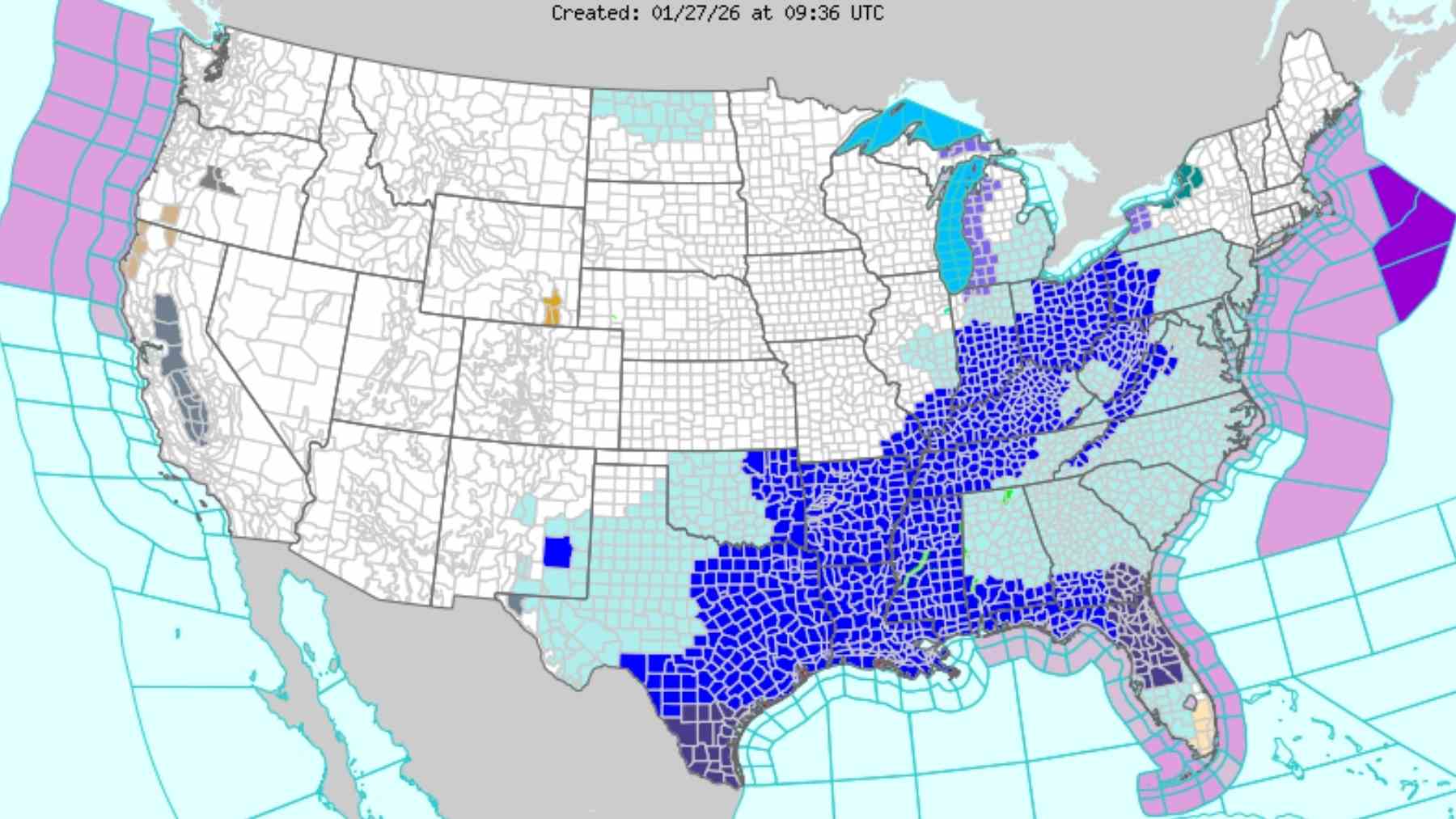

After a stretch of short sleeves and muggy afternoons, much of Louisiana is waking up to something very different: cold, dry air and a run of near-freezing nights. Forecasts from the National Weather Service call for daytime highs in the 50s and low 60s, with light freezes likely north of the I 10 and I 12 corridor and temperatures near the freezing mark in other parts of the state.

A long stretch of pipe‑bursting hard freeze is not expected, but officials are urging residents to protect people, pets, pipes and plants while the chill hangs around.

The timing feels odd because winters along the Gulf Coast have been shifting. Climate assessments show that since about 1970, some parts of Louisiana have lost between 10 and 20 freezing days each year, while hot days and warm nights have become more common.

So when a solid cold front finally arrives, it meets a landscape and a way of life that now expect gentle winters for the most part. Pipes are often uninsulated, power demand jumps as electric heaters kick on and those hibiscus‑lined porches suddenly look very exposed.

Plants, pets and the four P words

State and local agencies are treating this week’s chill as a reminder rather than a crisis. In a January 2024 press release, the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry urged residents to look after animals and vegetation as temperatures dip near or below freezing. Commissioner Mike Strain summed it up by saying that “when we see temperatures start to dip below freezing, it is important to take precautionary measures.”

The guidance is simple: bring companion animals indoors or give them dry shelter, check water so it does not ice over and cover or mulch sensitive plants before the coldest nights arrive. Ecologists note that many native trees, grasses and reptiles have survived swings between warm winters and sharp cold spells, and short freezes are unlikely to wipe them out.

Recent reporting on this winter’s southern cold snap also suggests that most native plants and animals can cope with brief intense freezes, even when snow appears in places that rarely see it. The bigger risks fall on tropical ornamentals, invasive species, early-budding plants and domesticated animals that depend on human care, which is why officials keep repeating that easy to remember list: protect people, pets, pipes and plants.

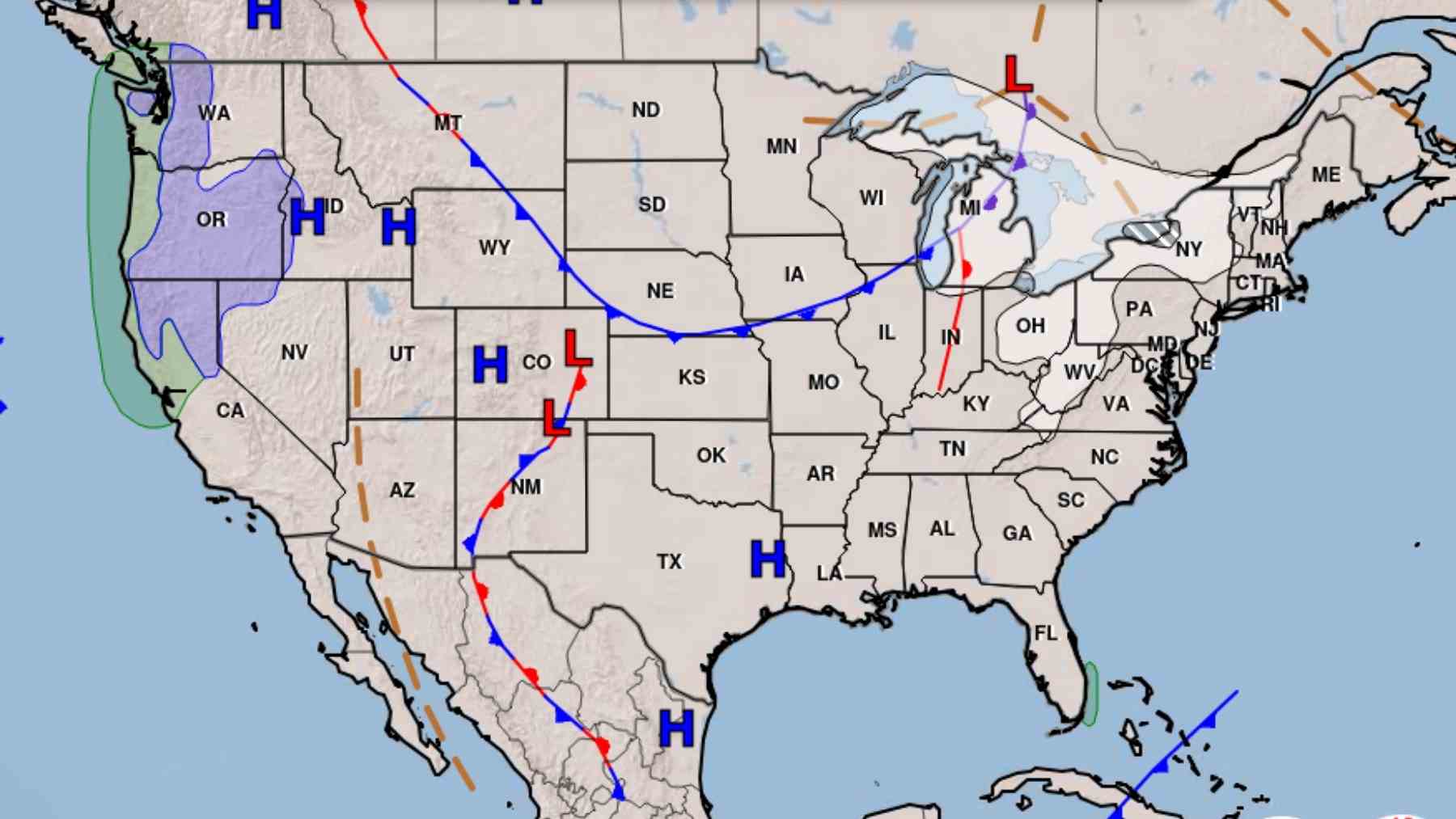

Cold snaps and the polar vortex

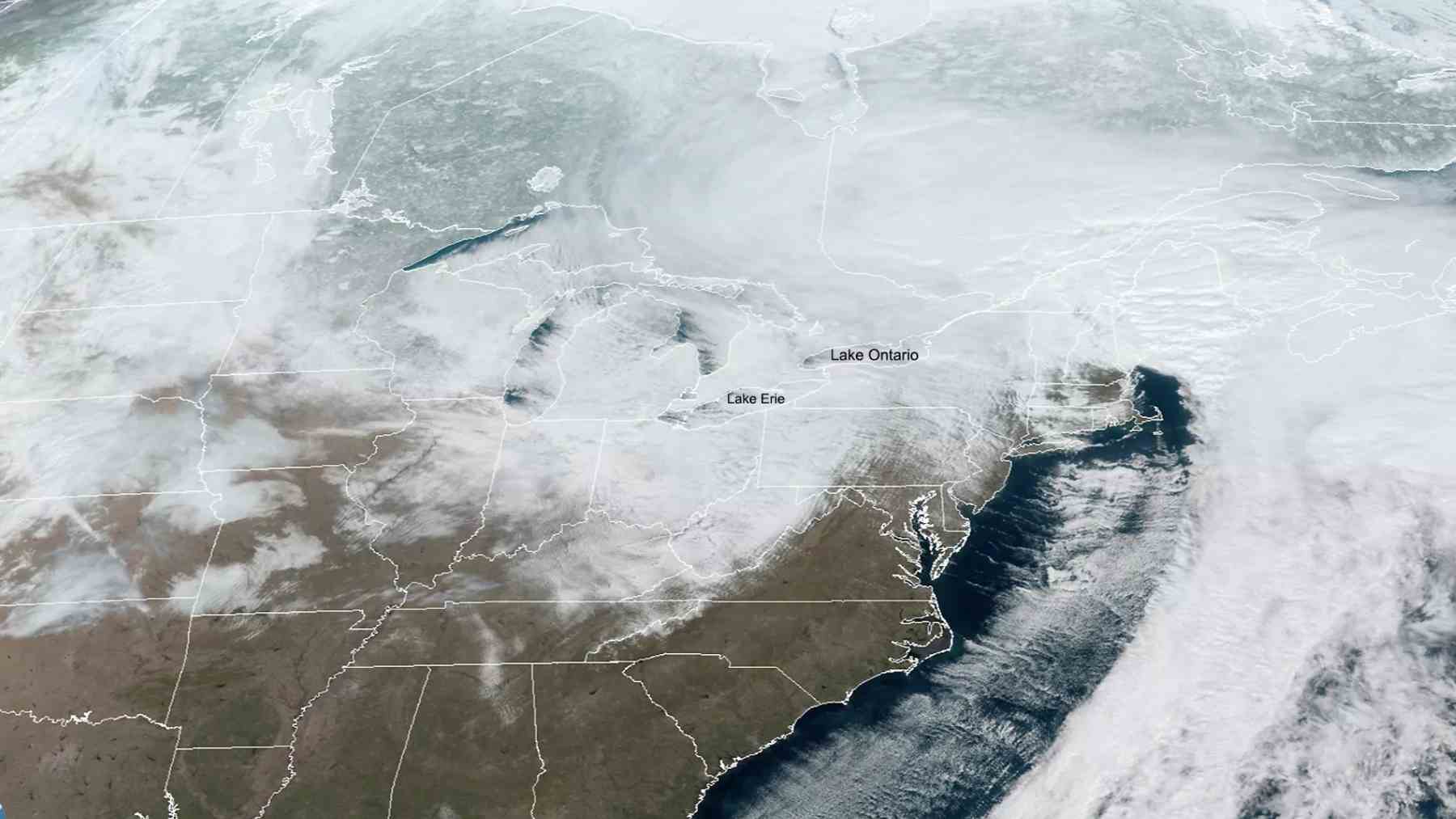

If Louisiana is warming overall, why are residents still scraping frost off windshields and worrying about frozen pipes? The answer sits high above the state in fast-moving rivers of air around the Arctic. Scientists describe how the polar jet stream and the polar vortex act like atmospheric fences that usually keep the coldest air near the pole. As the Arctic warms faster than the mid latitudes, those fences can weaken and wobble, allowing tongues of frigid air to spill south toward places like the Gulf Coast.

A recent study in the journal Science Advances looked at decades of data on extreme cold in the continental United States and found that severe winter outbreaks continue even as average winters warm. The authors linked many of these events to patterns in the stratospheric polar vortex that encourage cold air to surge southward for several days at a time. In practical terms, that means a state that is losing freezing nights on average can still be hit by the kind of cold snap now moving through Louisiana.

Preparing for the next weather flip

For Louisiana, this mix of long-term warming and occasional sharp freezes creates a new kind of climate homework. Households can add simple insulation around outdoor pipes, keep a few plant covers handy and plan gardens around a blend of hardy natives and more delicate species.

Climate and agriculture experts in the state already encourage producers to be flexible and to adapt to growing year‑to‑year variability, rather than counting on the “average” season that used to be more reliable. Local governments are refining freeze plans and communication so people know when to act before temperatures drop.

At the end of the day, this latest cold spell is a reminder that climate change is not only about record heat and sticky summer nights, it also reshapes the odds of when and how winter shows up. Treating freezes as part of a wider story of resilience, from backyard pipes to bayou forests, helps Louisiana prepare for whatever the next flip in the weather brings.

The study was published in Science Advances.