A quarter-century-old question about the largest magnetic fields in the universe has grabbed everyone’s attention. Scientists report that these puzzling fields develop around dead stars in a way that was only speculated until now.

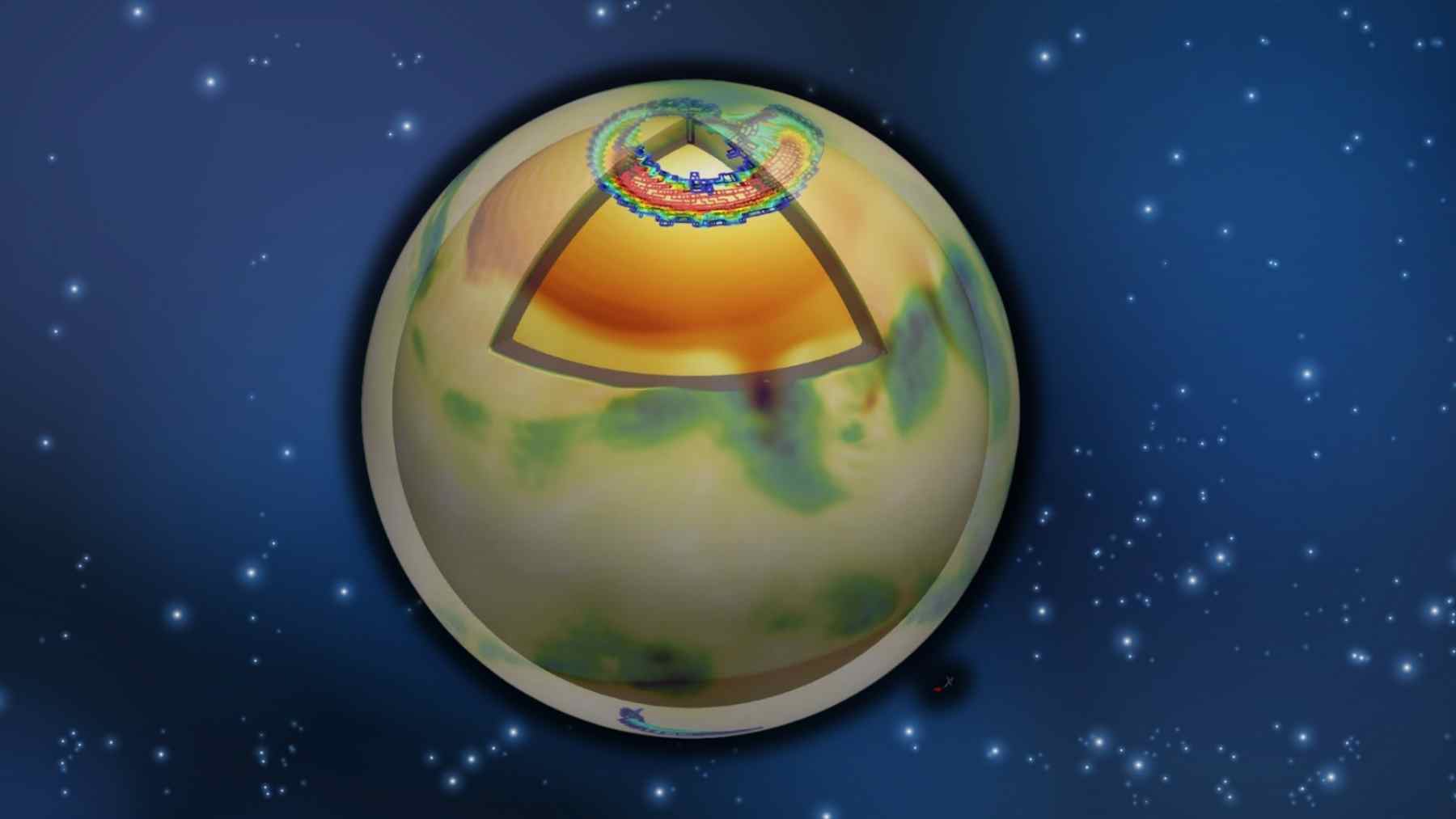

According to Dr. Andrey Igoshev, lead researcher from the University of Leeds, their new simulations have settled debates that have lingered for 25 years. The team’s focus was on the birth and growth of a neutron star, which is a compact stellar core that can remain after a massive star collapses.

Why magnetars catch our attention

A magnetar is a neutron star with a magnetic field that can reach billions of times the strength of what we experience on Earth. Such wild conditions are known to cause bursts of X-ray radiation that defy simple explanations, leading astronomers to look for any clue they can find to explain how these bizarre objects stay so active.

Some magnetars display dipole fields in a lower range, yet they still show the same dramatic flares. That raised an important question about why so-called low-intensity magnetars share striking similarities with those having stronger dipole fields.

How supernova fallout speeds up the star

When a massive star runs out of fuel, it collapses and ejects material outward, leaving behind a tiny, rotating core. A fraction of that matter returns in a process called fallback, and this incoming mass spins the star faster than researchers once expected.

The group found that this faster spin plays a serious role in ramping up hidden magnetic structures. That realization connects a supernova’s aftereffects with a star’s later behavior, solving long-standing questions about the timing of field generation.

Inside the Tayler-Spruit puzzle

A mechanism called the Tayler-Spruit dynamo involves differential rotation that triggers magnetic instabilities inside the hot, dense interior. It was originally proposed years ago, but it had never been fully confirmed as the driver behind certain field configurations.

“low-intensity magnetars can be produced as a result of a Tayler-Spruit dynamo inside a neutron protostar,” wrote Dr. Igoshev, in the published study. His words point to a distinct route for generating big magnetic fields in stars that do not exhibit the classic ultra-strong external dipole signals.

The striking power of low-intensity stars

“X-ray observations show that in two cases, low-intensity magnetars have small-scale magnetic fields 10-100 times stronger than their dipole fields,” added Dr. Igoshev. Observations reveal that certain neutron stars still release bursts just like their mightier relatives.

Objects such as SGR 0418+5729 and Swift J1882.3-1606 confirm that an external reading of the star’s field doesn’t always match its internal reality. The high-energy flashes seen from these objects underscore how less obvious fields can still unleash surprising events.

Where it leads future research

Researchers believe these findings add context to models of supernova remnants and the huge outbursts that neutron stars sometimes display. The role of proto-neutron-star dynamos goes beyond standard theories, linking fallback conditions to later phenomena that defy easy explanations.

This approach might also clarify the huge release of energy in certain gamma-ray bursts. Each step forward reveals ways in which intense fields appear or linger, even after a star has seemingly settled down.

Gazing into the future

Fresh data from upcoming observatories may confirm how these deep magnetic networks form and fuel energetic behavior. The better we map a star’s core, the closer we get to predicting which ones are likely to unleash major flares.

It’s a reminder that conditions right after a supernova can decide what we see billions of miles away. Astonishing details can hide in a star’s interior, prompting us to rethink what cosmic extremes really look like.

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.