Deep beneath our feet, the planet has been quietly making hydrogen for billions of years. A new scientific review suggests that Earth’s crust has generated enough hydrogen energy over geologic time to match about 170,000 years of today’s global oil use. For anyone watching the climate crisis and the monthly energy bill, that number jumps off the page.

The reality is more complicated. Much of that gas has probably reacted away or leaked to the surface, and scientists do not yet know how much remains stored in drillable reservoirs. In their review in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, researchers from the University of Oxford, Durham University, and the University of Toronto map out where natural hydrogen is likely to form, migrate, and get trapped in the continental crust.

Why does this matter? Hydrogen already underpins fertilizer production, oil refining, and a growing list of heavy industries. Yet almost all of it is currently made from coal or natural gas, a route that produces an estimated 2.4 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. With demand expected to multiply by mid century, cleaning up hydrogen supply is central to most net zero plans.

A hydrogen factory in the rocks

The new study explains how the planet makes its own hydrogen without human help. One key process involves water reacting with iron-rich rocks such as peridotite in a reaction that converts iron to a more oxidized form and releases hydrogen gas. Another relies on natural radioactivity from elements like uranium, thorium, and potassium, which splits water molecules in tiny pores and fractures, also freeing hydrogen.

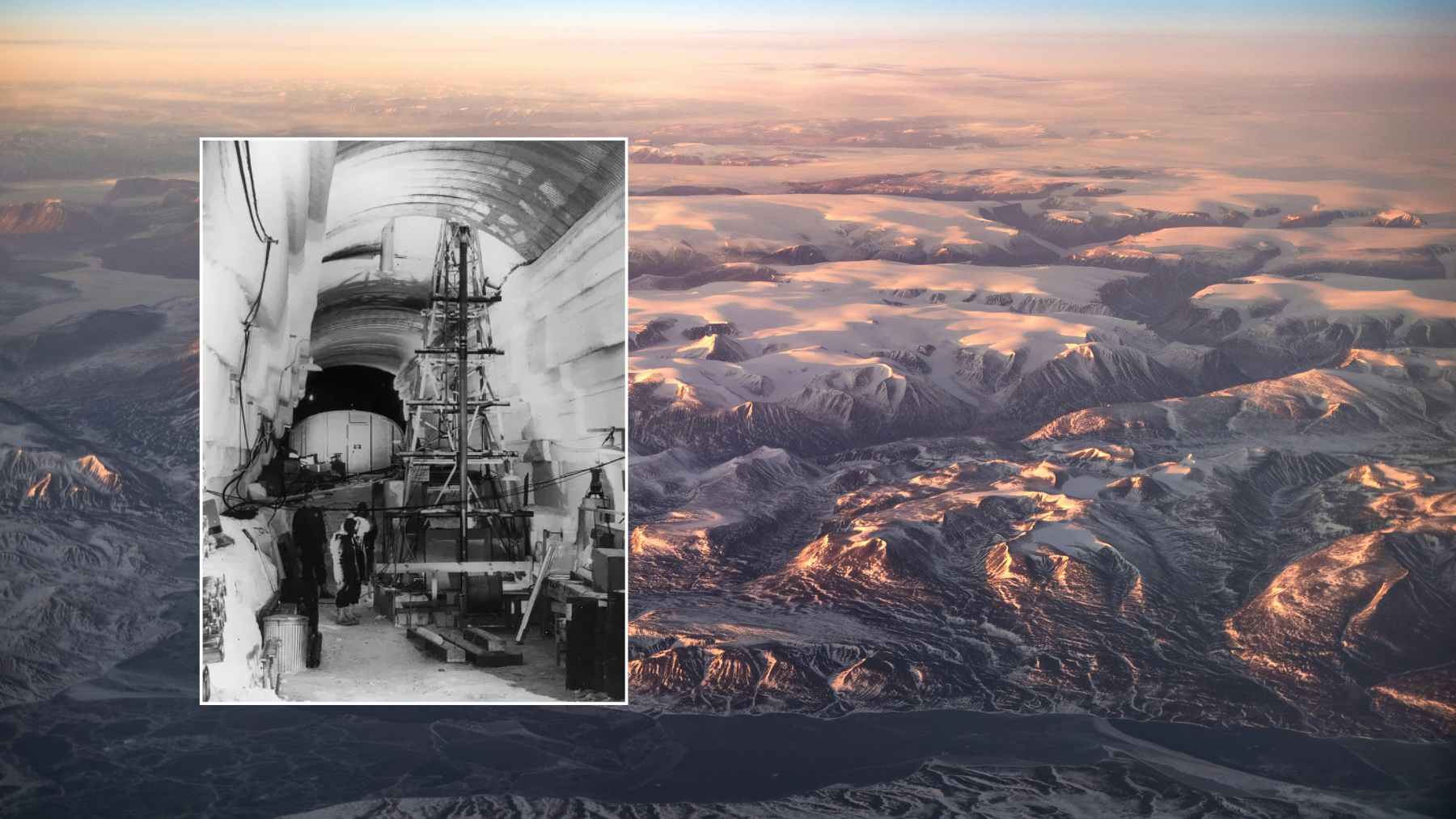

These reactions run slowly but relentlessly, over thousands to hundreds of millions of years. In the right settings, the hydrogen can build up, move through fractures, and collect in porous rocks sealed beneath layers of shale, salt, or other tight rock. At Bourakebougou in Mali, for example, high-purity natural hydrogen discovered during a water well project now powers a village-scale electricity system with very low direct emissions.

Solving the underground puzzle

Ballentine and his co-authors argue that finding these accumulations is no longer a shot in the dark. Their work pulls together what is known about four steps in a hydrogen system: generation, transport, trapping, and preservation, and turns it into an exploration recipe that can guide drilling. You need the right source rocks, enough water, open pathways such as fractures, and a robust seal to keep a gas phase from escaping.

Preservation may be the hardest part. Study co-author Barbara Sherwood Lollar notes that “underground microbes readily feast on hydrogen” wherever they can reach it, stripping away the gas that drillers might hope to find. Chris Ballentine likens the search to “cooking a soufflé” where getting one ingredient, temperature, or timing wrong means disappointment for explorers and investors.

The review highlights several geological environments that stack the odds in our favor, including belts of ancient ocean crust called ophiolites, very old Archean greenstone belts, large igneous provinces created by massive eruptions, and alkaline granite regions.

Many of these occur on every inhabited continent, which is why advocates see natural hydrogen as a truly global opportunity rather than a niche resource.

Promise and limits for the energy transition

On paper, the climate benefits look significant. Modeling suggests that producing hydrogen from these underground accumulations could carry a far lower greenhouse gas footprint than today’s fossil-based hydrogen, especially if co-produced gases are carefully handled and leaks are minimized. It would also reduce the need for the huge amounts of electricity and clean water required for making hydrogen by electrolysis.

At the same time, the authors are explicit that this is not a limitless green fountain. The geological processes that create hydrogen work on very long timescales. Continental crust does not refill gas reservoirs on the human timescales of decades or centuries, so natural hydrogen should not be labeled a renewable resource. Nor is it clear how many large, high purity accumulations exist or how fast they would decline once production began.

There are social and environmental questions too. Scaling up natural hydrogen would mean more drilling, seismic surveys, and pipelines, often in rural regions that have already seen oil and gas booms and busts. If governments choose to back this option, strong safeguards, transparent regulation, and fair sharing of benefits will be essential so that local communities are not left shouldering the risks.

For now, the work by Ballentine and colleagues takes the conversation beyond headlines about a hidden jackpot. It offers a clearer picture of what natural hydrogen can realistically deliver, where it might be found, and how much uncertainty still surrounds this new frontier. The next wave of carefully-monitored pilot projects will show whether this quiet gas in the crust can truly help cut emissions or whether it remains mostly out of reach.

The study was published in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

Image credit: Hydroma