A few inches is nothing, until it’s the ground under your feet doing the stretching. Most of us notice movement in everyday ways: a sticking door, a hairline crack, a floorboard that suddenly squeaks. Now picture a mountain in southeastern Iran doing something similar.

Satellite measurements show Taftan volcano’s summit area rose by about 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) over roughly 10 months, from July 2023 to May 2024. Researchers say the uplift likely reflects pressure building in the volcano’s shallow plumbing, not a guarantee of an eruption. Still, it’s the kind of quiet change that makes scientists lean in, because it can signal shifting conditions underground.

Is Taftan volcano in southeastern Iran actually moving?

Yes, at least on a scale that satellites can pick up. In a 2025 study, researchers used satellite radar to detect localized uplift at Taftan’s summit that started and ended gradually over a 10-month span. Importantly, the study reports no clear “bounce back” afterward, which suggests elevated pressure conditions may have persisted rather than quickly relaxing. Here’s the situation in plain terms:

| Key detail | What researchers reported |

| Amount of uplift | About 9 cm (3.5 inches) near the summit |

| Timing | July 2023 to May 2024 (about 10 months) |

| Suggested depth of pressure source | Roughly 460–630 m below the surface |

| Likely driver | Internal processes, not rainfall or earthquakes |

| Why it matters | No post-unrest subsidence, plus mention of increased gas emissions and potential hazards |

That “quiet for ages” framing also has some grounding. The researchers note Taftan lacks evidence for Holocene eruptions and cite dated materials around 0.71 ± 0.03 million years old. They also note a report of increased fumarolic activity in May 2024. Translation: it’s not a brand-new volcano, but it’s also not a dead rock.

How did Sentinel-1 radar spot a 3.5-inch change from space?

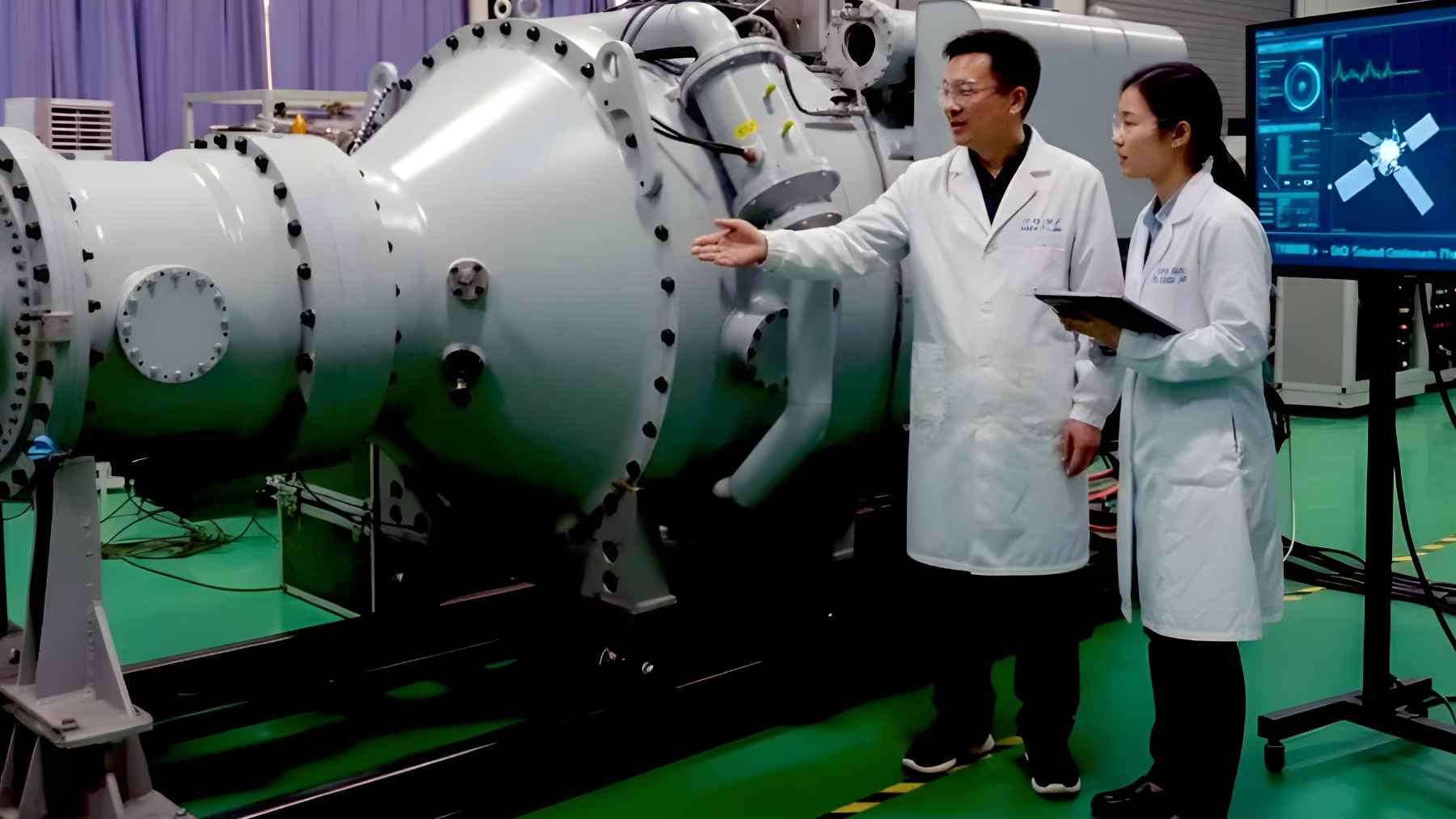

The key tool here is InSAR (short for Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar), which is basically a way to compare radar images taken at different times to measure tiny ground motion. Instead of someone hiking up with a tape measure, the satellites do repeat passes and scientists look for patterns that imply the ground rose or sank.

Sentinel-1 is built for this kind of work because it carries radar that can collect imagery day or night and in all weather, including through clouds. This is key in places where on-the-ground monitoring is limited, because the satellite does not care if the volcano is remote or if the weather is being difficult.

What could be building pressure under the summit, and does this mean an eruption?

First, the study says this episode was “triggerless,” meaning it did not line up with rainfall or seismic events as obvious outside causes. That points scientists back to what’s happening inside the volcano itself.

The authors favor two internal scenarios. One is a hydrothermal system (hot water and gas moving through cracks underground) changing over time: permeability shifts could let gas build up at shallow depth, pressurize, and then partially vent as pathways open.

The second is a minor, undetected magmatic intrusion (new molten rock moving at depth) that could release gases and raise pressure in the hydrothermal zone.

None of that automatically equals “eruption incoming.” But the paper flags non-negligible phreatic potential, meaning steam-driven explosions that can happen when hot fluids flash into vapor near the surface. Those events can be sudden, and they are one reason scientists push for monitoring even when lava is not on the menu.

What should nearby communities and local officials do now?

The study’s bottom-line policy message is not subtle: revise the local volcanic-risk picture and invest in risk reduction, including monitoring networks and hazard maps. Yes, that means paperwork and budgets. Practical steps people can take if they live near Taftan or downwind include:

- Follow guidance from local authorities and emergency management, especially if advisories change quickly.

- Pay attention to strong sulfur odors and avoid approaching vents or fumarole areas if conditions seem abnormal.

- Keep basic respiratory protection on hand if gas or ash becomes an issue, and prioritize staying indoors during poor air conditions.

- Know your routes in and out of your area, so you are not improvising during a tense moment.

- Treat “quiet” as a reason to prepare, not a reason to ignore updates.

On the science side, the plan is straightforward: combine satellite watching with ground-based instruments and updated hazard mapping, so small changes are caught early and explained faster. Boring monitoring is the goal, because surprises are the expensive kind of excitement.