If you have ever looked up at the night sky and wondered when Earth first began to take shape, a new set of images from the ALMA telescope brings that moment a little closer.

A team led by Ayumu Shoshi of Kyushu University reanalyzed public data from ALMA and found clear signs of planet formation in dozens of disks of gas and dust around very young stars in the constellation Ophiuchus.

The work suggests planets can start to grow only a few hundred thousand years after a star is born, not millions of years later as many models once assumed.

A nearby stellar nursery, seen in new detail

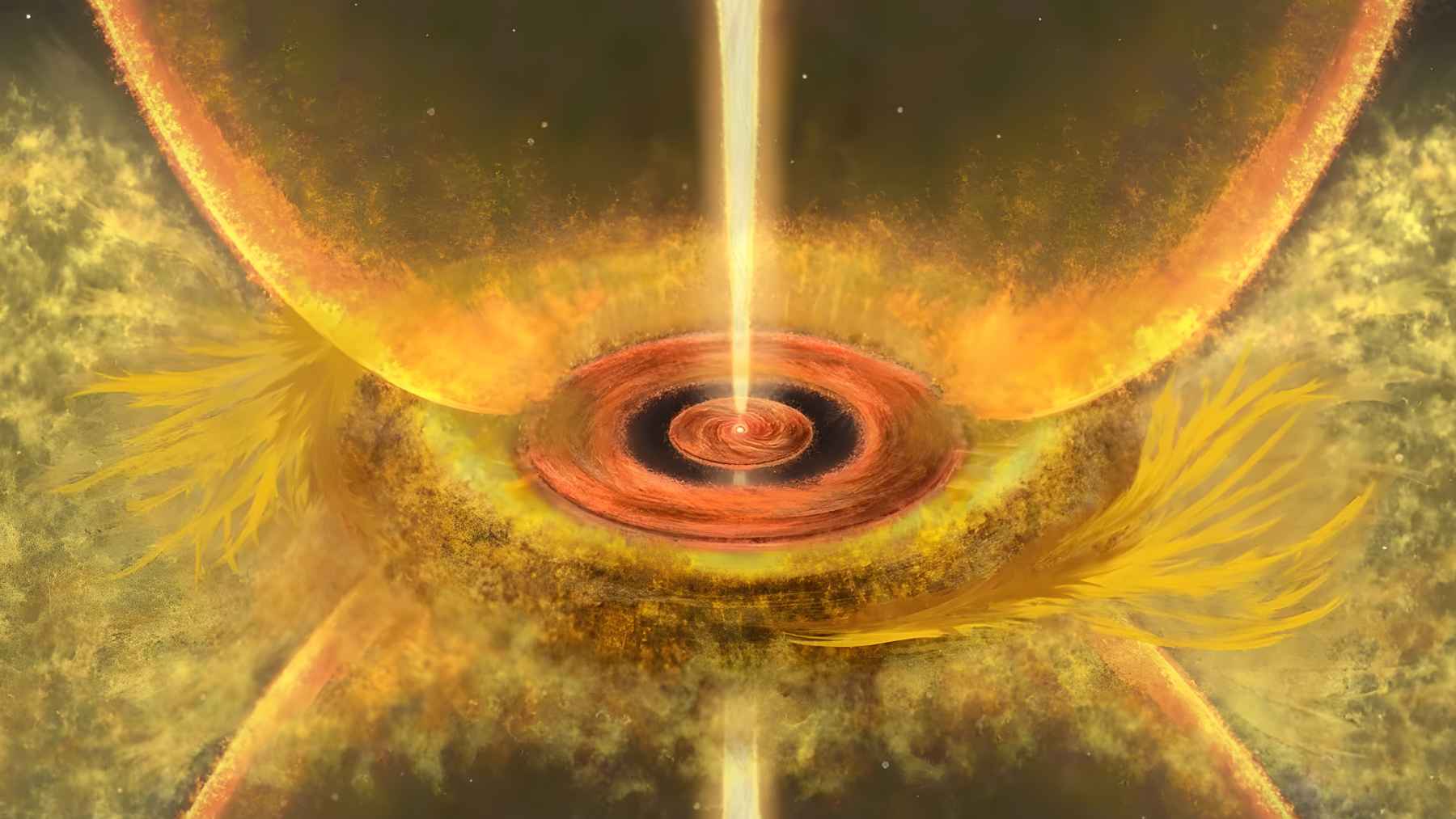

Planets form in cold, flattened disks of gas and dust that circle infant stars. These protoplanetary disks are the cosmic equivalent of cradles. The planets themselves are too small and faint to pick out directly, but their gravity sculpts the surrounding material into rings, gaps, and spiral patterns that astronomers can see.

The new study focuses on 78 such disks in the Ophiuchus molecular cloud, a busy stellar nursery about 460 light years from Earth. That is practically next door in galactic terms, close enough for ALMA to zoom in on the fine structure of the dust where rocky worlds could eventually emerge.

How astronomers sharpened the view

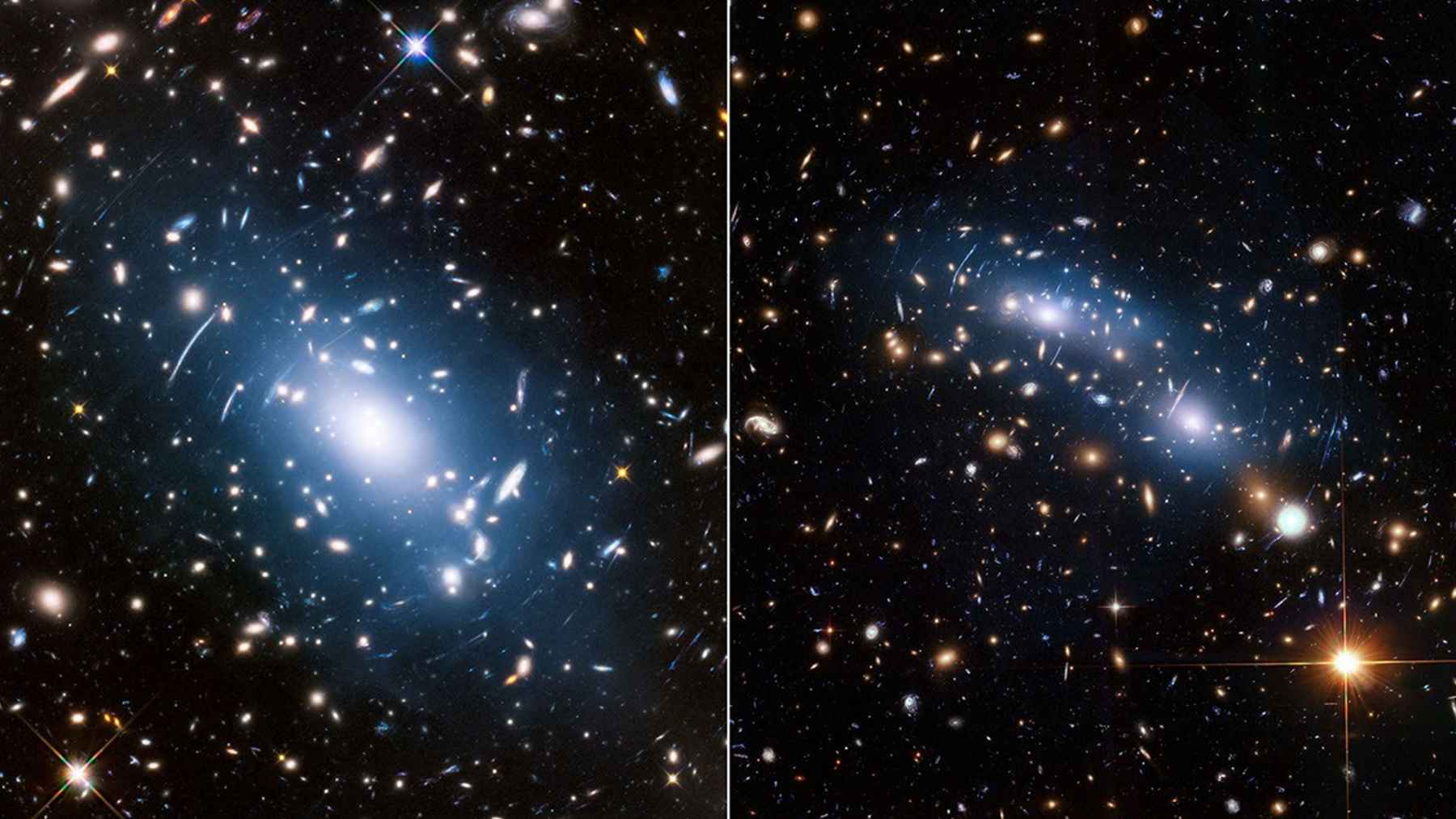

Instead of collecting new observations, the team turned to ALMA’s archive and applied a super-resolution imaging technique known as sparse modeling. In simple terms, it is a smarter way of filling in the gaps in interferometer data, using mathematical assumptions that better match how real disks look.

They used a public software package called PRIISM to rebuild the images. With the same raw data, more than half of the disks ended up with resolution more than three times sharper than in earlier analyses.

The new images rival the detail from previous flagship ALMA programs such as DSHARP and eDisk, while also quadrupling the total number of disks studied at this level of clarity.

Think of it as cleaning your glasses and suddenly realizing your living room was never as tidy as you thought. Structures that looked like smooth blobs in older maps now show crisp rings and twisted arms.

Rings, spirals and the first steps of planets

In the sharpened images, 27 of the 78 disks show obvious rings, gaps, or spiral features. 15 of those structured disks had never before been recognized as special. In rough terms, about one-third of the sample carries these fingerprints of growing planets.

These substructures appear even around stars that are only several hundred thousand years old. At that stage a young star is still wrapped in leftover material from its birth, and its disk is rich in gas and dust. The new work indicates that planets are already carving paths through this material while the star itself is still settling into maturity.

Lead author Ayumu Shoshi notes that the new images help “bridge the gap between the eDisk and DSHARP projects” and make it possible to study many more disks with comparable sharpness.

Pinpointing when structure appears

Earlier, the DSHARP survey showed that dramatic rings and gaps are common in disks around stars older than about one million years, while the eDisk program saw far fewer features around much younger, actively accreting protostars. That left a big question. When do the first clear signs of planet growth actually show up?

By combining the Ophiuchus sample with the eDisk targets, the team found a pattern. Substructures are detected mainly in disks larger than about 30 astronomical units in radius, and around stars whose bolometric temperature indicates ages of a few hundred thousand years or more.

In physical terms, that corresponds to systems that are still young, but no longer in the very earliest collapse phase.

The result points to a picture where planets and stars grow together in the same dusty environment, rather than planets assembling only after the disk has settled and thinned out.

Why this matters for life-bearing worlds

At first glance, this all happens unimaginably far away from everyday concerns like traffic jams or the electric bill.

Yet the timing of planet formation shapes what kinds of worlds can exist. If giant planets start forming while the gas disk is still thick, they can migrate, stir up smaller rocky bodies, and influence whether Earth-like planets end up in comfortable orbits where liquid water is possible.

Studies like this also show the power of reusing scientific data. By applying fresh algorithms to existing ALMA observations, researchers extracted new clues about the origin of planetary systems, including our own, without building a single new antenna. It is a bit like finding a whole new chapter in a book you thought you had already finished.

The study was published in Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan.