It was supposed to be a straightforward farm project. Dig a five-acre lake, raise tiger bass, manage oxygen and water quality, and harvest fish. Nothing more dramatic than that.

Instead, in less than three years, a former peanut field turned into a living sanctuary crowded with bald eagles, deer, owls, ducks, squirrels, raccoons, and hungry predators above and below the surface.

What began as aquaculture quietly became a full-scale ecosystem, a natural experiment in what happens when you add water, food, and structure to empty land and simply let life decide.

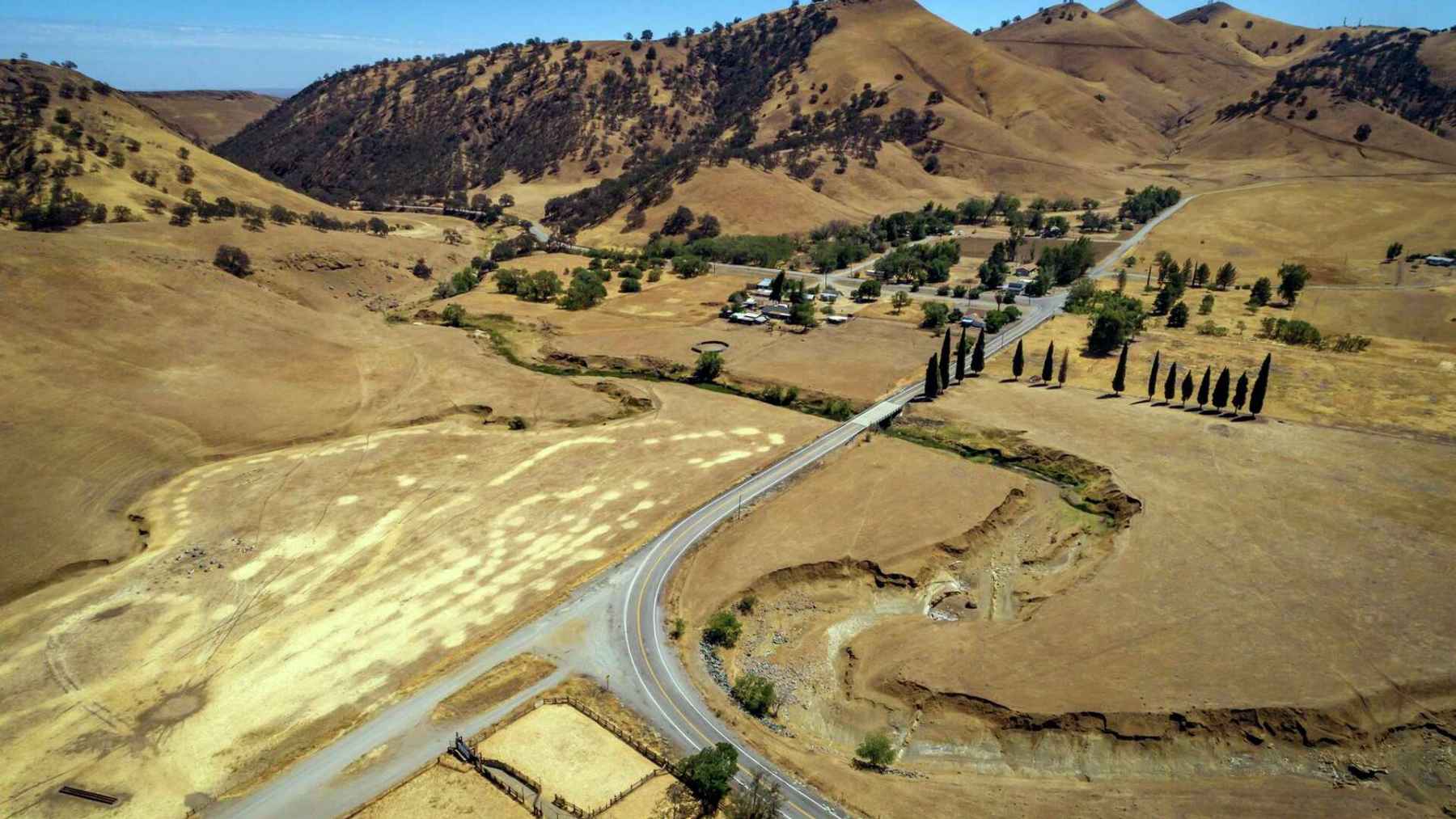

From peanut field to experimental lake

The story starts with a bare, worked-over field planted with peanuts. The landowners decided to carve out a five acre lake and treat it like a technical project, carefully managing oxygen levels, underwater structure, and water quality so the fish would grow fast and stay healthy.

At first, the lake was a closed system, almost clinical in its design. It held water and fish, nothing more. Then, within about six months, the silence around it began to change. Wings passed overhead, tracks appeared in the mud, and shadows started returning at the same hours every day.

A fish farm that turned into an ecosystem

The early focus was all on tiger bass. Submerged structures were placed to give them ambush spots. Monitoring was constant, with adjustments to feeding and aeration. Everything pointed toward a neat, predictable fish farm with clear numbers and stable output.

But animals kept coming back. The same visitors showed up again and again, turning random sightings into routines. The lake stopped behaving like a piece of equipment and started acting like a biological magnet, pulling energy and attention into the surrounding land as much as into the water.

When bald eagles and deer choose to stay

The turning point came when a bald eagle dropped down to drink from the new lake instead of flying past. Before, these birds crossed the property without stopping. Now they had a reason to land. The introduction of tilapia and trout created an easy, concentrated food source that was hard to ignore.

In response, the humans built a tower, then a platform, and eventually a nesting spot. The eagles brought in their own nesting material and adjusted it for wind and weather. It was not a formal reintroduction with cages and release schedules. It worked more like an invitation that wild birds chose to accept.

Ducks, owls, and the daily risk

Deer also began to linger. They did not just drink and flee. They lay down near the water and started to ignore nearby people, a strong sign that they viewed the place as safe, predictable, and rich in resources. In practical terms, that meant shade, water, and steady food.

Ducks followed. Whistling ducks, dabblers, and divers all used the lake, and one resident pair raised ten ducklings. Predators came too, including owls that hunted over the water. Not every scene had a happy ending. A sociable duck nicknamed Romeo tried to befriend every newcomer, living proof that staying in a wild sanctuary still involves constant risk.

Squirrels, raccoons, and the night shift

Once food and cover appeared on the banks, smaller mammals moved in. A fox squirrel started collecting peanuts. A small house on the property became a focal point. First one animal used it, then another, and soon a rat and a raccoon also claimed the space.

Daytime and nighttime occupancy split, with one occupant by day and another by night. At one point, an animal chewed through a window frame to create its own emergency exit. It might sound like a cute story, but it is really a snapshot of raw competition around a new resource. The lake sat at the center, and everything else orbited around it.

Underwater life writes its own rules

Below the surface, cameras captured a different kind of drama. Large female bass staged ambushes, striking with impressive efficiency. Some of these fish ate two or three prey items a day, turning that steady intake of protein into rapid weight gain.

Giant freshwater shrimp patrolled the bottom, while dragonflies skimmed the surface and sometimes became fish food.

Tilapia guarded their young by holding them in their mouths, a behavior known as mouth brooding, while other fish hunted around them. In roughly three years, a few bass grew from about two pounds to seven pounds. The entire food chain became visible in real time, from insects and shrimp up to powerful top predators.

An open air laboratory in only 1,000 days

Today the site operates less like a closed fish farm and more like an open-air laboratory. Cameras watch both shore and water. There are plans to stream live video. Feeders can be triggered remotely. Some fish even carry tags so they can be recaptured, measured, and logged, turning casual fishing trips into data collection.

What started as a technical aquaculture project has become a continuous observation of an emerging ecosystem. It raises a simple but challenging question. How many potential sanctuaries are we overlooking just because no one is willing to change something as basic as where the water goes.

The main work has been documented by the creators of the lake project in their own ongoing reports and video materials.

The official fact sheet about how small farm lakes can support wildlife was published by the U.S. Geological Survey in its report Farm Ponds Work for Wildlife.