In December 2025, the European Space Agency confirmed that its new P160C solid propellant rocket motor has passed its ground qualification review, officially declaring the booster ready for flight. The motor will give Ariane 6 and Vega families extra power to lift heavier payloads while Europe works to secure independent access to orbit.

At first glance, a new rocket motor might feel distant from everyday concerns. Yet these launchers carry satellites that track rising seas, monitor forests and support communication networks that quietly influence everything from farming decisions to the electric bill. A more capable booster, used wisely, can help pack more science and connectivity into each trip to space.

P160C and Europe’s race to stay in the launch game

The P160C is an extended version of the P120C booster that already flies on Ariane 6 and Vega C. According to French space agency CNES, the new motor is about one meter longer than its predecessor and is designed to hold roughly 14 extra tonnes of solid propellant, improving launcher performance by around ten percent for the same cost as CNES explains in a technical Q&A. That extra punch translates into more or heavier satellites per launch or the ability to send them to higher, more demanding orbits.

ESA plans to use the first four P160C units on a four booster Ariane 6 configuration scheduled to fly in 2026. Industrial teams in Europe and French Guiana are already preparing to ramp up production to at least 35 motors per year so regular Ariane 6 and future Vega C plus missions can tap the upgrade. At the end of the day, that is about keeping pace in a market where launch capacity is tight and demand for Earth observation and broadband keeps climbing.

How the booster is built and tested

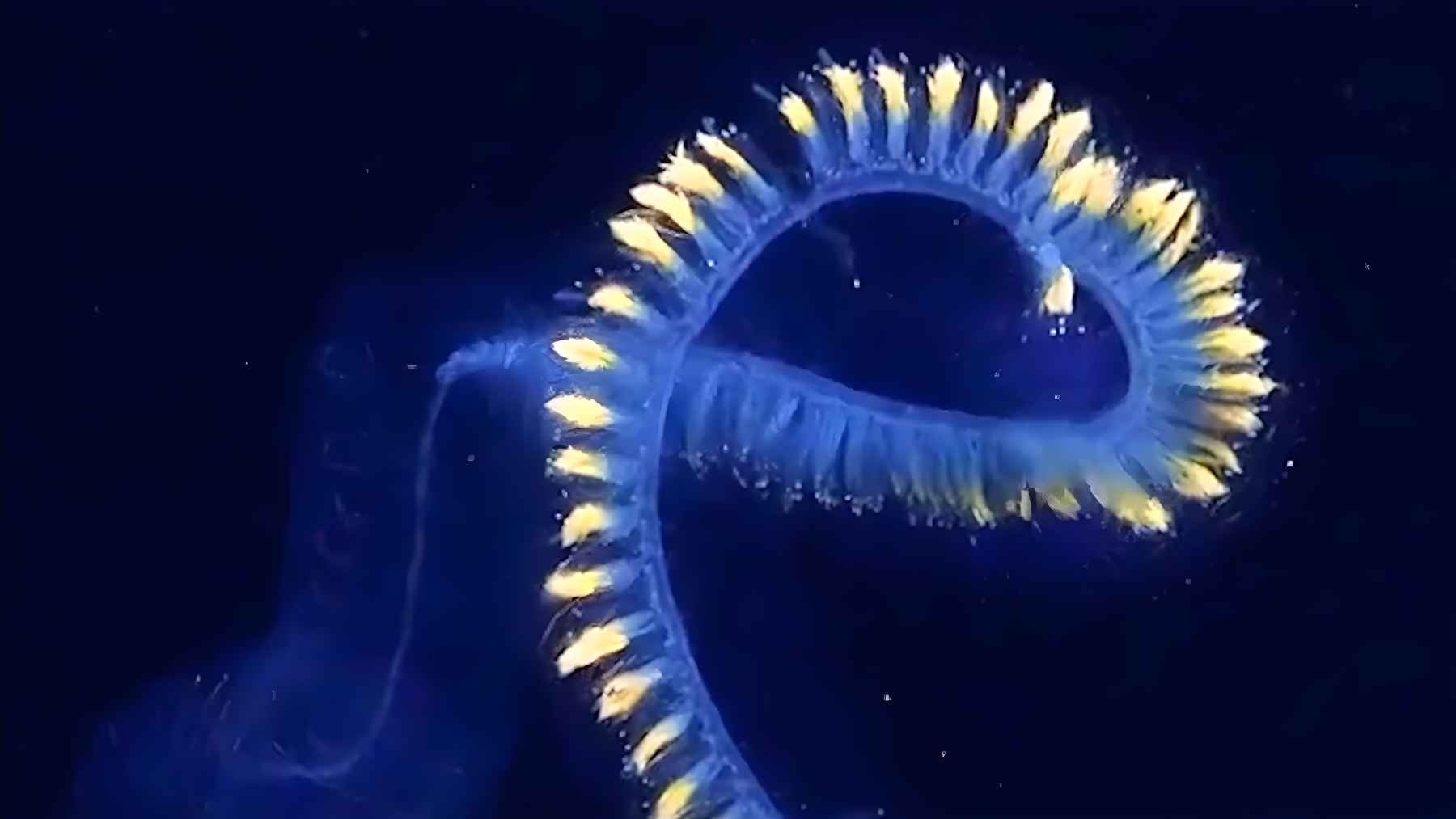

The P160C remains a single piece carbon fiber motor case produced by Avio in Colleferro near Rome and integrated through Europropulsion and joint facilities in French Guiana, a story ESA recently highlighted in its profile on Ariane 6 components made in Italy. The nozzle, built by ArianeGroup near Bordeaux, channels exhaust gases heated to around 3,000 degrees Celsius and can swivel to steer the launcher during flight.

YouTube: @esaextras

To qualify the design, engineers carried out a full duration hot fire on the BEAP test stand at Europe’s Spaceport in Kourou. Avio reports that the April 24 test in French Guiana ran for more than two minutes and confirmed that the longer casing and greater propellant load behave as expected. ESA’s Alessandro Ciucci described the December review that followed as a key checkpoint, noting that independent teams examined data and confirmed that the design is robust.

These tests are not simply about thrust. CNES underlines that each campaign at BEAP includes environmental monitoring with dozens of fixed and mobile sensors around the site to track air, water, flora and fauna during and after a firing. That approach reflects a growing awareness that rocket tests must consider local ecosystems along with performance numbers.

Mega constellations, climate missions and crowded orbits

More powerful boosters arrive at a moment when low Earth orbit is filling fast. ESA estimates that more than a million fragments of space debris now circle Earth, from spent rocket stages to shards from old collisions. Each new launch has to be weighed against the risk of adding to that cloud of junk.

At the same time, Europe’s upgraded launchers are tied to major commercial plans. Arianespace has a long-term agreement with Amazon to perform 18 Ariane 6 launches for the company’s global broadband constellation, with 16 of those flights reserved for a more powerful configuration that uses enhanced solid boosters as detailed in the launch contract. Amazon points out that this network, known as Project Kuiper, will rely heavily on European partners and is expected to support thousands of jobs and billions of euros in gross domestic product across the European Union according to its own economic impact analysis.

Scientists also depend on this extra lift. Earth observation missions and climate satellites will benefit from the ability to ride on heavier rockets. A recent example from another launch provider is the Sentinel 6 mission that tracks changing ocean heights, a type of satellite highlighted in reporting on sea level monitoring from orbit. For Europe, a stronger Ariane and Vega fleet can help keep similar missions flying without relying on foreign rockets.

Environmental trade-offs in a busier sky

The new motor’s extra capability is good news for payload planners but raises familiar questions about sustainability. Solid propellant boosters release combustion products directly into the upper atmosphere and their spent casings often become long lived objects in orbit. Events such as a decades old “zombie” satellite briefly waking up show how old hardware can still surprise scientists and complicate observations.

On top of that, the rise of large constellations is already worrying astronomers. ECONEWS has reported on proposals for thousands of reflective spacecraft that could brighten the night sky and disrupt observations, such as a planned mirror-based power project described as an astronomers’ nightmare of flying mirrors. Add in new quasi-moons and other small bodies that share Earth’s orbital neighborhood, including the recently confirmed quasi-moon 2025 PN7, and it becomes clear that our near space environment is getting more complex.

As P160C moves from test stand to launch pad, European agencies face a double task. They need to use the booster to keep climate missions and scientific observatories in orbit while also enforcing debris mitigation rules and investing in cleaner technologies on the ground and in space. For the most part, that balance will decide whether a more powerful launcher fleet simply fills low orbit faster or genuinely helps protect life back on Earth.

The official statement was published on ESA’s website.

Image credit: ESA-European Space Agency