New German alloy stays strong near 2,000°F, a possible boost for hotter jet engines

A research team in Germany says it has created a metal alloy that can take the kind of heat that usually ruins turbine parts. The material stayed tough and resisted oxidation in air at temperatures close to 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, a range that pushes today’s best engine metals to their limits.

Why does that matter to anyone outside a lab? Because hotter turbines can squeeze more useful work out of the same fuel, which can mean lower emissions and, over time, cheaper power and fewer gallons burned on a flight. The results were reported by Frauke Hinrichs and colleagues, and the next question is the one engineers always ask. Can it survive the messy reality of a working engine?

Why heat still decides how efficient engines can be

In simple terms, engines and power turbines get more efficient as their hottest gas gets hotter. That is why designers keep chasing higher turbine inlet temperatures, even though the metal parts themselves cannot safely match those gas temperatures without heavy cooling.

Nickel-based superalloys are the current workhorses for turbine blades and vanes, and they are already operating close to their practical ceiling in the hottest zones. If you have ever wondered why engineers obsess over cooling holes and coatings, this is the reason. A small temperature gain can ripple into fuel savings that show up everywhere, from the electric bill to the cost of moving people and goods.

What makes this recipe different from earlier high-heat metals

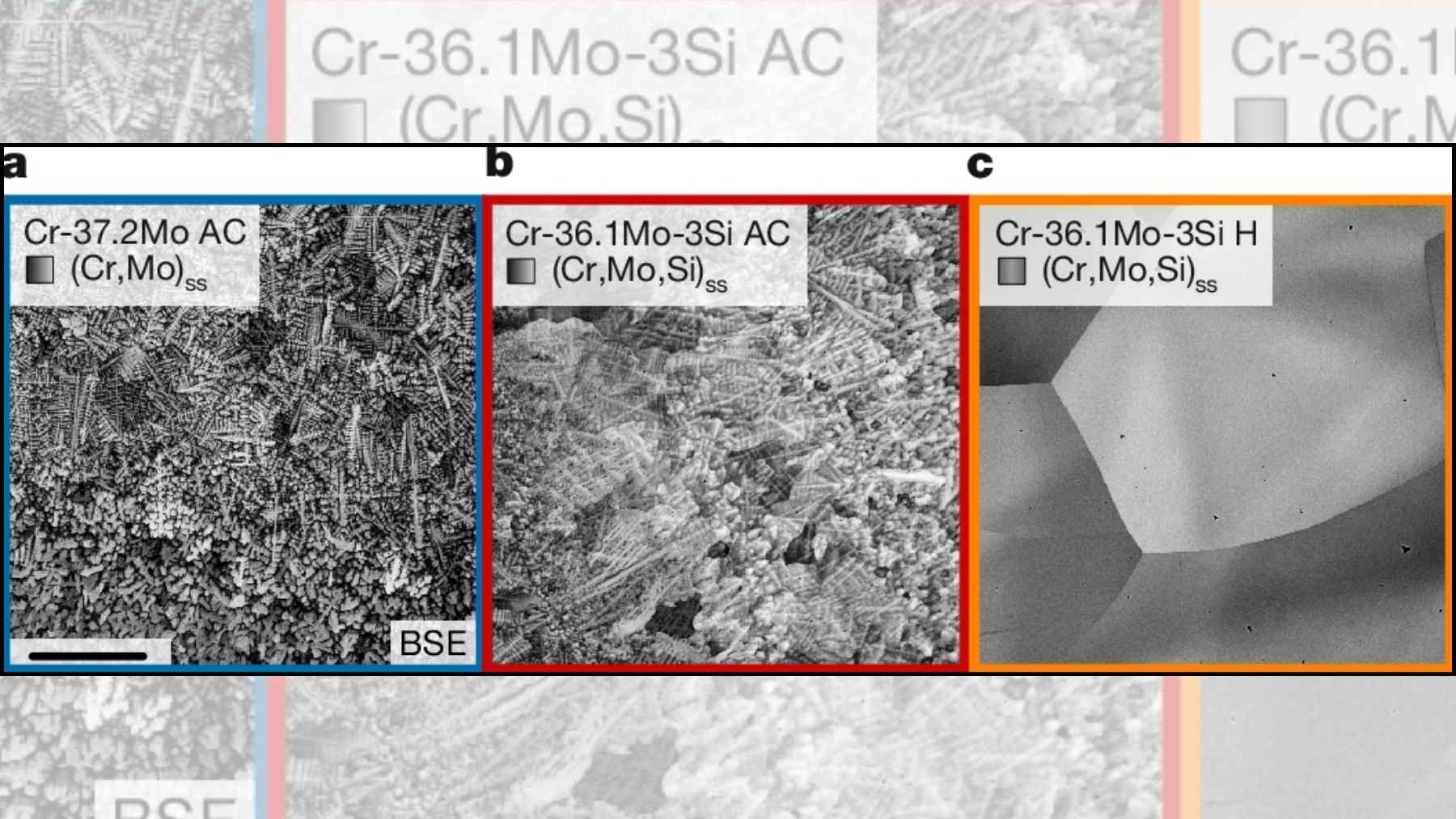

The new material is a chromium–molybdenum–silicon alloy designed to stay as a single, uniform phase instead of splitting into hard, brittle chunks. In everyday language, it is meant to behave like one consistent metal, not a patchwork that cracks when stressed.

That “one-phase” choice matters because many previous chromium and molybdenum designs depended on large amounts of silicides, which can protect against oxidation but often make the metal fragile at room temperature. In tests that ran for about 100 hours in repeated high-heat cycles, samples held their shape and developed a slow-growing protective layer rather than crumbling away.

How it resists oxidation without flaking apart

Oxidation is basically rusting at high heat, and turbine environments are perfect for it. The alloy’s protection comes from forming a thin chromia layer, a tight “skin” of chromium oxide that blocks oxygen from digging deeper into the metal. The key is that the skin sticks, since flaking would expose fresh metal and speed up damage.

A small amount of silicon also plays a quiet but important role by encouraging a trace of silica at the boundary between the metal and its oxide layer. That helps keep the surface chemistry stable and reduces a nasty failure mode called pesting, where molybdenum-rich materials can rapidly crumble as volatile oxides escape. It also helps limit nitridation, which is when nitrogen works its way into hot metal and makes it more brittle over time.

What has to happen before it can fly or power the grid

Lab samples are not turbine blades, and turning this into real hardware will take years of careful work. The team’s advantage is simplicity, since a single-phase alloy can be easier to scale through methods like powder metallurgy, where fine metal powders are fused into dense parts, or through additive manufacturing when heat control is precise.

Still, big hurdles remain, including long-term creep testing, which measures slow sagging under constant load at high heat, and oxidation trials in more realistic exhaust that includes water vapor and combustion byproducts. “They are ductile at room temperature, stable at high temperatures, and resistant to oxidation,” said Martin Heilmaier from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, summing up the rare combination the team was aiming for. If that balance holds up under vibration, thermal gradients, and contaminants, it could open new temperature headroom that turbine designers have been chasing for decades.

The main study has been published in Nature.

Photo: Chiara Bellamoli, KIT.