When people imagine first contact with aliens, they often picture giant ships in the sky or wise beings sending peaceful messages. A new scientific idea suggests something very different. According to astrophysicist David Kipping of Columbia University, the first extraterrestrial civilization we detect is most likely to be an extreme, unstable and very “loud” one, possibly caught in a crisis at the end of its history rather than at its calm peak.

Kipping calls this idea the “Eschatian Hypothesis”. The name comes from “eschatos”, a Greek word for “last” or “final”. The basic claim is simple to state, even if the math behind it is more technical. The first alien technosignature we pick up is unlikely to come from a typical, steady society. Instead, it will probably come from a rare civilization that briefly becomes incredibly bright in some way, either by accident or by design.

Astronomical discovery bias in exoplanets and stars

To understand why, Kipping looks back at how astronomy usually works. Our first discoveries are often the oddballs, not the average cases. The very first confirmed exoplanets were found in the early 1990s orbiting pulsars, a type of dead, spinning star that behaves like a cosmic lighthouse. Today we know that exoplanets around pulsars are extremely uncommon, yet they showed up first because the timing signal was so sharp that tiny changes were easy to spot.

Something similar happened with so called hot Jupiters, giant planets hugging very close to their stars. Before the year 2000, a large fraction of known exoplanets fell into this category. Now we know hot Jupiters orbit less than one percent of Sun-like stars. They dominated early discoveries simply because they were easier to detect, not because they were normal.

The night sky teaches the same lesson. Roughly a third of the stars you can see with the naked eye are swollen giant stars, even though only a small fraction of all stars are in that brief, late phase of their lives. Supernovae are another example. A galaxy like the Milky Way only gets about two per century, yet modern surveys see thousands every year because they are so bright.

Technosignatures and planetary crises

Kipping argues that technosignatures from alien civilizations will follow the same pattern. The loudest, strangest cases will stand out first. In his model, he splits civilizations into quiet and loud. Quiet societies radiate at a low, steady level for most of their lifetimes. Loud ones go through a short phase when their output in some detection channel spikes to extreme levels.

He then asks a simple question. If loud phases are rare and short, can they still dominate what we see? The answer is yes, if they are bright enough. Using a toy model, he shows that if a civilization is loud for only one-millionth of its lifetime, then that brief episode needs to be roughly ten thousand times brighter than its quiet state to be more likely to show up in our surveys.

In another example, if every society spends a tiny slice of its history in a loud phase, only about one percent of its total accessible energy budget has to be dumped into that window for such events to dominate detections.

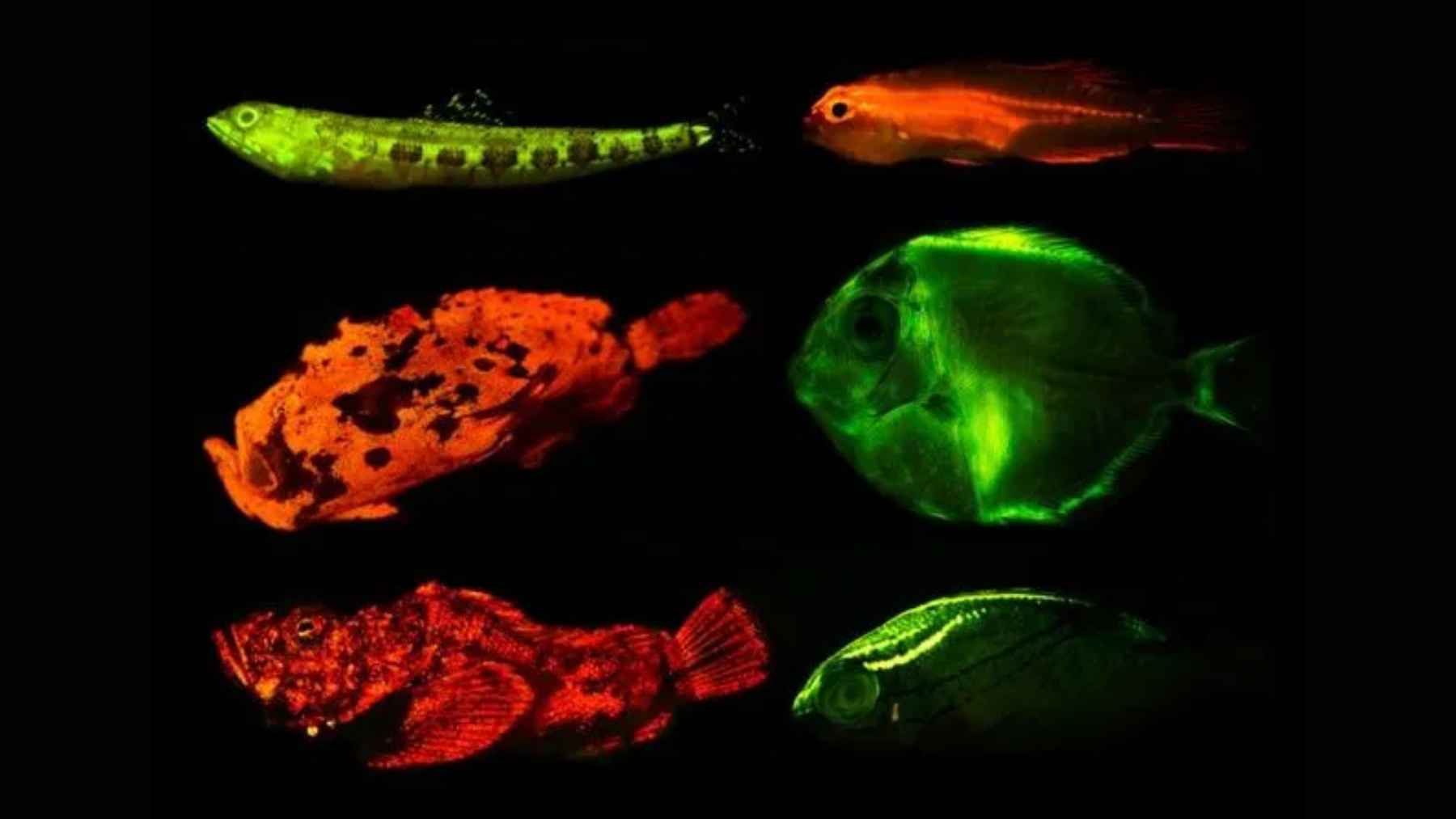

What would make a civilization that loud? Here is where environmental science walks into the story. Kipping points out that technosignatures are, by definition, departures from natural equilibrium.

Other researchers have already suggested that human-driven climate change, ozone destroying chemicals and industrial air pollution could all act as technosignatures on a planetary scale. In other words, a world that is heating rapidly, with carbon levels and complex pollutants climbing in its atmosphere, might look very “loud” to a distant observer.

For our own species, Kipping notes that the brightest flash we could produce with current technology would likely be a global nuclear war, a completely unsustainable burst of energy. That kind of event would clearly be a terminal or near-terminal phase, not business as usual.

On the softer side, a planet wrapped in smog and greenhouse gases is also broadcasting a warning. From far away, it might be easier to notice the chemical scars of an overheating world than the quiet glow of a stable, low-impact society.

Search for extraterrestrial intelligence strategies

The “Eschatian Hypothesis” also changes how scientists think about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Instead of focusing only on narrow, long-term signals such as radio beacons, Kipping argues that we should lean into wide-field, high-cadence surveys that watch the sky continuously. Facilities like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, EvryScope and the Gaia alert stream are turning the sky into a time series, catching brief, odd flashes and unexplained transients.

Kipping suggests that search strategies should become more “agnostic”. In practice, that means looking for strange changes in brightness, spectrum or apparent motion that do not fit any known natural phenomenon, rather than chasing a single, predefined type of alien beacon. Efforts that hunt for anomalies of any kind could be our best route to spotting a civilization in its loud, unstable phase.

Planetary sustainability and our place in the cosmos

For readers used to thinking about energy bills, carbon footprints and planetary limits, the ecological twist is hard to ignore. If Kipping is right, the universe may be filled with mostly quiet worlds where civilizations either stayed sustainable or faded away quietly. The ones we notice first could be the unlucky few that push their planet into a dangerous state and light up the sky as they do it.

That raises an uncomfortable question. If someone out there is watching Earth right now, what kind of civilization do they think we are?

The study was published on the journal site Research Notes of the AAS.