When a volcano erupts, it seems like nothing could survive in the path of the glowing lava. Yet a new study shows that microscopic life rushes back far faster than scientists expected, grabbing hold of newborn rock only hours after it cools. So who are the first survivors to come back?

By tracking microbes on lava flows from Iceland’s Fagradalsfjall volcano between 2021 and 2023, researchers watched a dead landscape turn into a living one almost in real time. Could their findings reshape how we think about the start of ecosystems on Earth and even about where to look for life on Mars?

How life returns after a volcanic wipeout

“The lava coming out of the ground is over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit,” lead author Nathan Hadland explained, describing it as a clean slate for life. To scientists, that makes each fresh flow a natural experiment in how life begins again from zero.

Until now, most research on volcanic landscapes focused on plants, animals, or microbes that moved in long after the eruption had ended. This new work instead zooms in on the very first wave of colonization, known as primary succession, when organisms claim a brand new habitat for the first time.

It is the first detailed look at how microbial communities assemble on rock that is still cooling and cracking.

A rare natural lab in Iceland

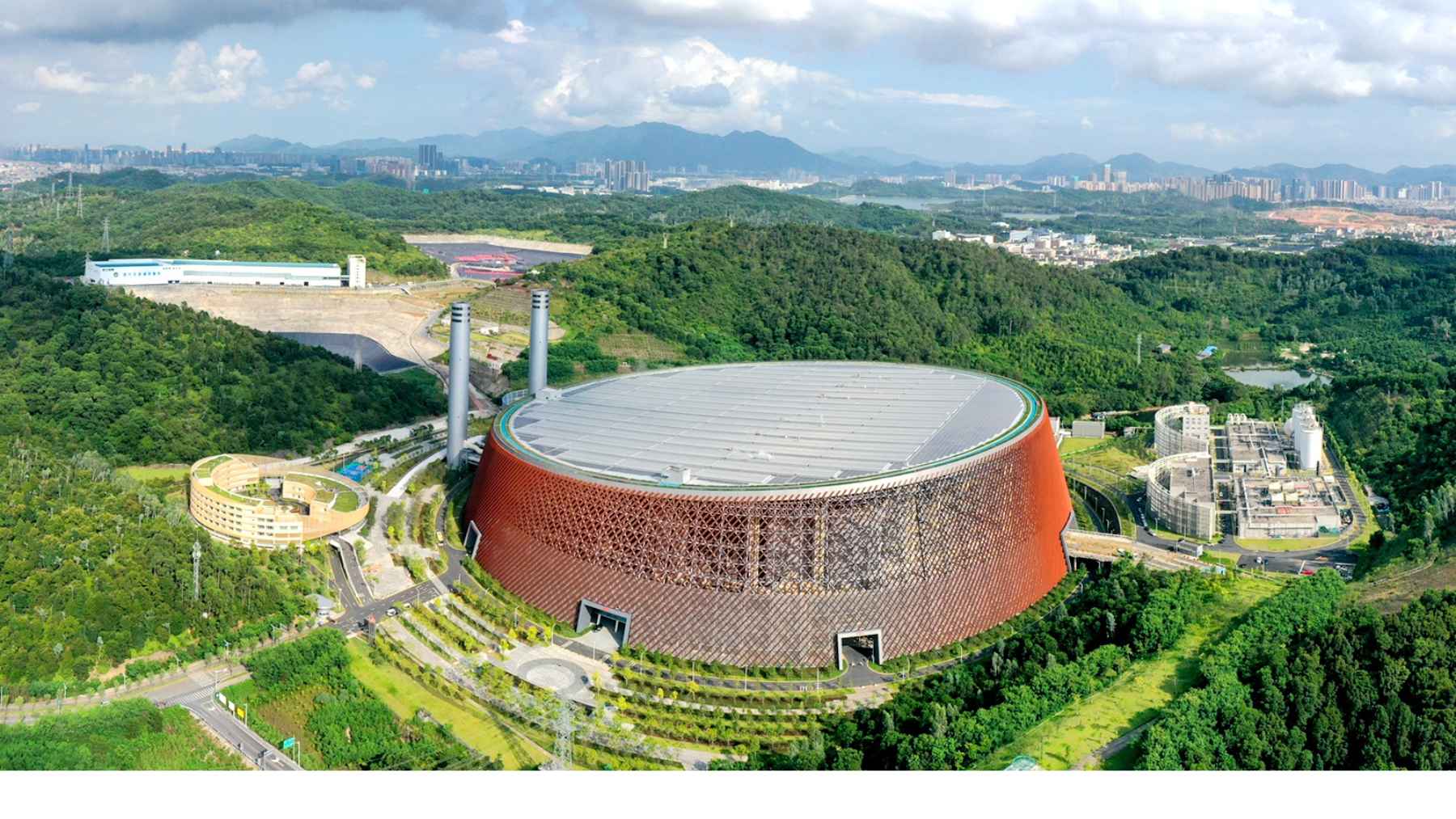

The team, led by researchers from the University of Arizona together with colleagues at the University of Iceland, chose the Fagradalsfjall volcano on the Reykjanes Peninsula because it erupted three times over three years, creating repeated fresh flows in nearly the same place.

Scientists hiked out over the jagged black rock again and again, sometimes scooping up lava that had cooled only a few hours earlier. In practical terms, they were visiting a newborn world that kept resetting itself.

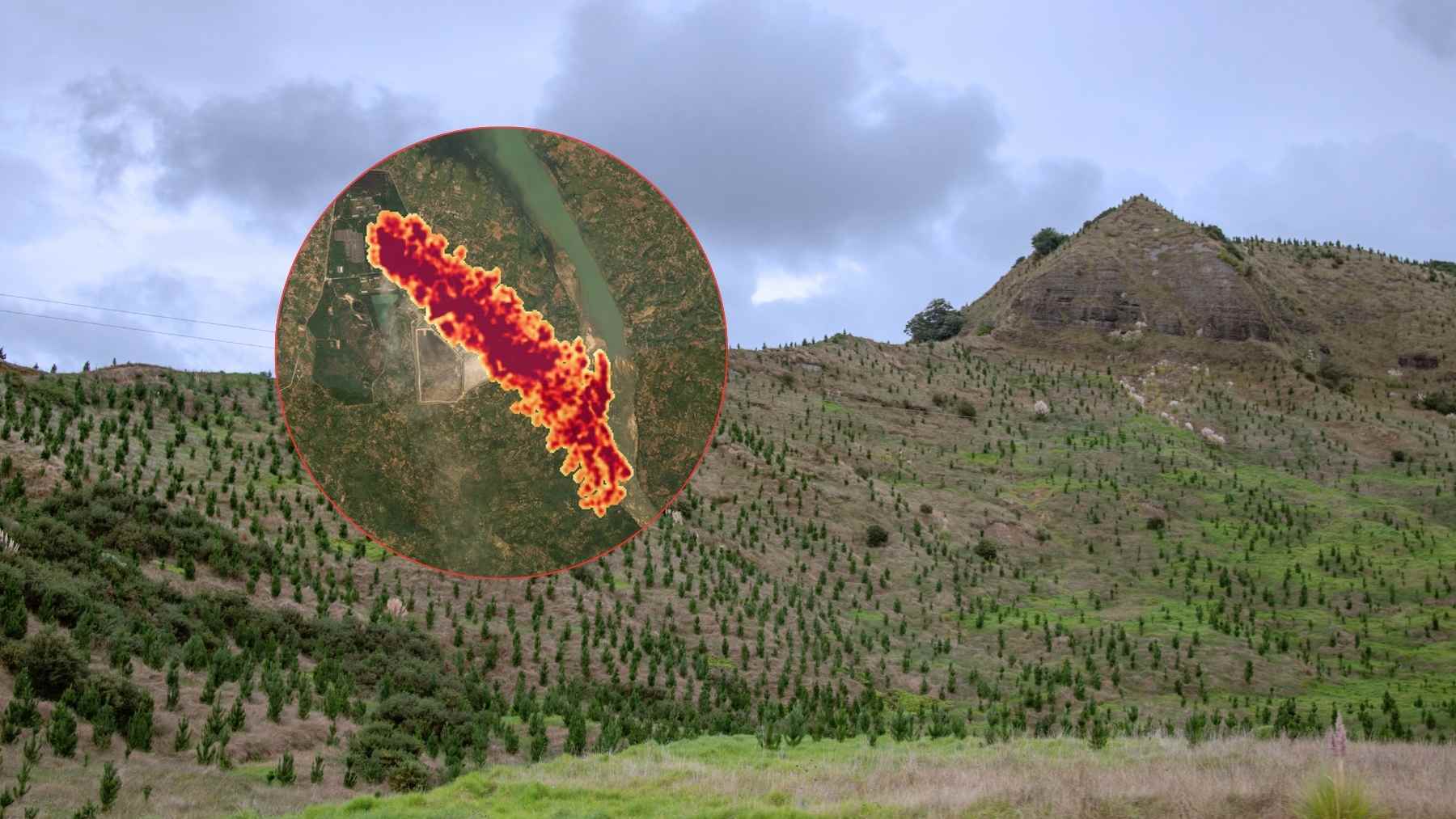

They collected pieces of lava, rainwater, and tiny airborne particles, along with soil and older rocks from nearby slopes in Iceland. Back in the lab, they extracted DNA from those samples to identify which microbes were present and where they had come from. That allowed them to follow the arrivals like new residents moving into a just-built neighborhood.

Tough pioneer microbes move in fast

The surprise was how quickly those residents showed up. Within hours and days of a flow solidifying, the once-sterile rock was already dotted with microbial DNA, even though it held almost no water or organic nutrients, and many of the newcomers seemed to ride in with wind-blown dust and the first rain showers.

Later in the study, most arrivals appeared to be coming in with rainwater seeping into cracks in the rock.

Co-author Solange Duhamel described these first arrivals as tough microbes that tolerate dryness, cold, and hunger better than most others.

Single celled organisms were “colonizing them pretty quickly,” she said, even in what counts as one of the lowest biomass environments on Earth. Over the following months, as more rain fell and seasons changed, new species joined and the community began to stabilize.

A reset that repeats again and again

Because the same volcanic system erupted again in 2022 and 2023, the scientists could watch the process restart. Each time, they saw a similar pattern, a burst of diverse microbes in the first year, followed by a sharp drop in diversity after the first winter, then a slower buildup.

That repeat performance suggested the colonization process is not random but follows rules that can be predicted.

Using statistical tools, the team found evidence for a two-step story. First comes a chaotic rush of hardy pioneers from many sources that test the new habitat.

Then, as cold, darkness, and limited nutrients filter out the less-suited species, a more stable and specialized community takes over, a bit like a town settling down after the initial construction noise fades.

Clues for life on Mars and other worlds

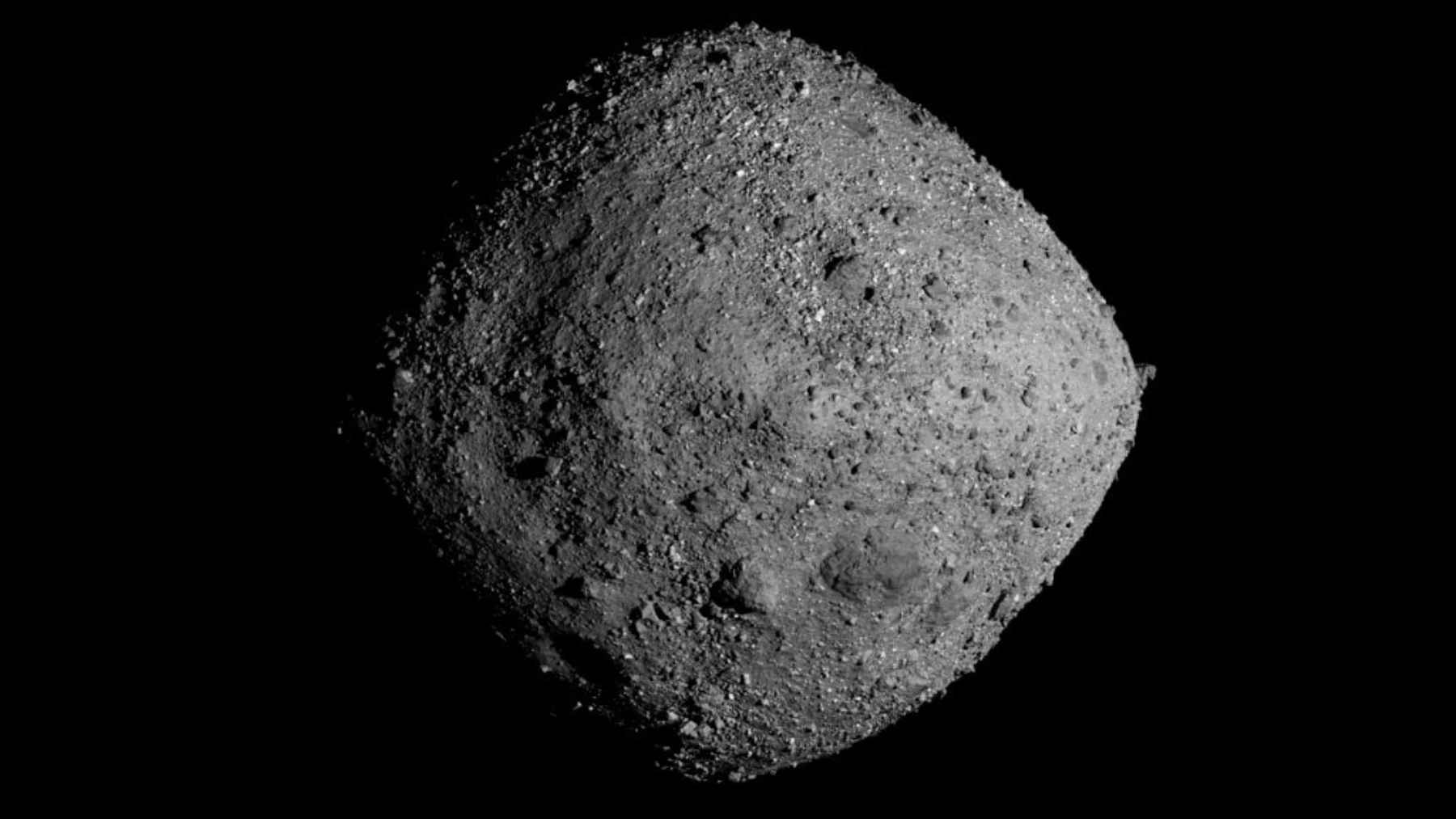

For planetary scientists, these results offer a new way to think about life on worlds shaped by volcanoes. Much of the Martian surface is made of basaltic rock that formed through past eruptions, and there are vast lava plains and ancient volcanic mountains there.

If microbes on Earth can seize bare lava so fast, similar organisms could in theory do the same anywhere that liquid water and the right chemicals are available.

Duhamel notes that volcanic activity adds heat, releases gases, and can melt buried ice, briefly creating pockets where life might gain a foothold. On Mars, past eruptions might have produced short windows of habitability in otherwise harsh terrain. Studies like this help researchers decide which rocks, minerals, and ancient lava flows future missions should target when they hunt for traces of past microbial life.

Why fresh lava microbes matter back on Earth

The work also fills in a missing chapter in the story of how ecosystems recover after disasters. Microbes are often the first colonists on bare stone, and over time they help trap dust, cycle nutrients, and prepare the way for mosses, grasses, and eventually shrubs and trees. In a slow, quiet way, they turn hot black rock into the kind of soil where life we recognize can take root.

Volcanic terrains already serve as test beds for understanding how life adapts to extremes, from Icelandic lava fields to hot springs and fumaroles studied in earlier research. By watching microbes claim a brand-new lava flow almost as soon as it cools, scientists gain a clearer view of life’s resilience and the rules that shape new communities.

The main study has been published in Communications Biology.