For years, scientists pictured Titan, Saturn’s biggest moon, as a world with a huge hidden ocean tucked under its frozen crust. A new study now suggests something stranger and maybe even more promising for life, with Titan acting more like a frozen sponge filled with thick slush and tunnels of meltwater near its rocky heart.

The research team, led by Flavio Petricca at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, went back to precision gravity data from the long‑running Cassini mission. Using new analysis techniques together with lab work on high‑pressure ice, they found that Titan’s interior behaves less like an open ocean and more like Arctic sea ice or underground aquifers, shot through with watery channels.

A new look inside Saturn’s largest moon

Cassini orbited Saturn for more than a decade, tracking tiny changes in Titan’s gravity as the moon moved closer to and farther from the planet. As Saturn pulls on Titan, the moon slowly stretches and squashes, a process scientists call tidal flexing, similar to squeezing a stress ball in your hand.

Back in 2008, those shape changes were strong enough that researchers proposed a global subsurface ocean to explain how easily Titan’s icy shell seemed to bend. The new work adds an extra piece of information by focusing on timing and shows that Titan’s shape lags about 15 hours behind the peak of Saturn’s pull, a delay that hints at something much thicker and stickier than simple liquid water.

From global ocean to slushy tunnels

The Nature study finds that Titan loses far more tidal energy as internal heat than a world with a smooth underground sea should. In simple terms, Titan behaves less like a calm swimming pool and more like a heavy mix of ice grains and water that resists motion, then slowly relaxes.

Petricca’s team tested many possible interior structures and found that only a thick layer of high‑pressure ice, laced with meltwater pockets, can match Cassini’s gravity data and the observed delay in Titan’s flexing. He described the strong energy loss inside Titan as a kind of “smoking gun” that the interior is very different from earlier models that relied on a simple ocean.

At the University of Washington, Baptiste Journaux and colleagues used their cryo‑physics lab to study how water and ice behave under the crushing pressures expected deep inside Titan. Their experiments show that the moon’s watery layer is so thick that water and ice act differently than in Earth’s oceans, helping explain why a slushy mix fits the data better than a wide open sea.

What this means for the search for life

At first glance, losing a planet‑wide ocean might sound like bad news for anyone hoping Titan hosts alien microbes. Instead, the team argues that networks of “slushy tunnels” and small pockets of freshwater at roughly room temperature could actually offer richer spots for simple life to develop.

In a large ocean, nutrients and energy sources can be spread thin. In Titan’s case, nutrients and organic molecules could collect inside confined meltwater pockets where rocky material, slushy ice, and complex surface chemistry all meet. One of the study’s coauthors, Ula Jones, has noted that this kind of environment may expand the range of places scientists consider habitable, a bit like how hardy organisms thrive inside salty sea ice on Earth.

For people back on Earth, it helps to imagine underground wells and aquifers instead of a single global sea. If Titan really holds countless small reservoirs ofl iquid water, each warmed slightly by tidal heating, the moon might offer many tiny “rooms” where life could get started rather than one giant, uniform habitat. That idea is already nudging researchers to revisit how they search for life on other icy moons in the outer solar system.

Future missions will test Titan’s hidden tunnels

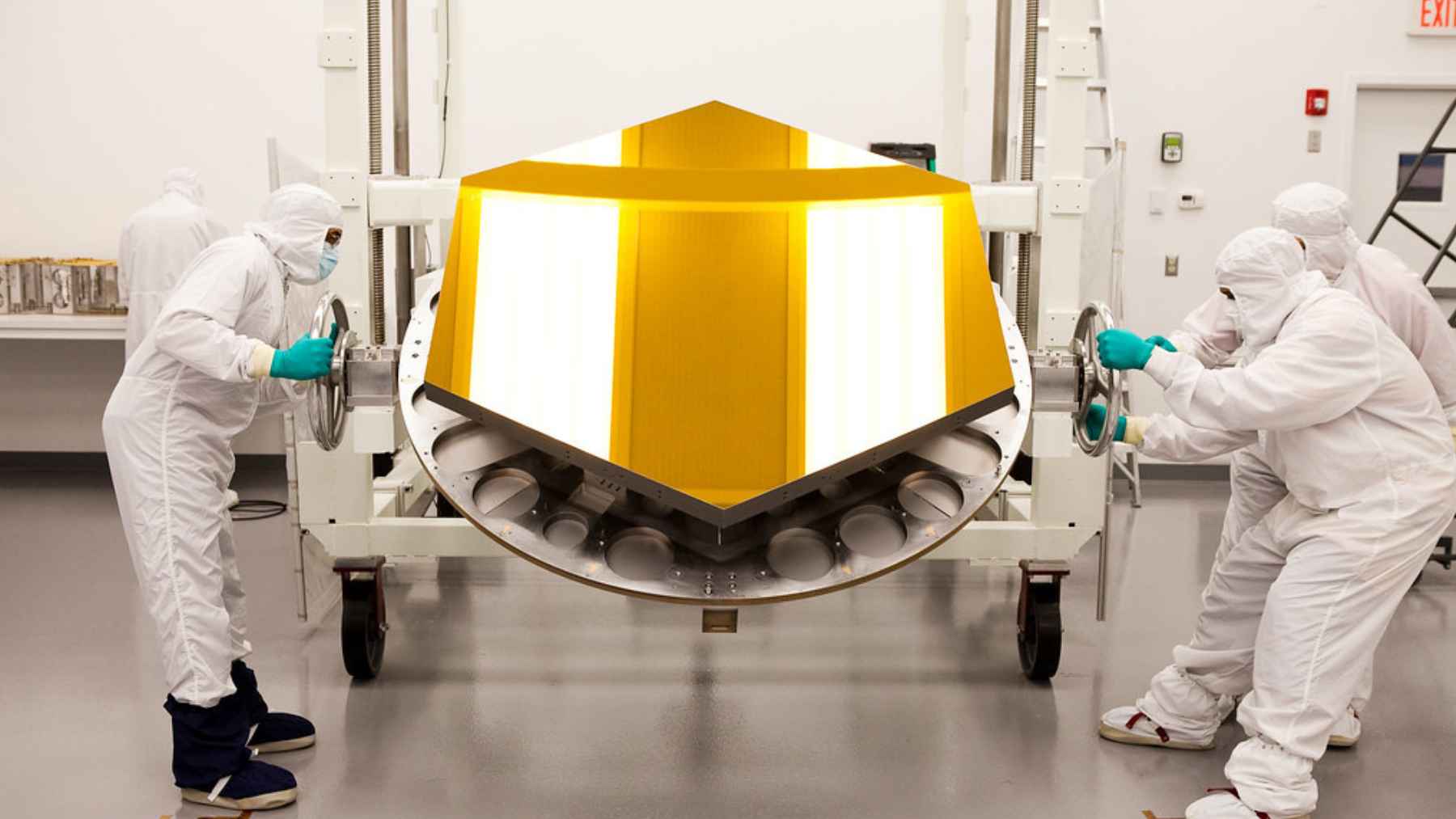

Clues from gravity and radio signals can only take scientists so far, which is why attention is now turning to the Dragonfly mission. This nuclear‑powered rotorcraft is scheduled to launch near 2028 and arrive at Titan in the mid‑2030s, becoming only the second flying vehicle ever operated on another world after the Ingenuity helicopter on Mars.

Dragonfly will hop tens of miles at a time through Titan’s thick, hazy atmosphere, landing on dunes and ancient craters to sample the surface and probe its chemistry. The craft will also carry instruments that can listen for Titan quakes and help reveal how slushy or solid the interior really is, turning today’s models of hidden tunnels into testable ideas.

If those future readings confirm pockets of warm water and rich chemistry below Titan’s crust, scientists may find that one of the most promising places for life in our solar system is not an ocean world at all, but a frozen moon full of slow‑moving slush.

The main study has been published in Nature.

Image credit: NASA