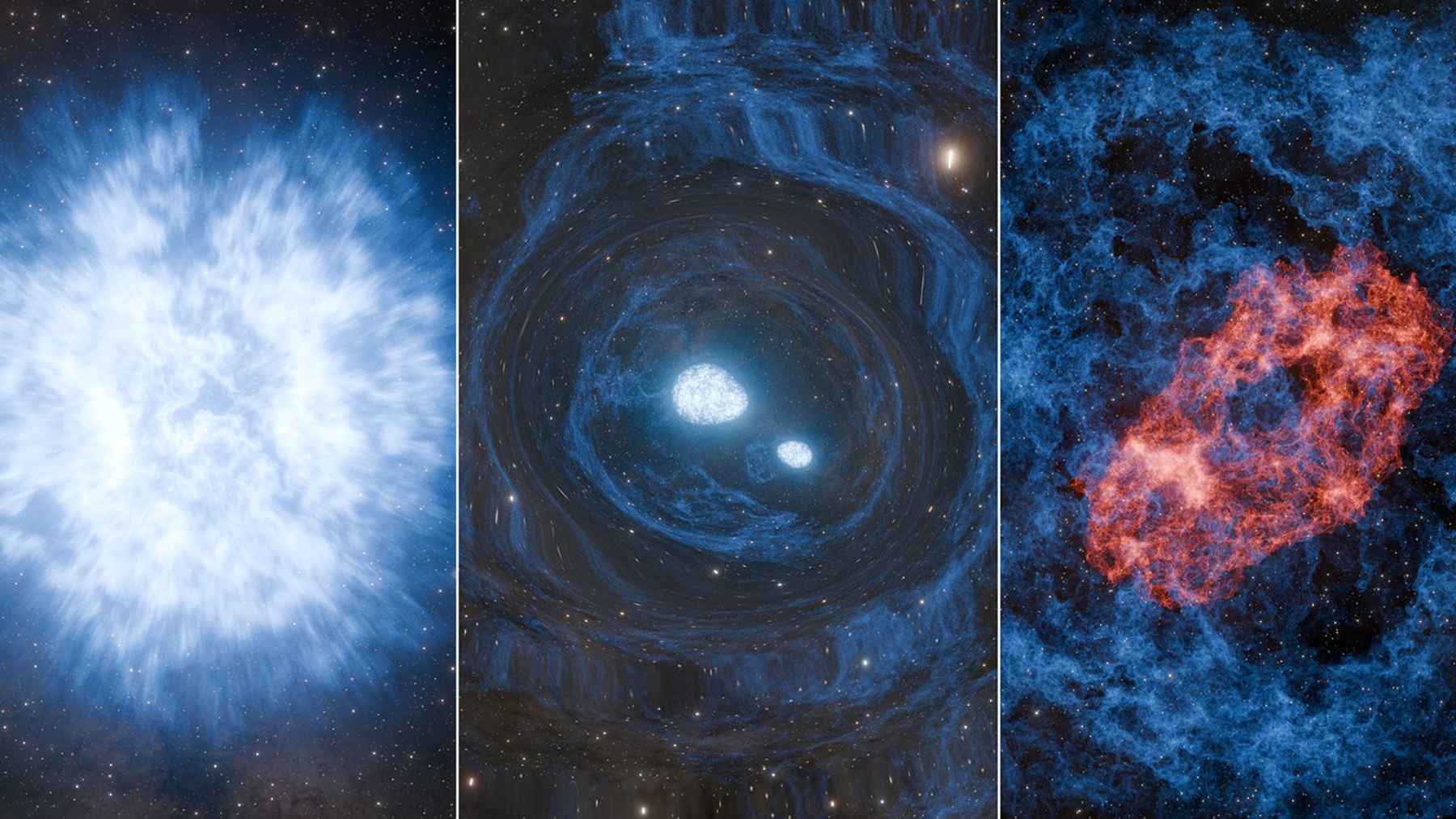

Great Oxidation Event and early Earth

After that, things change quickly in geological terms. The model suggests that once deoxygenation begins, atmospheric oxygen will crash to values similar to those on early Earth before the first big rise in oxygen known as the Great Oxidation Event. That ancient world was dominated by microbes that did not use oxygen at all.

Sun-driven climate shifts and carbon dioxide decline

What triggers this distant shift is not pollution or deforestation, but the slow brightening of the Sun. As solar radiation increases over hundreds of millions of years, it drives long-term changes in the carbon cycle.

More intense sunlight speeds up chemical weathering of rocks, which removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Lower carbon dioxide means plants eventually struggle to perform photosynthesis efficiently, so global oxygen production starts to fall.

Methane, ozone layer loss, and anaerobic life

At first, the drop would be gradual. Then the system crosses a threshold. The modeling shows a rapid transition to an oxygen-poor state where oxygen-breathing animals and plants can no longer survive.

In a news release, lead author Kazumi Ozaki explains that the post oxygen world would have more methane, very low carbon dioxide, and no protective ozone layer. In his words, the Earth system will probably become “a world of anaerobic life forms.”

Habitability is not forever

That picture sounds dramatic, but it plays out on timescales that dwarf human history. Modern humans have existed for roughly three hundred thousand years. Agriculture began only about ten thousand years ago.

Compared with a billion year countdown, our entire civilization fits in the tiniest sliver of the timeline. No one is warning that your grandchildren will suffocate. The study instead reminds us that even a “habitable” planet evolves, and that friendly conditions do not last forever.

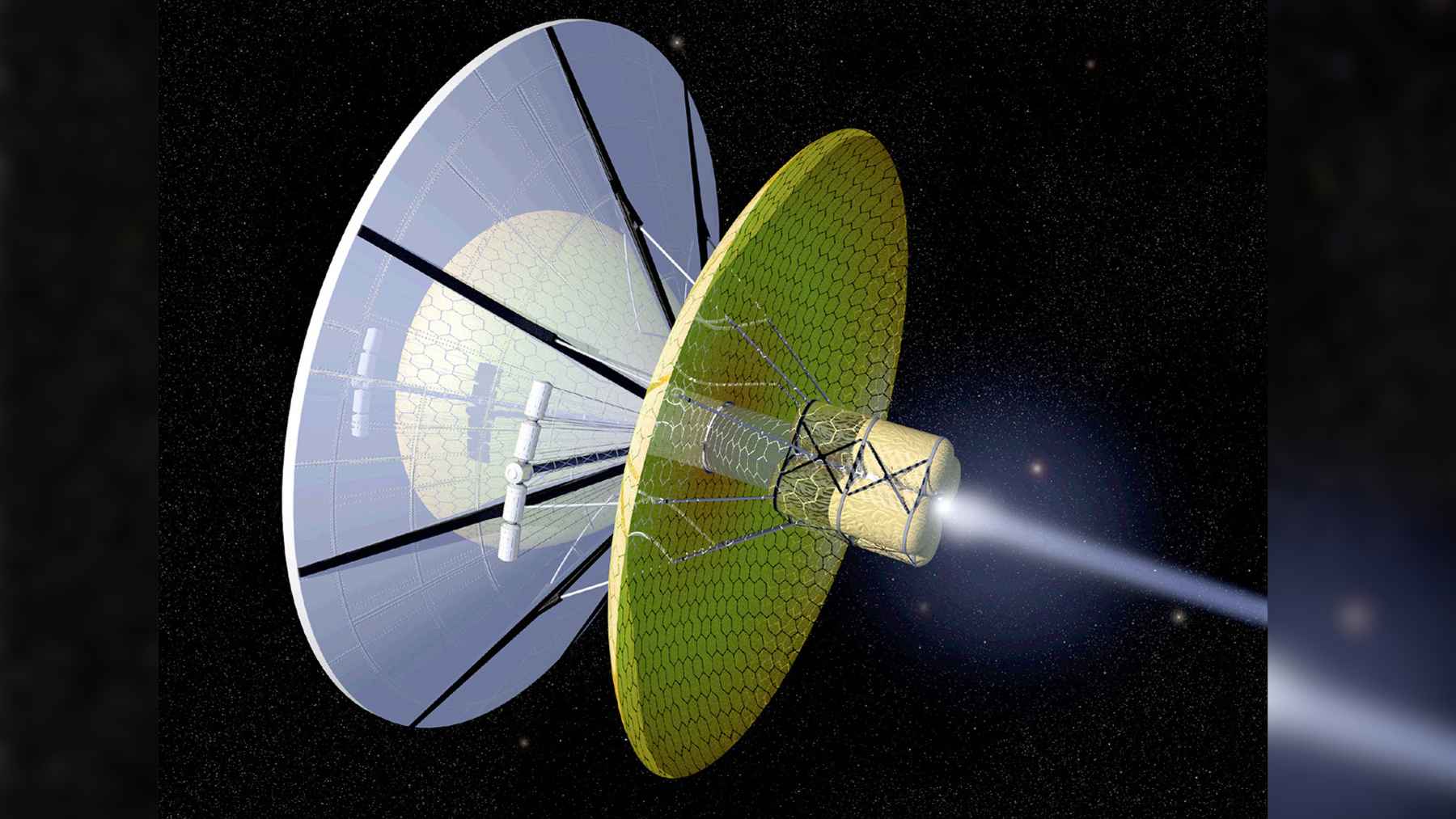

Exoplanets, biosignatures, and the search for life

So why does this far-future forecast matter now, beyond curiosity about cosmic endings? One reason is the search for life on other worlds. Oxygen and its byproduct ozone are often treated as the gold standard for biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres.

The new work suggests that an oxygen-rich phase may cover only about 20 to 30 percent of a planet’s total lifetime as an inhabited world. That means many living planets could be missed if telescopes look only for oxygen skies.

Earth’s atmosphere and the long-term carbon cycle

The study also highlights how tightly linked life and atmosphere really are. The same delicate mix of gases that determines how harsh a heatwave feels or how often we run the air conditioner also sets the outer limit for complex life on Earth.

In the very long run, the carbonate silicate cycle tends to push planets toward carbon dioxide scarcity, weaker photosynthesis, and finally oxygen collapse. Our world is not a static stage for life. It is an active partner.

The oxygen era and Earth’s future

This billion year deadline will not show up on any human calendar or electric bill. Long before the great deoxygenation, our species will either have solved its nearer-term environmental crises or been overwhelmed by them.

Yet the message from this work is quietly powerful. Habitability is not guaranteed. The oxygen era that lets animals, forests, and coral reefs exist is special in time as well as in space.

Distant worlds and planetary science

In the end, the research invites a double reflection. For planetary scientists, it is a prompt to widen the menu of biosignatures when scanning distant worlds. For everyone else, it is a reminder that the breathable sky outside the window is both fragile and finite, even if its ultimate transformation lies far beyond any human horizon.

The study was published on Nature Geoscience, which provides the main scientific reference for these findings.