Two almost perfectly round dinosaur eggs from eastern China have turned out to be hollow shells packed with glittering crystals instead of bones. The fossils, uncovered in the Qianshan Basin of Anhui Province, belong to a newly named egg species called Shixingoolithus qianshanensis and are helping scientists piece together how plant-eating dinosaurs nested in the final chapters of the Cretaceous period.

Each egg is about 13 centimeters wide, roughly the size of a small cannonball. One cracked open naturally in the rock, revealing clusters of pale calcite that sparkle like the inside of a geode. Researchers report that the shells are empty cavities lined with these mineral crystals rather than embryonic bone.

Cannonball-sized eggs that became natural geodes

After the eggs were laid and buried, their original contents appear to have decayed or drained away. Groundwater rich in dissolved calcium carbonate seeped through the surrounding sediments and into the empty shells. Over millions of years, that mineral-laden water slowly deposited calcite crystals along the inner surface, turning each egg into a natural geode with a thin dinosaur shell as its outer wall.

From the outside, the fossils look like weathered gray stones with little ornamentation. Inside, the crystal growth records a long history of fluid movement through the Qianshan Basin, a continental sedimentary basin that spans the transition from Late Cretaceous to early Paleocene times and is better known for fossil mammals, reptiles, and birds than for dinosaurs.

A new dinosaur species known from eggs only

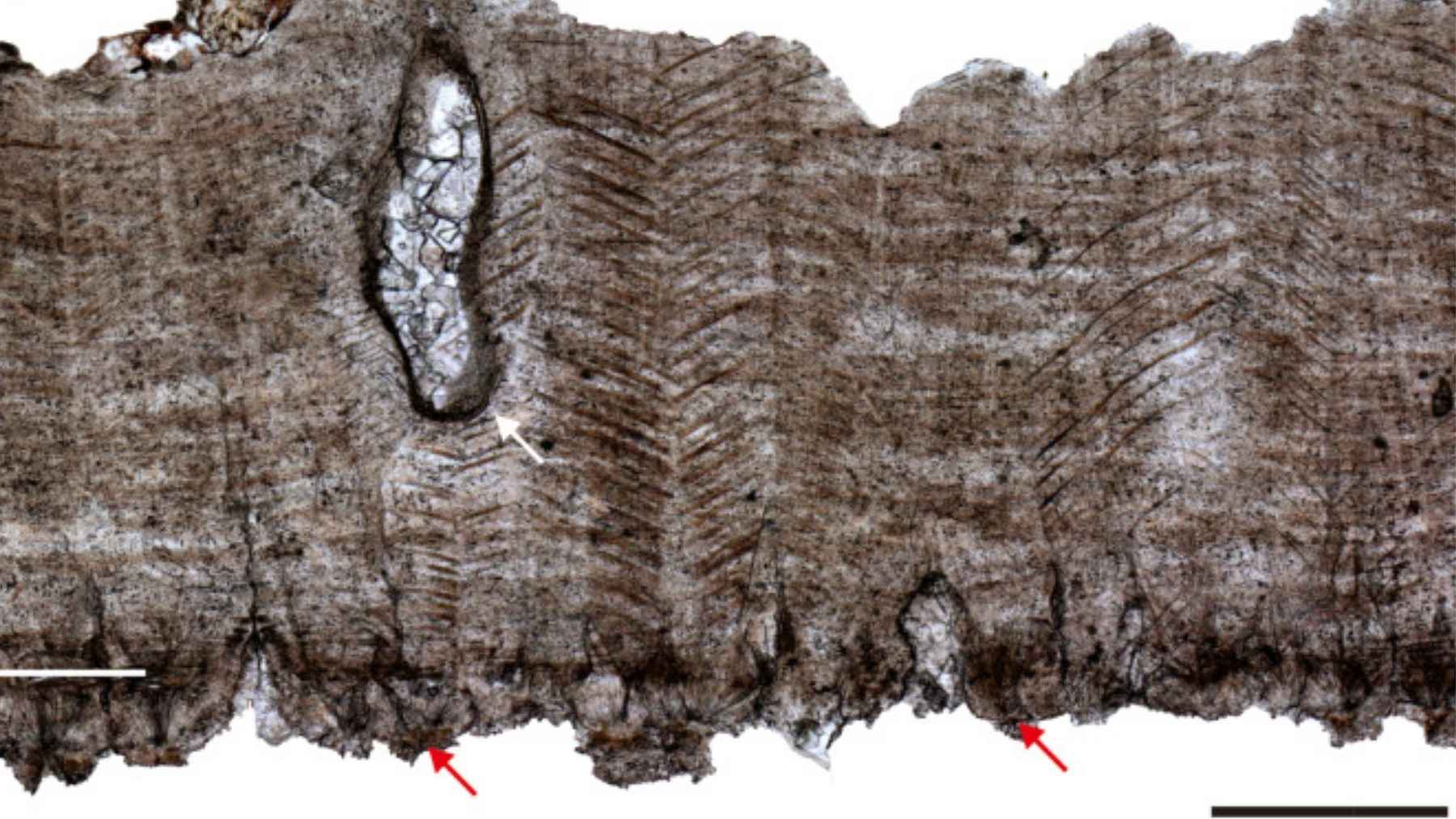

To understand what kind of dinosaur laid these unusual eggs, the team studied thin sections of shell under the microscope. The eggs are nearly spherical and have very thick shells made of densely packed columnar units with a uniform microstructure and a high density of tiny radial features on the inner surface. Those traits match an oofamily called Stalicoolithidae, which groups thick-shelled, round dinosaur eggs that usually occur in tight clusters.

On that basis, paleontologist Qing He and colleagues defined a new oospecies, Shixingoolithus qianshanensis, in a 2022 study in the Journal of Palaeogeography. They wrote that “New oospecies Shixingoolithus qianshanensis represents the first discovery of oogenus Shixingoolithus from the Qianshan Basin,” and that these eggs provide key evidence for classifying local rock layers that straddle the dinosaur extinction horizon.

No embryo is preserved, so the parent cannot be identified with certainty. Shell size and shape, together with comparisons to better-known eggs, point toward an ornithopod dinosaur, a fast running herbivore with a broad, duck-like snout that commonly reached six to nine meters in length and disappeared in the mass extinction that followed the Chicxulub impact.

Crystals as tiny climate archives

At first glance the crystals might seem like a geological curiosity with little biological value. Recent work at another Chinese site suggests otherwise. In central China, a separate team studied a clutch of 28 dinosaur eggs whose interiors are also filled with large calcite crystals. Trace uranium trapped in those crystals allowed researchers to apply uranium lead dating directly to the eggs and pin down their age at about 86 million years.

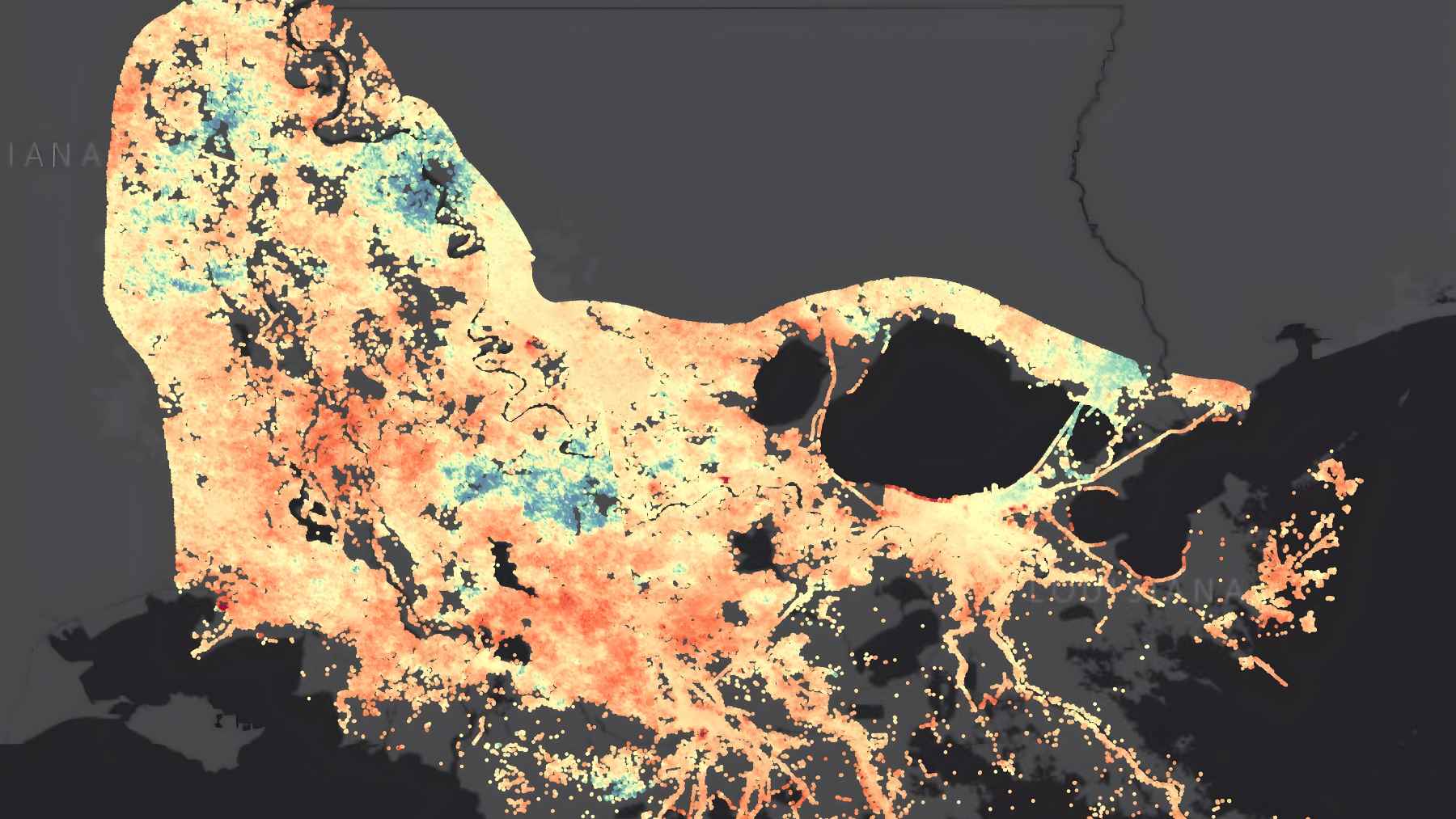

By matching those ages and the eggshell pore structures with records of global cooling during the Late Cretaceous, scientists showed that egg anatomy can respond to long-term climate shifts, for example through changes in porosity that regulate gas exchange in warmer or cooler conditions. The study concluded that dinosaur egg fossils can act as “proxies for reconstructing the Cretaceous world” on land, linking nest microenvironments to broader climate trends.

The Qianshan crystal-filled eggs have not yet been dated with that technique, but they share the same basic recipe. Biological shells became mineral laboratories, preserving information about groundwater chemistry, burial conditions, and the timing of sediment build up. That makes each egg a tiny archive of environmental change near the end of the age of dinosaurs.

What these ancient nests mean for us today

Eastern China has earned a reputation as a fossil hotspot where soft tissues, feathers, and even stomach contents can survive. Volcanic ash and fine sediments repeatedly smothered ecosystems, sealing out oxygen and slowing decay.

Regions such as the Jehol biota in the northeast and basins like Qianshan in the east now yield exquisitely preserved eggs, embryos, and whole communities that let scientists rebuild ancient forests, lakes, and floodplains in remarkable detail.

For today’s climate researchers, these discoveries are more than spectacular museum pieces. When egg layers are tied to volcanic ash beds, fossil plants, and precise radiometric dates, they show how animals coped with gradual cooling long before the final asteroid strike. That kind of deep time experiment helps scientists test ideas about how modern species may respond to rapid warming, shifting rainfall, and other stresses that now show up in our own environmental records.

Next time you see a dull gray stone in a case at a natural history museum, it might be one of these glittering cannonball-sized eggs. Inside, the crystals are quietly holding on to stories about dinosaur parents, vanished climates, and the long conversation between life and the planet that continues today.

The study was published in Journal of Palaeogeography.