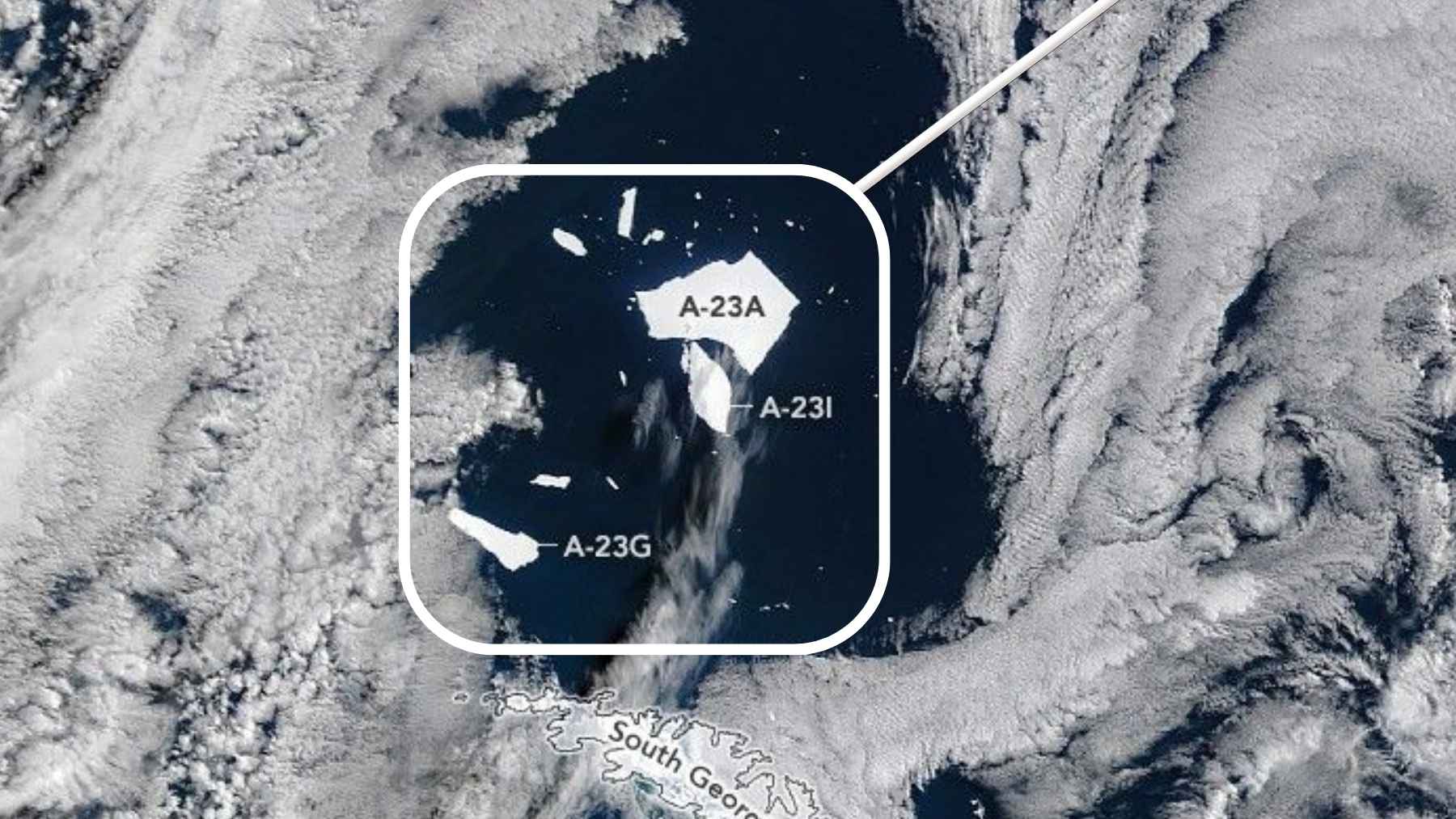

A slab of ice bigger than New York City is quietly falling apart in the South Atlantic. Iceberg A-23A, one of the largest and longest lived icebergs ever tracked, is now riddled with bright blue meltwater ponds and scientists say it is “on the verge of complete disintegration” as the austral summer wears on. After nearly forty years at sea, the megaberg is running out of time.

NASA Terra satellite images show rapid meltwater pooling

Recent satellite images from NASA’s Terra spacecraft show A-23A streaked with turquoise pools that sit in shallow depressions and old fractures on the surface. Those pools are not just pretty. Liquid water is much heavier than snow, so as it gathers in cracks it pushes them wider and helps the berg crumble into smaller pieces.

Senior research scientist Ted Scambos explains that the weight of meltwater is “sitting inside cracks in the ice and forcing them open”. Analysts estimate the iceberg now covers about 1,182 square kilometers, down from roughly 4,000 square kilometers when it calved from Antarctica’s Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986.

International Space Station photos reveal rampart moat pattern

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station caught the same scene from above and reported even larger melt ponds just one day after the satellite view. In those photos, almost the entire top of A-23A looks like a patchwork of vivid blue except for a thin white rim along the outer edge.

Ice specialists describe that pattern as a “rampart moat” effect, where the edges of the berg bend slightly upward as they melt and briefly trap water near the center.

Ancient glacier striations still guide meltwater flow

Look closely at the imagery and you notice long, straight streaks of alternating blue and white. Those are not new scars. Scientists think they trace back hundreds of years to the time when this ice was part of a glacier scraping across Antarctic bedrock.

That slow grinding carved subtle ridges and valleys that still steer the flow of meltwater and quietly shape how this modern iceberg falls apart.

A long drift through iceberg alley and a Taylor column trap

A-23A’s road to this moment has been unusually complicated. After it broke away from the ice shelf in 1986, the berg ran aground in the shallow Weddell Sea and stayed pinned to the seafloor for more than three decades. It finally broke free around 2020 and headed north into “iceberg alley,” where most Antarctic icebergs eventually drift into the South Atlantic.

In 2024, currents over a seafloor bump trapped it again inside a spinning column of water known as a Taylor column, where it looped in place for months before “spinning out” and resuming its northeastward path.

Why iceberg freshwater matters for ocean currents and ecosystems

So what does a blue iceberg thousands of miles from any city have to do with everyday life? Events like this help scientists understand how giant icebergs, sometimes called megabergs, break up and release freshwater into the ocean. When a berg melts, it can briefly freshen surface waters, nudge local currents, and stir up nutrients that feed plankton at the base of the marine food web.

Those details matter for climate models, shipping routes, and even wildlife, since some bergs can block or reshape access to feeding grounds for penguins and seals.

Antarctic sea ice trends and what scientists are watching in 2025

A-23A’s final chapter is unfolding at the same time that Antarctic sea ice has been behaving in unusual ways. Satellite records show that the 2025 winter maximum around the continent was the third lowest in nearly half a century of observations, and summer sea ice has also dipped to near record lows in recent years. Scientists are careful not to blame any single iceberg on climate change, yet many point out that a warmer atmosphere and especially a warmer ocean are likely helping tip the balance toward thinner ice, shorter seasons of sea ice cover, and faster melt in many parts of the Southern Ocean.

For most of us, this breakup will never show up on a weather app or an electric bill. Yet the same satellites that watch our storms and heat waves are also tracking A-23A as it comes apart, adding one more piece to the puzzle of how a warming planet reshapes the polar seas.

The official statement was published on NASA Earth Observatory.