If you could rewind the universe to its first billion years and freeze the frame, what would the very first galaxies look like? A new discovery suggests they were anything but simple and smooth.

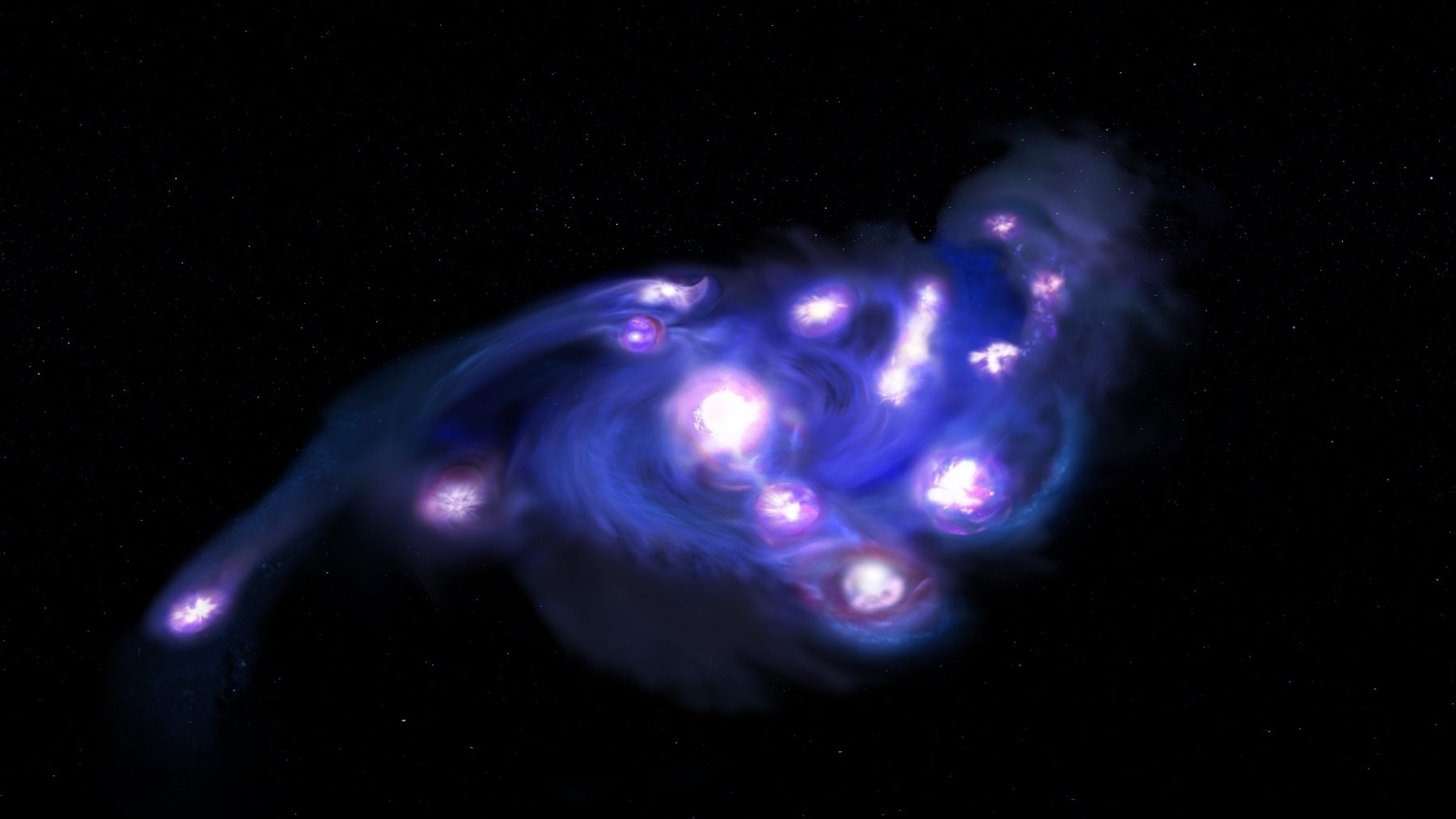

Cosmic Grapes galaxy in the early universe

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Atacama Large Millimeter or submillimeter Array (ALMA) have found a young rotating galaxy, nicknamed “the Cosmic Grapes,” that lived only about 900 million years after the Big Bang.

Instead of a gentle disk of stars, it is packed with at least 15 dense, bright star-forming clumps that bunch together like a cluster of fruit. That crowded structure goes beyond what leading computer models said should be possible in a single early galaxy.

Gravitational lensing and cosmic magnification

The team could see this surprising level of detail only because nature helped. A massive foreground cluster of galaxies bends space around it and acts as a kind of cosmic magnifying glass. This effect, called gravitational lensing, stretches and brightens the light from the distant system so that ALMA and JWST can zoom in far beyond their usual limits.

One of the study’s authors describes the galaxy as “one of the most strongly gravitationally-lensed distant galaxies ever discovered,” which turned it into a rare laboratory for testing theories of how galaxies grow.

Star forming clumps in a young rotating galaxy

More than one hundred hours of observing time went into this single object. With that patience, astronomers were able to map both the cold gas that fuels star formation and the young stars themselves.

They found a rotating disk that looks, in broad strokes, like a normal star forming galaxy. Yet inside that disk sit compact clumps only a few tens of light years across, each with very high gas density. According to the researchers, “these clumps are massive and have high gas densities, conditions that are conducive to forming stars very efficiently.”

In everyday terms, it is a little like flying over a city at night and realizing that most of the light comes from a handful of intensely lit neighborhoods instead of being spread evenly across town. In the Cosmic Grapes, several small regions dominate the glow of young stars. That pattern hints that early galaxies may have grown through many compact bursts of star formation rather than through a single smooth wave.

Early universe simulations and clumpy galaxy disks

What really puzzles theorists is the number of clumps. State-of-the-art simulations of the young universe do produce unstable disks that fragment into a few dense knots. They do not usually produce a rotating system that holds more than a dozen such clumps at once, especially at such an early cosmic time.

The new observations suggest that key ingredients in these models, such as how exploding stars stir and heat gas or how fast material can cool and collapse again, may need to be revisited. As the ALMA team notes, this galaxy “raises key questions about how galaxies form and evolve” in the first billion years.

Another important detail is that the Cosmic Grapes does not appear to be a cosmic oddball. Its mass, size, chemical makeup and rate of star formation place it on what astronomers call the “main sequence” of star forming galaxies.

In other words, it looks fairly typical for its age. If that is right, then many distant galaxies that appear smooth in current images may actually hide similar bunches of clumps that our telescopes simply cannot resolve without help from gravitational lensing.

James Webb Space Telescope and galaxy evolution

This is where JWST really earns its keep. The telescope has already revealed unexpectedly massive and mature galaxies at early times, along with record breaking black holes and odd “little red dot” systems that challenge long-held ideas about how fast structure can grow.

The Cosmic Grapes now add another twist by showing that even apparently ordinary young galaxies can have very complex interiors. Together, these findings hint that the early cosmic “ecosystem” may have been more turbulent and more efficient at building stars than astronomers thought a decade ago.

For readers on Earth who are more used to thinking about energy bills or traffic jams than about galaxy disks, the stakes might feel remote. Yet our own Milky Way almost certainly went through a similar chaotic youth. Understanding how clumpy disks like the Cosmic Grapes settle down over time helps scientists trace how chemical elements for rocky planets and, eventually, life itself were first mixed and spread.

The team behind this work sees their result as a starting point rather than a final answer. Future surveys will search for more strongly-lensed baby galaxies and test whether clumpy structures like this were common or rare.

If many more examples turn up, theorists will need to tune their simulations until they can grow entire virtual vineyards of galaxies that look like the real thing. Until then, the Cosmic Grapes will remain a vivid reminder that the universe still keeps some of its most important details tucked away in tiny bright knots, waiting for the right tools to bring them into focus.

The scientific study was published in Nature Astronomy.

Image credit: : NSF/AUI/NSF NRAO/B. Saxton