Astronomers have caught a baby star in the middle of a cosmic backfire. A high-speed jet shot out from the young star WSB 52, inflated a giant bubble of gas, and that bubble then slammed straight into the star’s own planet-forming disk, warping it and blowing material away. The finding suggests that the birthplaces of planets can be far more violent than scientists had assumed until now.

WSB 52 and its protoplanetary disk

WSB 52 sits about 440 light years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Ophiuchus. It is a young, Sun-like star surrounded by a flat, rotating disk of gas and dust where future planets may take shape. The team did not point a new telescope at it.

Instead, they went back to archived data from the Atacama Large Millimeter or submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile and reprocessed the observations with fresh eyes and updated tools.

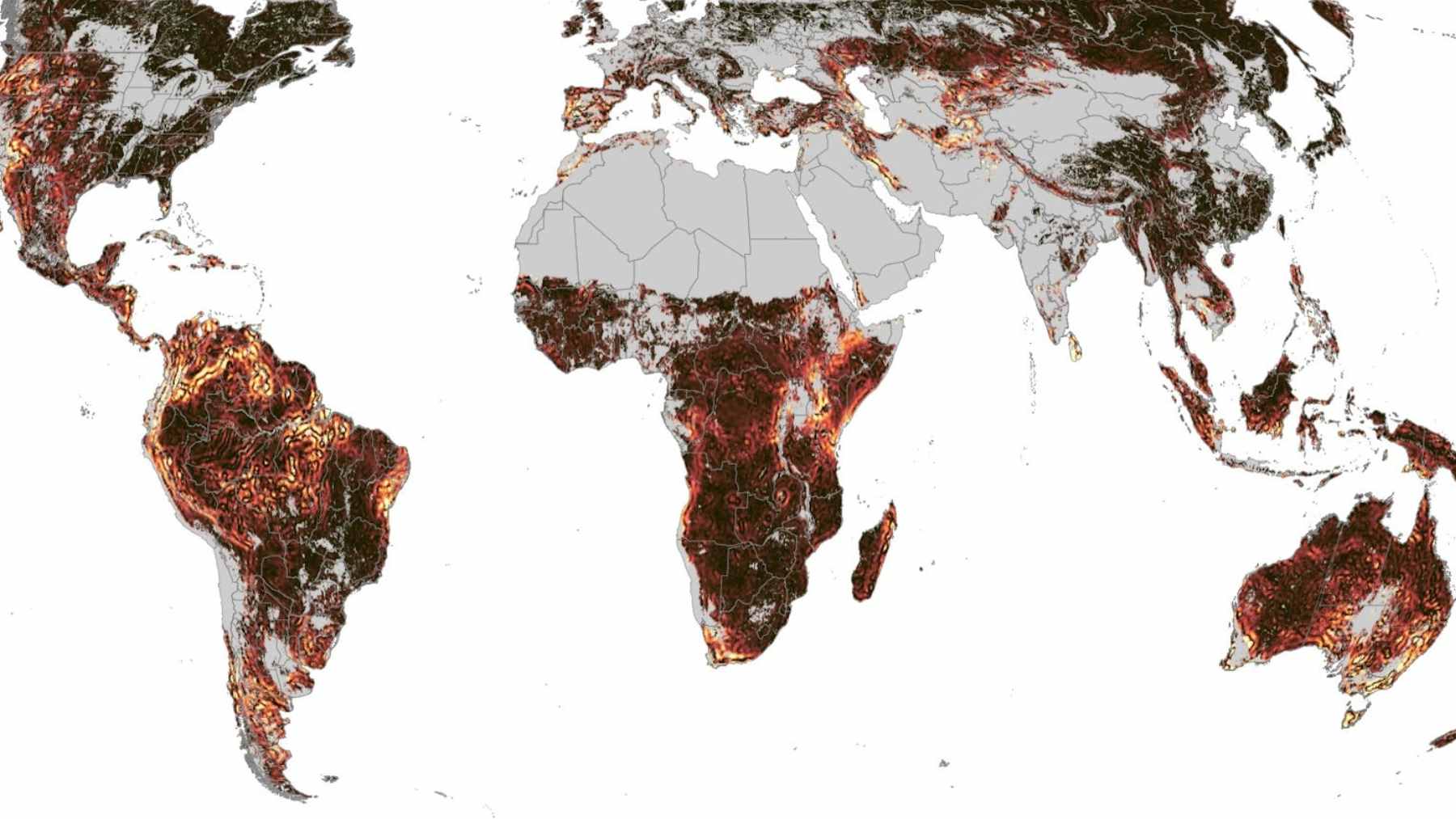

ALMA data reveals an expanding bubble and shock wave

What they saw looked a bit like a sci-fi scene. Using radio maps of carbon monoxide gas, the astronomers picked out a bubble of material expanding uniformly away from the star, almost as if someone had taken a three-dimensional medical scan of the system. At the edge of that bubble sits a shock front where fast moving gas crashes into slower gas.

Right where that front meets the disk, the disk is bent out of shape, and part of its gas appears to be streaming away fast enough to escape the star’s gravity.

Evidence a stellar jet can reshape a planet forming disk

The geometry is the real smoking gun. The center of the bubble lines up neatly with the rotation axis of the disk, and the energy stored in the moving gas is on the order of 10⁴¹ ergs. That alignment is extremely unlikely to happen by chance, so the team concludes that a narrow, fast jet from WSB 52, launched a few hundred years ago, rammed into colder gas near the disk, compressed it, and triggered an explosive expansion that created the bubble.

This is the first clear evidence that such jets can feed back directly onto the planet-forming disk itself rather than only stirring the wider cloud around a star.

What the discovery means for planet formation and the Solar System

In more everyday terms, imagine aiming a high-pressure hose at a wall and getting splashed by your own water. Something similar is happening on a far grander scale around WSB 52. Co author Masataka Aizawa notes that scenes in science fiction where a beam hits a target and debris flies back toward the source are not that far off from what nature is doing here.

He also reflects that “nature is far more complex than humans think,” a reminder that even well studied processes like star formation still hold surprises.

Why should anyone who is more worried about climate change or the electric bill care about a baby star hundreds of light years away? Because every rocky world, including Earth, was once part of a disk like this. If explosive bubbles driven by stellar jets are common, they could tilt disks, strip material, or shove gas and dust into new orbits.

Over millions of years, those nudges may influence where planets end up, how massive they become, and even how much water or carbon-rich material they can hold at their surfaces.

For our own Solar System, that kind of feedback might have helped decide which parts of the young disk stayed calm enough to build Earth and which zones were too turbulent. It adds one more layer to the story of how a planet with oceans, forests, and traffic jams could emerge from a cold, dusty ring around a newborn star.

The calm blue sky we look at today may be the long term result of many such violent episodes settling down.

Why this matters for future astronomy research

The discovery also gives astronomers a new way to test planet formation theories in practice. If jets can punch bubbles that hit disks, other young stars should show similar scars in high-resolution radio maps. ALMA’s sensitivity to faint molecular gas makes it a key tool for hunting these structures, and future observatories will likely join in, checking how often disks are caught in the blast.

The work is still at an early stage, and the researchers themselves stress that the exact origin of the bubble needs more study. For the most part though, specialists agree that the jet bubble disk interaction seen in WSB 52 opens an important new window on how stars and planets grow together.

The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), M. Aizawa et al.