A new line of research says we may not need fantastical warp drives to reach another star within a single lifetime. Instead, we might lean on something we already know how to build in particle accelerators on Earth, then scale it up in space.

A recent study proposes using relativistic electron beams to power a thousand-kilogram probe all the way to Alpha Centauri in roughly forty years, instead of the many tens of thousands that current technology would need.

Why rockets alone are not enough

Even the most advanced chemical rockets burn through their fuel quickly and then spend the rest of the journey coasting. That works for Mars. It does not work for a star more than four light years away.

As engineer Jeff Greason puts it, chemical rockets, even with gravity assists and close flybys of the sun, “just do not have the ability to scale to useful interstellar speeds.”

The distance problem is brutal. Alpha Centauri sits about 4.3 light years from Earth, around two thousand times farther from the sun than Voyager 1 has managed so far. No space agency is likely to fund a mission that needs centuries before it can send back its first data.

Researchers argue that if we want useful science within thirty to fifty years, the spacecraft has to move at a noticeable fraction of light speed.

Beaming power instead of hauling fuel

Greason and physicist Gerrit Bruhaug, working with Tau Zero Foundation and Los Alamos National Laboratory, focus on a class of ideas known as beam riders. In these concepts, the spacecraft does not carry most of its own energy. Instead, power is beamed to it from a distant source.

So far, most beam rider studies have relied on intense laser light. Projects like Breakthrough Starshot imagine gram-scale probes pushed by huge laser arrays for a short burst near Earth, then coasting through the void.

The catch is that laser beams spread out quickly. Practical designs can only push effectively for a tiny slice of the total journey, on the order of a tenth of the distance between Earth and the sun.

What makes electron beams different

The new work takes a different tack. Instead of light, it uses a narrow beam of electrons accelerated to nearly light speed. At those energies, the beam behaves in a surprisingly cooperative way. Normally, identical negative charges repel one another and a long beam would quickly puff out.

At relativistic speeds and in the thin plasma that fills interplanetary and interstellar space, the electrons experience what accelerator physicists call a relativistic pinch. The surrounding plasma helps confine the beam, while time dilation in the electrons own frame leaves them little time to push each other apart.

Calculations in the paper show that a relativistic electron beam could stay tight enough to deliver power over distances of one hundred to one thousand astronomical units, far beyond the effective reach of laser systems. To do that, the transmitter would operate at around gigawatt power levels, with individual electrons carrying roughly 19 billion electron volts of energy.

Unlike a simple light sail, the beam mostly carries energy rather than momentum. The spacecraft would need hardware that grabs that incoming energy and throws out a working fluid as exhaust, turning the beam into thrust.

Greason notes that this converter has to be incredibly efficient, since any wasted energy ends up as heat that could literally melt the vehicle

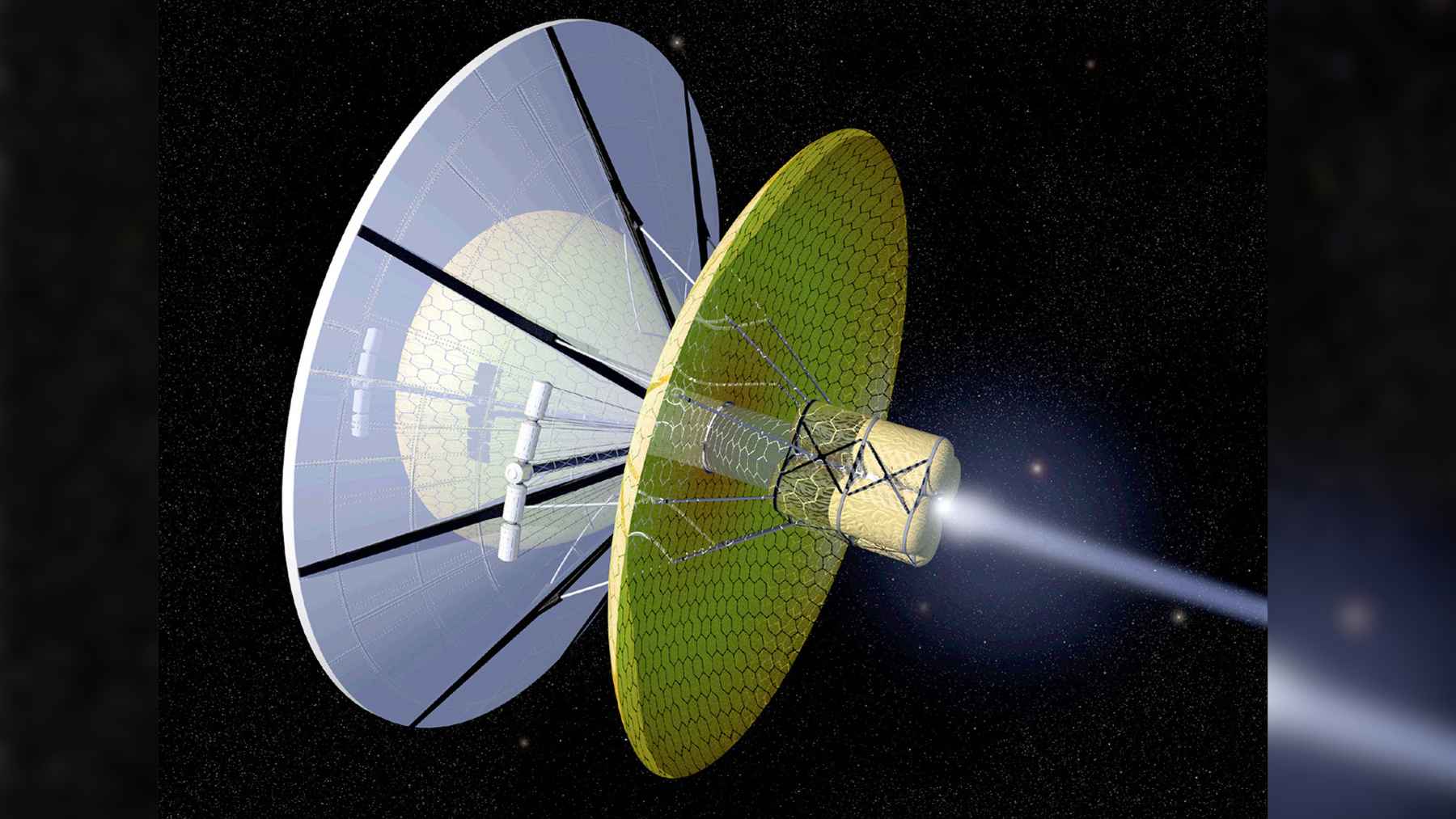

Solar statites as off-world power plants

To feed such a powerful beam, the team proposes a special kind of spacecraft called a statite, hovering close to the sun. A statite balances solar gravity with the pressure of sunlight and magnetic forces, letting it hold a nearly fixed position instead of circling the star.

Park it near the orbit reached by the Parker Solar Probe and it can soak up intense sunlight, convert it to electricity, and drive the electron accelerator, all while hiding delicate equipment behind a thick sunshield.

Because the statite does not whip around the sun in a tight orbit, it can keep the probe in its sights for weeks or months. That long push is key. The study finds that a thousand-kilogram probe, roughly in the class of Voyager but with far more modern electronics, could slowly build up speed until it reaches about ten percent of light speed. At that pace, the trip to Alpha Centauri would take about forty years instead of the roughly seventy thousand years a Voyager style craft would need.

Many open questions

This all sounds neat on paper. The authors are the first to say that it is not ready to fly. Beam stability in the real solar magnetic environment is still poorly understood, especially the way the beam will interact with the return electric current that must flow through the surrounding plasma.

High-fidelity computer simulations and experiments in space will be needed to test whether such beams really stay on target across hundreds of astronomical units.

Even if the beam behaves, engineers must invent compact beam receivers that channel huge power flows into thrust without adding too much mass or cooking the spacecraft.

Greason suggests that a smaller-scale experiment, where a satellite sends an electron beam toward the moon, could be one way to check the models before anyone dares to aim for another star.

Why it matters here and now

For most of us stuck in traffic under a hazy sky, starflight feels remote. Yet the same tools needed to beam power across deep space could, in the long run, reshape how we move and power craft inside our own solar system.

The authors note that relativistic beams and statites might first be used for very fast trips to outer planet destinations or as long-distance space-based power lines for infrastructure around Earth and the moon.

If those precursor missions ever happen, they could squeeze more science out of each launch and open the door to cleaner, more efficient space operations. The road to another star would then start with better tools for exploring our own backyard.

The study was published in Acta Astronautica.