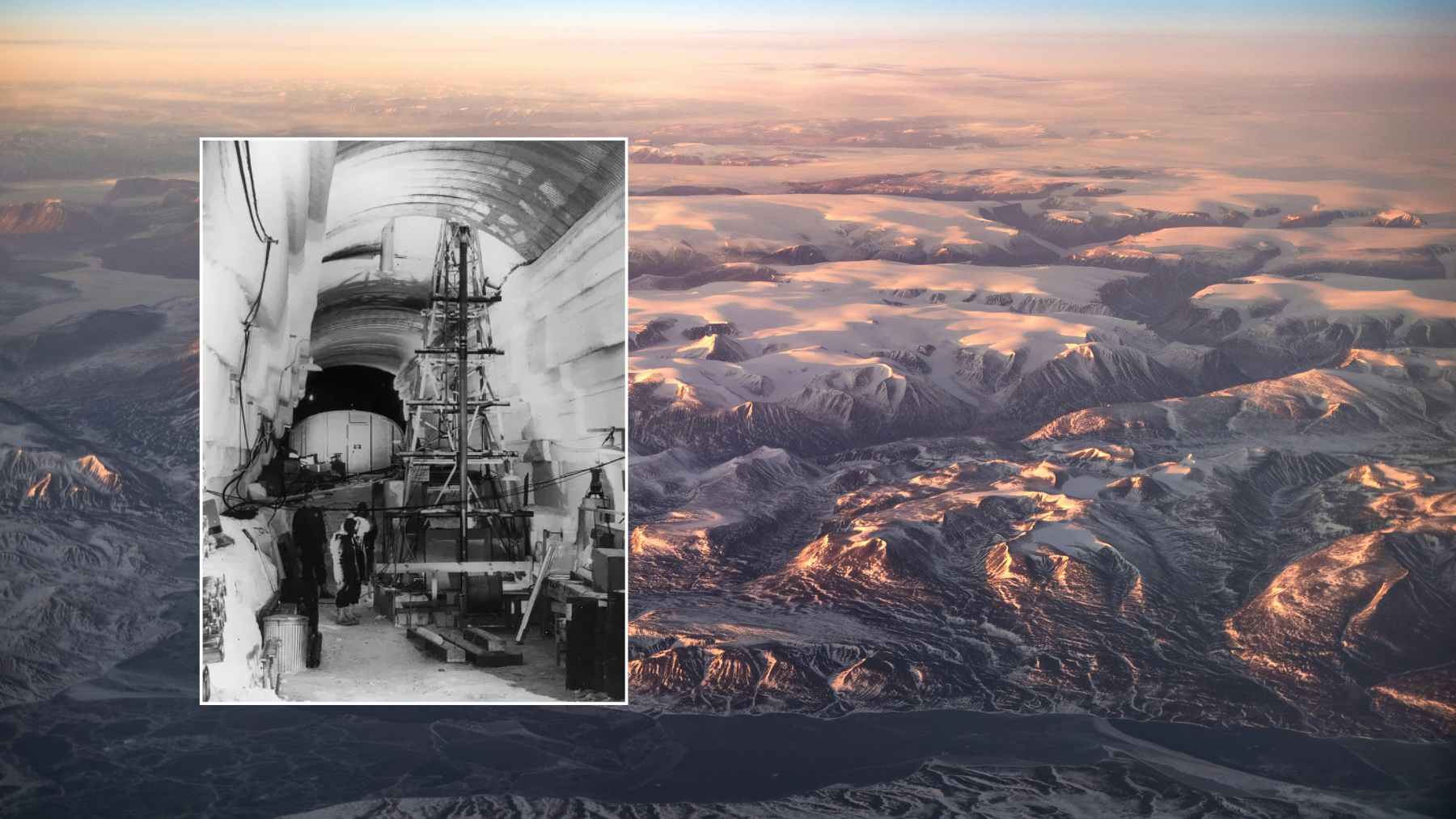

A routine research flight over Greenland has turned up an unexpected reminder of the Cold War. Scientists mapped a clear outline of Camp Century, an abandoned U.S. military site now buried about 100 feet under the ice.

The base itself is not the big surprise. What’s grabbing attention is what stayed behind after it shut down, including radioactive waste that was assumed it would never see daylight again. With Greenland warming over time, that old assumption is starting to look shaky.

A “city under the ice” shows up on a radar scan

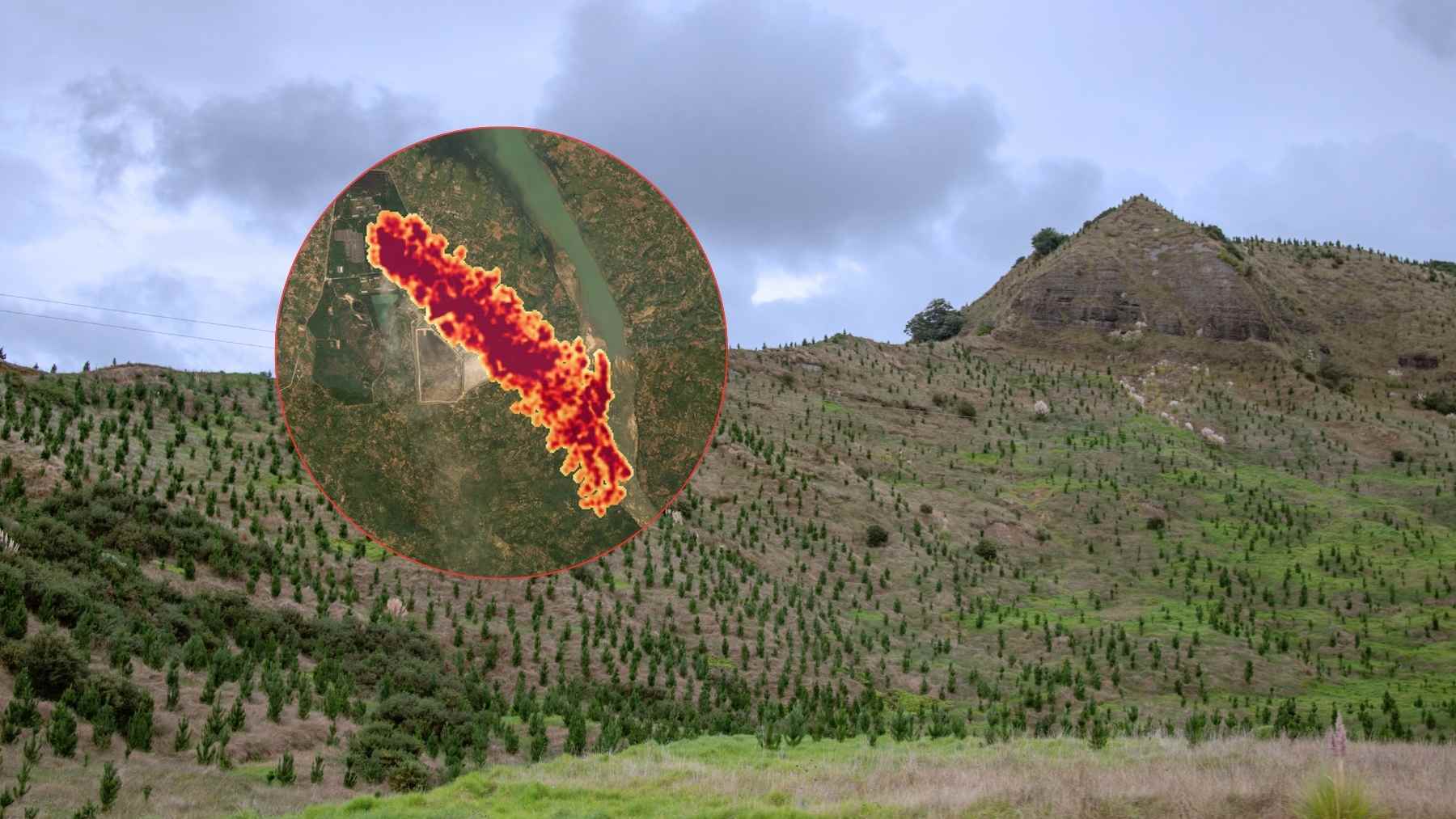

In April 2024, an airborne survey captured unusually sharp radar images of structures hidden inside the Greenland Ice Sheet. The main investigator, Chad Greene, later helped confirm the shapes matched Camp Century, a sprawling complex built directly into the ice.

The radar system used was Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar, or UAVSAR. In simple terms, it sends radio waves into the ice and measures the echoes, a bit like yelling in a tunnel and judging distance by the sound that comes back. That’s how researchers could “see” tunnels and rooms without drilling down.

Why the U.S. built it, and why Denmark mattered

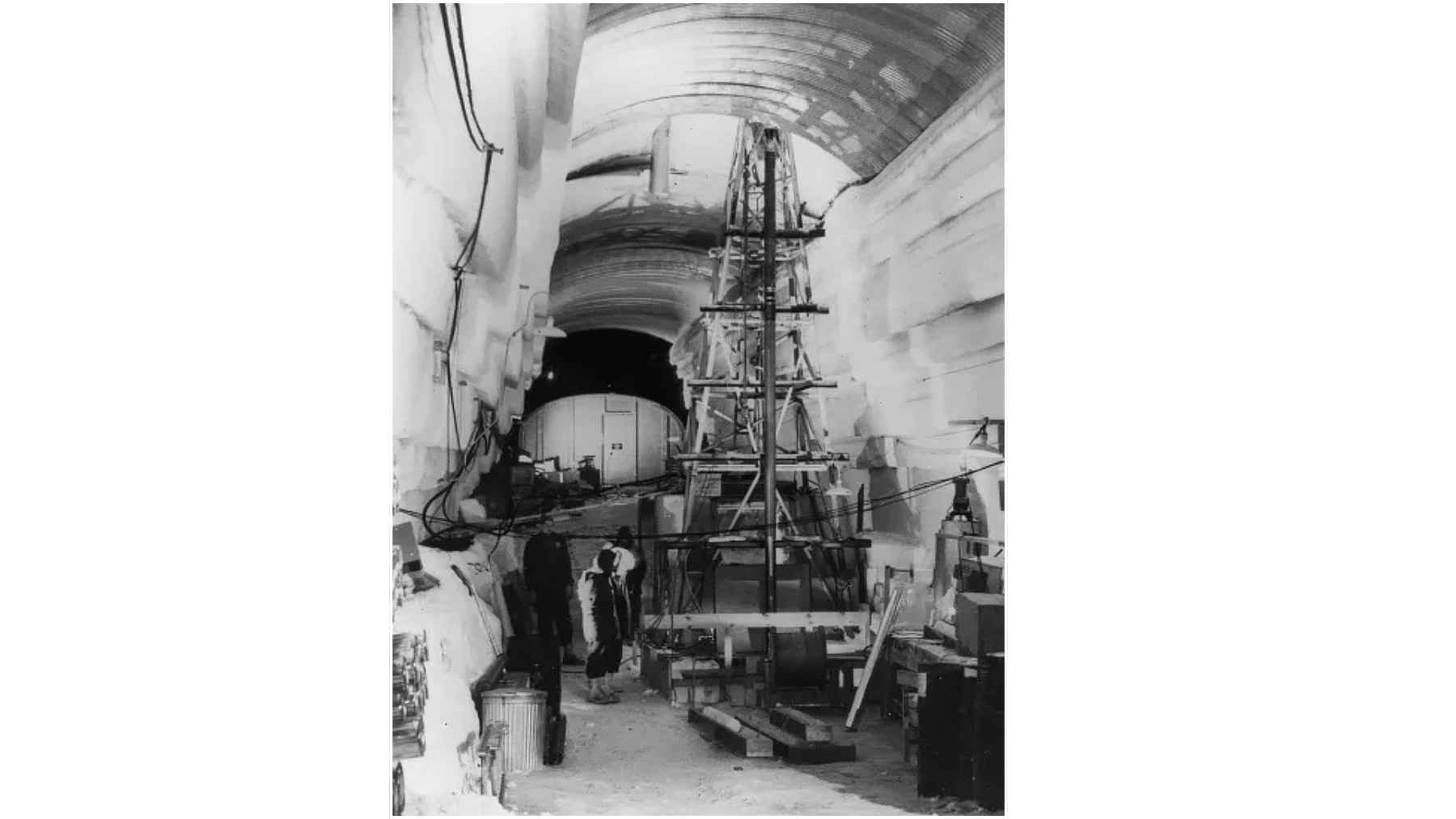

Camp Century was constructed in 1959 and presented publicly as a scientific and engineering outpost in extreme Arctic conditions. Behind the scenes, it also served as a stepping stone for planning a much larger missile concept under the ice, part of the era’s high-stakes nuclear strategy.

Its existence was tied to a broader legal framework that allowed American forces to operate in Greenland for North Atlantic defense. The 1951 Defense of Greenland agreement spelled out how U.S. facilities could be used in cooperation with Denmark, which governed Greenland at the time.

It’s a strange thought, honestly. How does a military project big enough to carve a hidden settlement into a glacier end up becoming a half-forgotten relic?

The waste that did not leave with the reactor

Camp Century once ran on a portable nuclear reactor, an engineering flex that came with an obvious downside. When operations ended, the reactor was removed, but large amounts of radioactive wastewater and other leftover materials were not, including more than 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste cited in historical summaries.

The practical reason was simple. Back then, many planners believed the site would stay sealed under snow and ice indefinitely, making removal feel less urgent.

Climate scientists now look at that decision differently, because “permanently buried” is not the same as “permanently safe.”

A warming future could turn a frozen problem into a real one

A 2016 paper led by William Colgan of York University modeled how local ice conditions could shift from building up over time to melting away later this century under plausible warming scenarios. In other words, the ice that has acted like a lid could eventually start thinning instead of thickening.

That does not mean waste suddenly spills out tomorrow. But it does raise an uncomfortable question for the long run, especially as Greenland’s ice loss becomes a regular part of climate reporting, not some distant “maybe.”

For most people, this story lands somewhere between spy history and environmental risk. It’s like finding an old, locked storage unit in your building, then realizing the lock might not hold forever.

The main official release was published by NASA Earth Observatory.