If 24 hours already feel too short, imagine trying to fit your whole routine into just 19. According to new research, that was everyday reality on our planet for roughly a billion years in deep time.

A study published in Nature Geoscience finds that during the mid-Proterozoic era, between about 2 and 1 billion years ago, Earth’s day length stopped getting longer and stalled at around 19 hours. This unexpected pause appears to link the motion of the oceans and atmosphere with the slow rise of oxygen and the evolution of life during what geologists often call the “boring billion.”

At the heart of the story is a cosmic tug of war

Normally, Earth’s rotation gradually slows over time. The Moon pulls on our oceans, building tidal bulges that lag slightly behind our planet’s spin. That offset creates a torque that steals a bit of Earth’s rotational energy and hands it to the Moon. The Moon drifts outward, and our days creep longer.

The new work suggests that, for a long stretch of the Precambrian, that gentle braking was almost perfectly balanced by a second player. Solar heating drove powerful atmospheric tides that pushed in the opposite direction and slightly sped up Earth’s rotation. When these two torques matched, day length stopped changing and hovered near 19 hours.

A billion-year plateau in the length of day

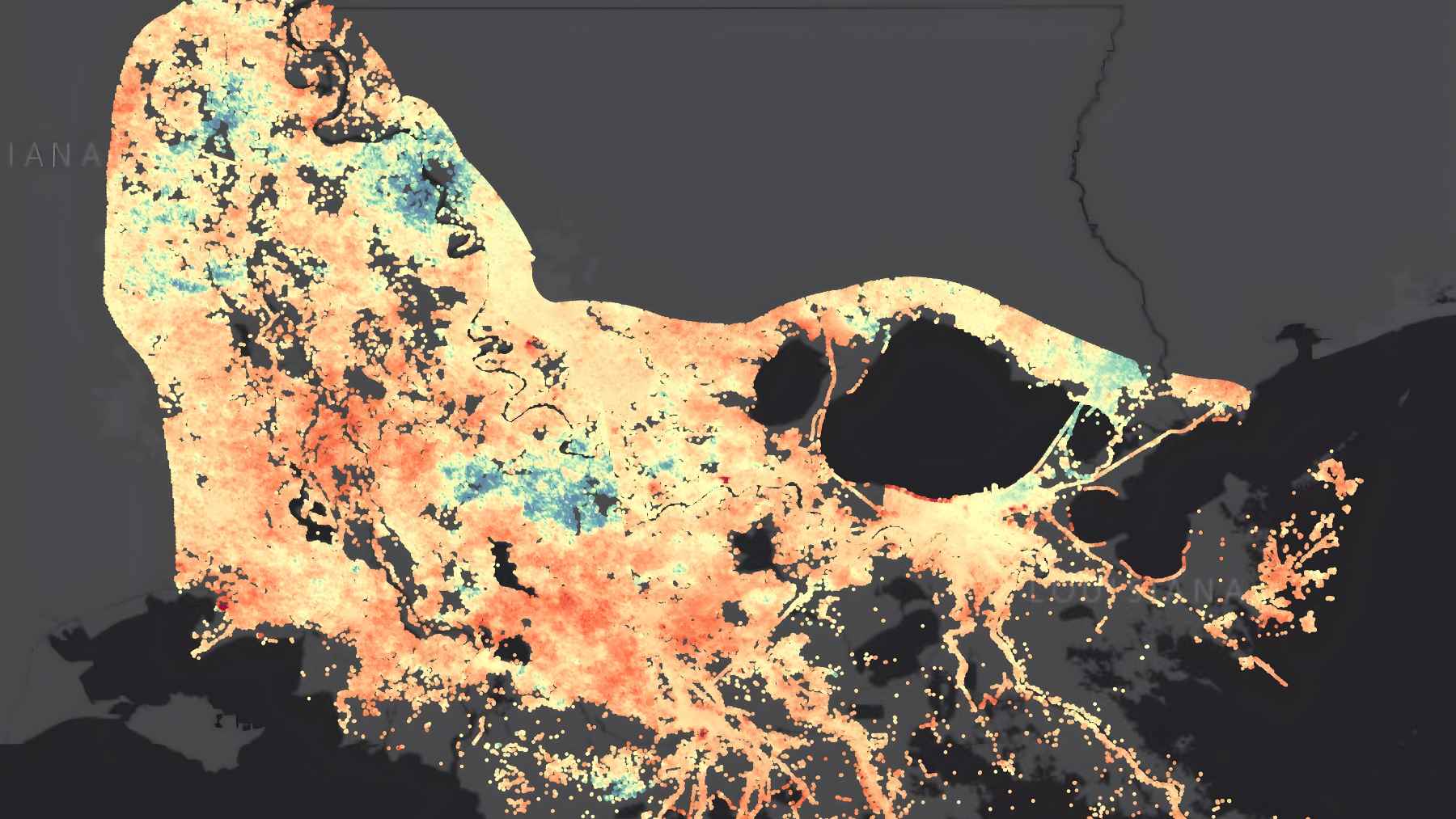

To test whether this balance really happened, the authors compiled every reliable estimate of ancient length of day from Precambrian rocks. Many of the older numbers came from tidal rhythmites and stromatolites, layered deposits that record daily, monthly, and yearly cycles in their fine structure.

More recently, geologists have turned to cyclostratigraphy, which looks for rhythmic patterns in sediments driven by changes in Earth’s orbit and axis, known as Milankovitch cycles.

Two of those cycles, precession and obliquity, depend on how fast our planet spins. Faster rotation means shorter precession cycles. By measuring those cycles in ancient rock layers, researchers can back out how long a day was when the sediments formed. The team gathered 22 such length-of-day estimates from different ages, more than half of which were published in just the last several years.

They then ran a statistical change point analysis on the full dataset. Instead of a smooth curve of steadily lengthening days, the results show a clear plateau. From roughly 2 to 1 billion years ago, Earth’s day length stays nearly flat at about 19 hours, before increasing again toward the 24 hour day we know now.

How could the air above us compete with the pull of the Moon on the oceans?

In the Precambrian, Earth rotated faster, which weakened the lunar tidal torque because friction between oceans and seafloor was smaller. At the same time, the Sun’s heating of water vapor and ozone in the atmosphere drove strong semidiurnal thermal tides. These tides behaved like global pressure waves, sometimes called Lamb waves, that circle the planet.

If the natural period of those atmospheric waves lined up with half of a day, the solar tide would resonate, similar to a playground swing getting just the right push. Under the right mix of temperature and atmospheric composition, that resonance could grow strong enough that the solar tide’s accelerative torque matched the Moon’s braking effect.

The study’s compilation points to a resonance period that would give a day of about 19 hours, slightly shorter than earlier theoretical estimates.

The timing lines up with big shifts in oxygen

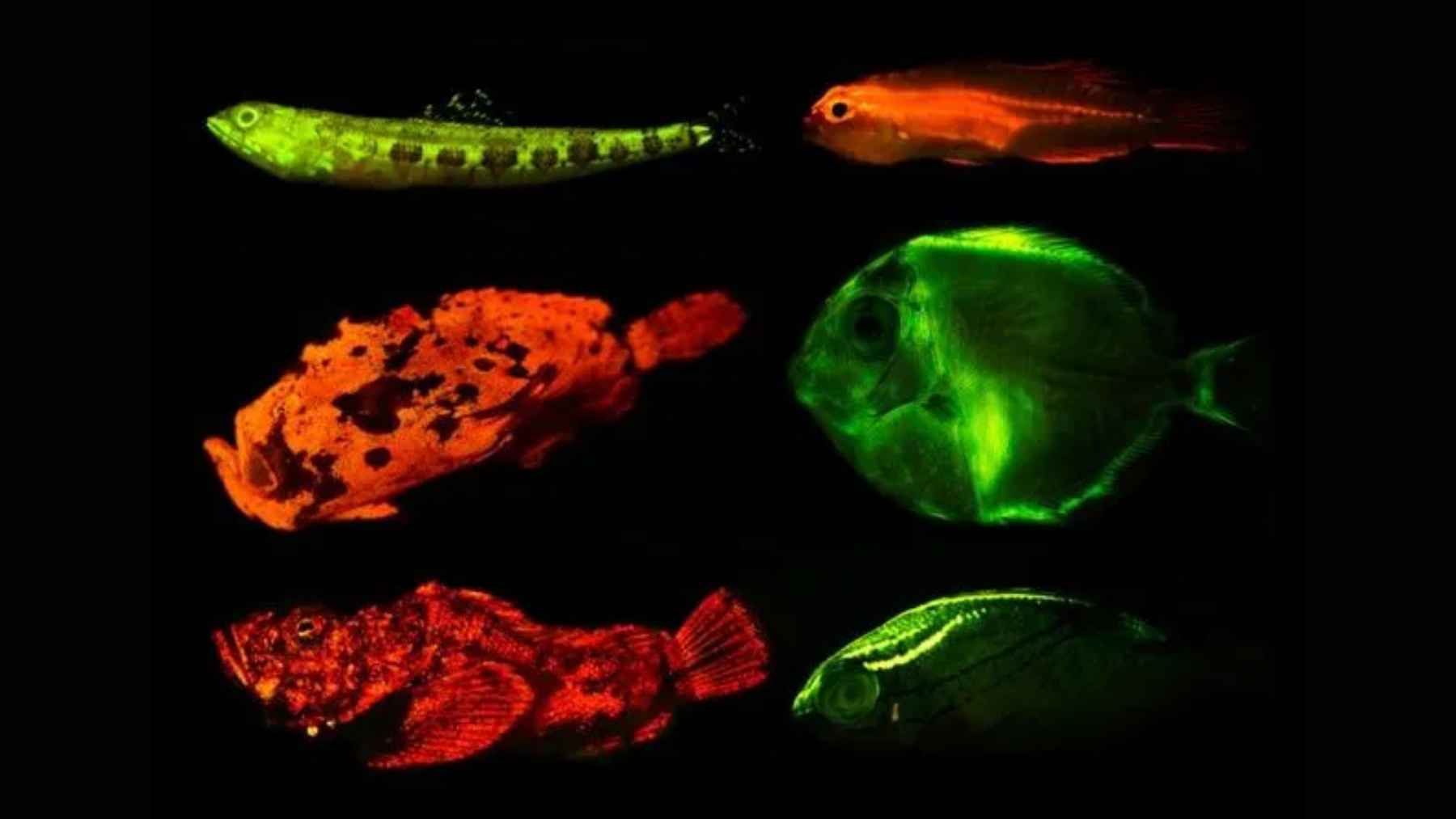

The plateau in day length does not just sit anywhere in Earth history. It overlaps with a long interval of relatively stable climate and slow biological change that scientists call the boring billion. It also falls between two major steps in atmospheric oxygen.

After the Great Oxidation Event, oxygen rose and ozone began to build up in the upper atmosphere. Later, an event sometimes called “Oxit” saw oxygen levels drop again. Changes in oxygen and ozone affect how the atmosphere absorbs sunlight, which in turn influences the strength and speed of thermal tides.

The authors argue that this evolving atmosphere could have nudged Earth into and eventually out of tidal resonance. They also note that longer days after the resonance broke may have given photosynthetic microbes more continuous sunlight, helping them push oxygen to levels that can support large, complex animals. Other researchers have suggested similar links between rotation rate and oxygenation.

From deep time to daily life

For most of us, the length of the day feels fixed. Sunrise, rush hour, kids’ bedtimes, the glow of city lights at night. Yet this study reminds us that day length is a moving target shaped by the interaction of oceans, air, and the Earth-Moon system.

To a large extent, the new results are still a first pass. The mid-Proterozoic plateau rests on a limited set of high quality rock records, and the exact atmospheric conditions that created the resonance remain under active investigation. But the idea that the atmosphere once held Earth’s spin in a billion year stalemate is a powerful one.

In practical terms, it shows that even something as simple as the length of a day can be tied to climate, chemistry, and the slow story of life on our planet.

The study was published on the Nature Geoscience site.